This piece appeared originally on the Lepanto Review, the blog of the Chesterton Academy of Our Lady of Victory.

As a father of six, I know it’s hard to balance family priorities. Attending to everyone’s needs—emotionally, spirituality, materially, and socially—while managing the demands of family life, school, extracurricular activities, and work definitely takes its toll! It’s hard to stay focused on what matters most—getting our kids to heaven. Education forms a big part of parents’ strategy, though it takes navigating finances, prospects of future success, and religious formation. How do we pick the right school?

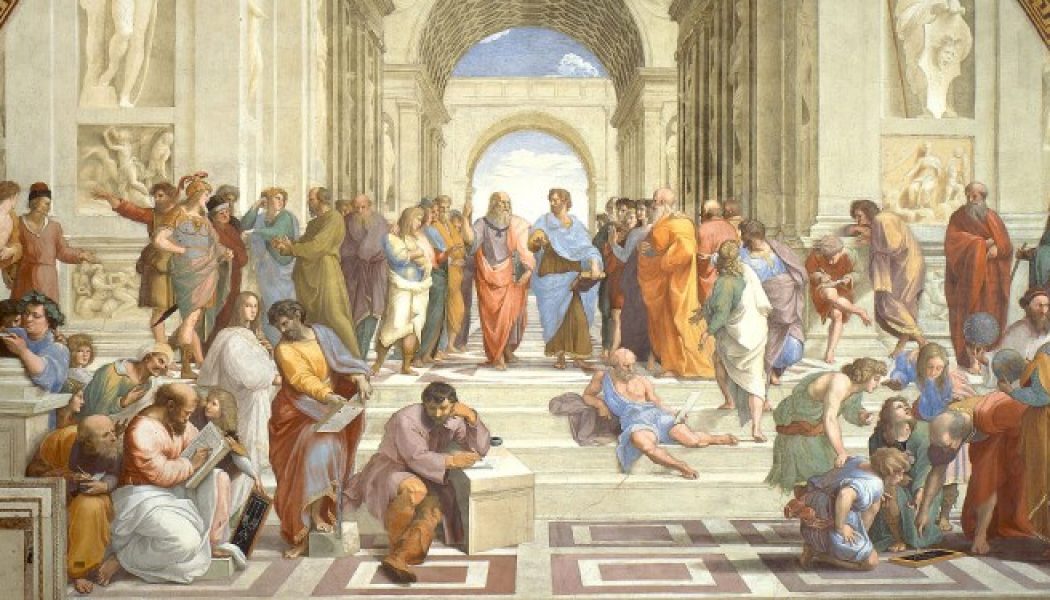

In my mind, deciding on a school requires an understanding of the purpose of education itself. Aristotle begins the Nicomachean Ethics by stating that to understand anything we need to know its purpose: “Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good.” What is the good sought by education? Without answering that question it’s hard to make judgments about the worth or quality of any educational program. If we don’t know the goal, how can we make a good choice?

Catholics in the United States have founded the largest private school system in the world. They did so, interestingly enough, because the public schools originally sought to push a Protestant vision of education. It was only in the twentieth century that public schools took on a secularist agenda, focusing more on the utilitarian function of education rather than its inner, formative power. This new secular bent sought to engineer social change. One recent study by Lyman Stone has noted that “the decline in religiosity in America is not the product of a natural change in preferences, but an engineered outcome of clearly identifiable policy choices in the past.” Public education spearheaded this decline, because, over the past few decades, youth “spent much of their life in schools that were far more secularized, and these are the generations during which religiosity has declined.”

The classical education movement arose to counteract this social change, looking back to the great Christian tradition of education. Although the Catholic Church created classical education in the Middle Ages, the modern classical movement began in the Protestant world, inspired by Dorothy Sayers’s “The Lost Tools of Learning,” and grew to influence the homeschooling movement as well. Inspired by its success, classical education was taken up by charter schools, leaving the Christian tradition behind while continuing to focus on the trivium and quadrivium, as well as classical languages and literature. Ironically, most Catholic schools have been slow to consider a return to classical methods, though this has changed as Catholics have discovered its popularity, Catholic pedigree, and demonstrable success over modern, mainstream models.

With a range of classical options, particularly tuition-free charter schools, however, many wonder why we need Catholic schools at all. Catholic education requires sacrifice and, with more alternatives available, we have to ask, is it worth it?

This is where we need Aristotle’s help again as he prods us to consider the purpose of education. Until recently, the goal had always been identified as the formation of the person, initiation into a culture, and preparation for service in society. Education focused first on becoming someone and only after on doing things. Aristotle, quoting his own teacher, points to the end of education as an interior reality: “We ought to have been brought up in a particular way from our very youth, as Plato says, so as both to delight in and to be pained by the things that we ought; for this is the right education.” It’s not about utility but creating the right sensibility and refinement of desire: learning what is most worthwhile in life and conforming to it.

In fact, education should lead us toward the true goal of life, our happiness, found in obtaining what is most worthy. Aristotle also points to this highest good: “Happiness seems, however, even if it is not god-sent but comes as a result of virtue and some process of learning or training, to be among the most godlike things; for that which is the prize and end of virtue seems to be the best thing in the world, and something godlike and blessed.” Only Christian education can accomplish what Aristotle prescribes—leading students to the ultimate good—while an avowedly secular education cannot.

Education misses the mark if it leaves out what is most important. Once again, Aristotle shows us how “pleasure, wealth, and honor,” or even intellectual excellence, probably a more common motive, cannot constitute our true happiness, because rather than giving us ultimate fulfillment, “we pursue these also for the sake of something else.” An education that focuses on these secondary goods teaches a way of life that will not lead to lasting happiness. How could we tell our children on Sunday that God is most important and then have them spend the largest block of their waking time in a system that deliberately excludes Him? Within a secular education, our children are implicitly taught to think and live for these intermediate goals, making of them something absolute. The skills and facts that are imparted cannot reach their real purpose of supporting the meaning of our existence.

Talking to friends who teach in classical charter schools, they all describe having to “stop short” in their teaching, introducing great thinkers and ideas but not being able to fully impart their meaning. It is absolutely true that classical charter schools are preferable to standard public education, but “stopping short” cannot give young people the full picture of what it means to be a human being and how to live a fulfilled life. Furthermore, it’s not possible to present the Western tradition without imparting an understanding of the Christian vision that preserved classical learning and transmitted it to Europe and the New World. It’s only in the Christian tradition that notions of human dignity, freedom, and happiness reached their full meaning. Seeking to form good citizens, as many charter schools state their aim, without the force that built Western civilization, leaves a huge, moral hole in the curriculum.

Many parents say that they will supplement a secular education with religious formation at home and church. That is good, of course, but it falls into the latent secularism of charter schools by separating education from the goal of true happiness and the deepest formation of the person. The family shouldn’t be working to counteract the school environment, as there should be a partnership between them. Parents say, “I can add faith in myself,” but faith cannot exist as an add-on, even if made an important one. It is the organizing principle of the whole of life and guides everything we do to its goal. To make faith supplemental does not show its primary importance and will make it more likely to continue as an add-on in the future. In a secular environment, students have to conduct learning and live “as if God does not exist,” as Pope Benedict XVI defined secularism, a sort of practical atheism.

Catholic education seeks to impart an education for life, one that integrates the wisdom of the great tradition with personal formation: not only talking about virtue but forming it through a life of discipleship. Students have to learn how to live as Christians in the world, integrating the intellectual, moral, spiritual, and social life into a coherent whole. Catholic schools form good citizens, but also draw students into the City of God, which will last when this world collapses (sooner or later). Classical education finds its deepest expression in the Church, the institution that preserved classical learning after the fall of Rome, that built the first universities, inspired the greatest art, and also formed saintly scholars, like St. Thomas Aquinas.

Education is one of the most important things we can give our children. We can’t settle for second-best for them or give them a partial expression of what they need. We want to teach them how to be truly happy and how to integrate all aspects of their life through faith; to be successful, but, more importantly, to be holy. By integrating faith and reason in Catholic, classical education, we impart the full vision of reality, uniting the formation of mind and soul. Only this will form the basis of true happiness—not only the goal of education, but of life itself.

We can end where we began, with the Philosopher, Aristotle: “And so the man who has been educated in a subject is a good judge of that subject, and the man who has received an all-round education is a good judge in general.” And to him, we can add the Apostle: “Do you not know that the saints will judge the world? . . . Do you not know that we are to judge angels?” (1 Cor 6:2-3). Let’s prepare our children to fulfill the supernatural vocation God intends for them.