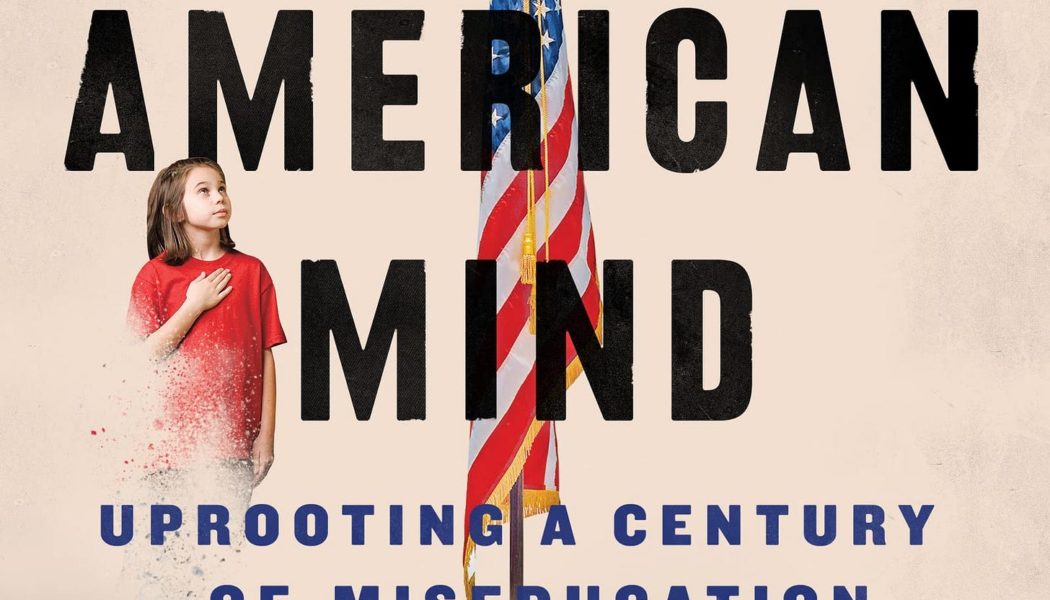

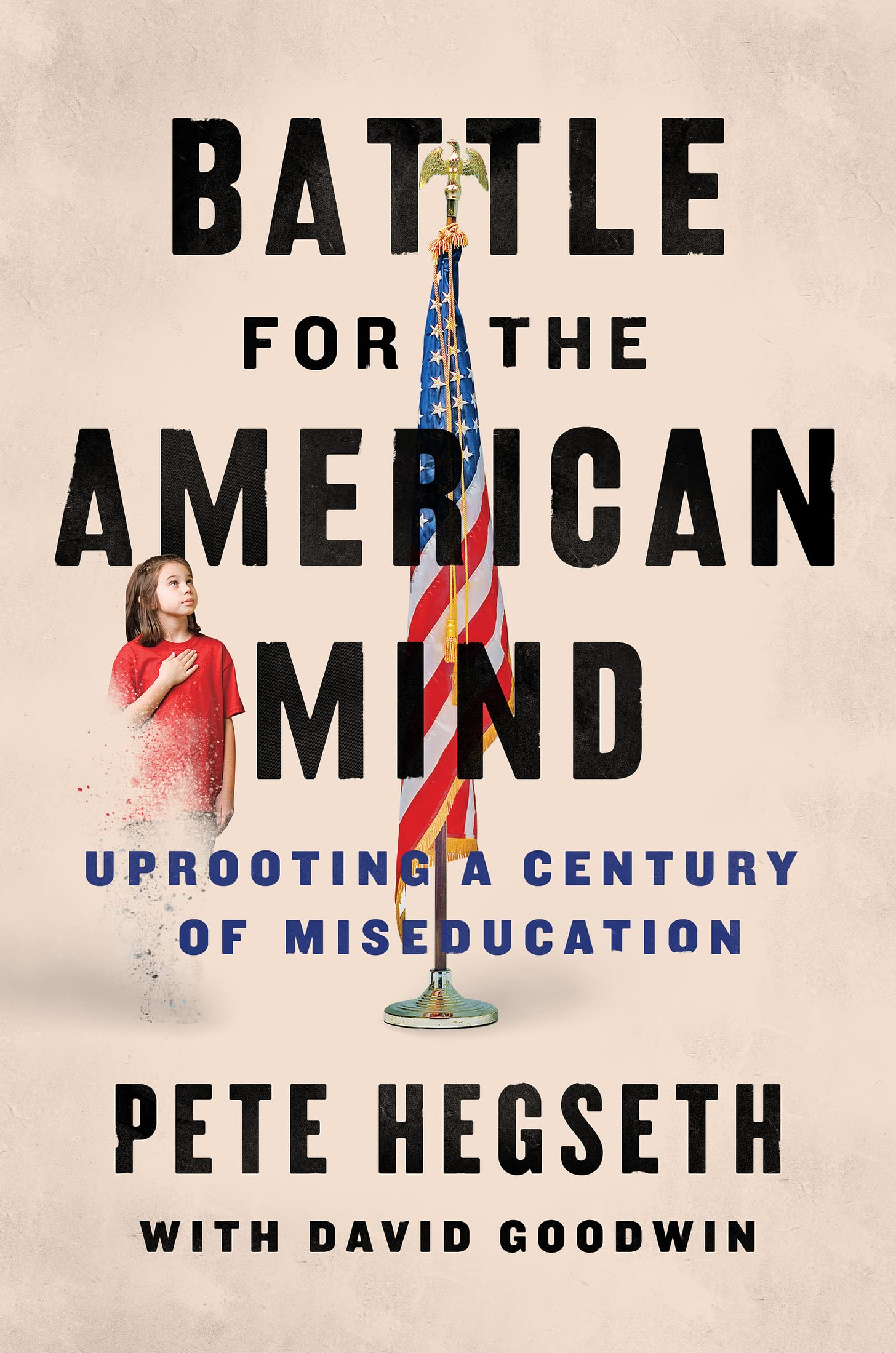

Hegseth, Pete, and David Goodwin. Battle for the American Mind: Uprooting a Century of Miseducation. Broadside Books, 2022.

Battle for the American Mind is, as the title suggests, a polemic. It is not a scholarly work, and it is not the work of academics. As a sort of academic myself, I know that academics often get the details right through painstaking efforts of erudition, but fail to tell a true or honest story about the whole. Modern academic disciplines make little effort and see no need to cultivate the ordinary and human love of the good or the beautiful, let alone to justify their work for prudent laymen, or to submit to the deliberations and judgment of decent and reasonable citizens. This book is in every way the opposite. It is clumsily executed, wildly inaccurate in many details, and lacking a consistent or coherent argument. Yet the story it tells is true and needful, and it is submitted humbly for the benefit of the American people. And it is a story the American people need to hear.

The primary author, Pete Hegseth, is a television host who, by his own admission, “write[s] like [he] speak[s], and has “read next to nothing” of the canonical texts of the Western tradition, despite holding degrees from Princeton and Harvard. David Goodwin, his co-author, was an early classical school pioneer and is now President of the Association of Classical Christian Schools, which represents more than 300 such schools around the United States. Together they paint a bleak picture. American education, once both Christian and classical, has been thoroughly transformed by a godless progressivism. This happened not in recent years through our suicidal obsessions with race and gender, or in the 60’s and 70’s with cultural Marxism or critical theory, but more than a century ago, with progressivism. This transformation was actually supported and furthered by the mainstream of America, even though it was designed, from the beginning, to root Christianity and the Western tradition out of their schools.

Insofar as there even was a “battle for the American mind,” it was lost a long time ago. We traded a rich, life-giving inheritance, the education of a free people, for trinkets like skills- and jobs-training and the Pledge of Allegiance. Conservatives lost so badly that they now clamor for these progressive innovations as the wholesome, old-fashioned education we need to get back to. The entire lexicon of the debate has been established by their enemies, and their children spend, as the authors often repeat, 16,000 hours a year in schools which turn them against their faith, their tradition, their country, even their own bodies.

What was our inheritance? The “Western Christian Paideia.” This is WCP for short, and the authors need the acronym, for they use the term a lot, packing everything they like into it: Judaism, Greece, Rome, Christianity, the medieval liberal arts, and the American Founding. This is alternately called a “weapon,” an “ingredient,” a “power,” even a “vaccine,” and the adjectives “secret” or “magical” might as well have been appended for all that is attributed to this chimera—it is the one easy trick ‘they’ don’t want you to know about. You’re going to be shocked! “Turn the page” to find out more!

As unsophisticated and distasteful as this simplistic amalgamation is, it’s sort of right. Classical culture was taken up by Christianity and has informed the West’s self-understanding for two millennia. This includes America, which used to see itself within this tradition, even as a New Jerusalem, or a new and better Roman republic, and was sometimes itself unlearned and unsophisticated in this representation. The basic task of American education was to pass on this tradition, and in the best case to make citizens who understood their rights and duties, able to deliberate in common with prudence and justice. Its task was not to create a new type of man, unmoored from the prejudices of the past, or to train a modern workforce, the collaborative, patriotic slave-subjects of the new regime, ruled by scientifically-trained administrators. This, the “American Progressive Paideia” (APP) is what your betters have seen fit for you to receive. This is why your schools are garbage.

The book is best in its telling, in outline, of this story. As for the details, it is most interesting in recounting how religious movements in America, both within evangelicalism and mainline Protestantism, made the progressive takeover of education possible, and then, once this was effected, how the establishment of private Christian schools actually further entrenched the APP. When the progressives finally showed their anti-Christian cards, Christians fell back on the progressive education they knew, not realizing that this was already an attempted displacement of their Christian faith and the moral and intellectual tradition informing it. This book is for those Christians who are the heirs of this bait-and-switch, and cries out, like a prophet in the wilderness, for them to return to the WCP and CCE (“Classical Christian Education”) of their ancestors.

Battle for the American Mind gets many other things wrong. Despite its attempt, even regular promise to distinguish them, it regularly conflates Marxism and progressivism, even as it admits that the former was explicitly atheistic and the latter had many sincere Christian adherents. But both are enemies of WCP, which is otherwise represented as an unbroken tradition. There is nothing here about modernity, liberalism, German idealism, or the effects of the German research university model on K-12 education. Further, what is here of the American Founding and earlier historical and intellectual moments is unreliable. In the founding era, according to the authors, “nearly every citizen was educated classically.” Given how nebulous their definition of WCP is, this is hard to refute. But the context of this statement is a defense of the teaching of Latin. By the middle of the 19th century in America, barely over half of school-age children were actually in school, let alone learning Latin. Yes, those who did go to school used classically-sourced readers, read the Bible, and were generally formed by the tradition rather than shaped by antagonism towards it. But is this the same thing as classical education?

Going back to the beginning, the authors write that paideia is “a power discovered by the Greeks.” This (to which they add, “and called out in the Bible”) is the thesis of Werner Jaeger’s famous treatment by this name: the Greeks invented deliberate inculturation. But it’s not true that “the Greeks… sought to align humans with God (the Logos)” or that they “built a civilization” on the “idea that man has a special type of connection to the metaphysical.” Or that paideia was “created for a self-governing people” and was “the innovation of a classical world dedicated to freedom and freedom-loving people.” It is not necessary thus to conflate Christianity with classical learning, and both with American republicanism.

Nor must we fail to distinguish the virtues and actions which make political order, and the education and religion which sustain them. Of course these overlap, and are related. But they are not “fused into a singularity,” and we have no right to read Plato and the Gospel back into the origins of Greek cities, nor to pretend that early American education was a fulfillment of Greek philosophy and Christian religion. Americans have always been a practical people, with little time for speculation. Reformers found fertile ground here for object-based learning, laboratory classrooms, and other illiberal, anti-classical innovations in education. Hegseth and Goodwin do well to expose the anti-Christian goals of Dewey and his successors, but these trends started well before them. Case in point: the Oswego Movement, which started training American teachers in distinctly unclassical methods as early as 1861.

As the authors rightly note, it’s the methods that matter, not whether you can include the Bible or have religion classes. You can be reverent of and receptive to the tradition, focusing on the good of our common inheritance, and form the student by this light, or you can turn the student inward, make the education reflect his own ill-formed passions, and serve the prejudices and dimly-perceived needs of his own time. Classical education does the former, progressive education does the latter. In a certain way, this book tells Christian parents: stop focusing so much on whether the school says it’s Christian, and focus on whether it’s progressive or classical. And yet, it also proclaims, “Charter schools cannot truly do classical education because they can teach nothing of transcendent truth, biblical revelation, or God, not to mention the truth system of Christianity.” Without Christianity, “we cannot truly understand anything.”

There can be no more anti-classical sentiment than this, and until conservative Christians are cured of this intellectual affliction, they can never have a workable battle plan for winning back education. This is not to say that our schools should not be Christian. They should. Our public schools, too, should not prohibit Christian expression, and certainly not the teaching of the works of the Christian tradition (including the Bible, which I myself taught, as true, in a public charter school). But the idea that truth cannot be known without Christian revelation is fideism, which is antithetical to the classical tradition, and what’s more, to the Christian intellectual tradition. Most truth can be known through natural reason, independent of God’s revelation, and we need not always find confirmation in Scripture to know that something is true. This is surely not what Paul means by “take every thought captive.” This is not Quintilian but Tertullian, who asked, rhetorically, “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens?” No just principle prevents Christian truth from being taught in American public and charter schools, but independently, no just principle prevents them from having a classical paideia, either.

These flaws—flaws which are characteristically American—aside, the book’s account of APP is good and needed. We are now, of course, in the age of APP’s successor, the “Cultural Marxist Paideia.” This is mostly a distraction from the main story, a horrifying carnival spectacle to gawk at and revile. This is not to downplay its great, dehumanizing horrors. But as we proceed deeper into this insane abyss of cultural, spiritual, and physical self-mutilation, it becomes harder to see what we have lost, and what brought us here. This book, clumsily but successfully, tells what happened, and how we can begin to fight again.

John M. Peterson is Assistant Dean, Graduate Director of American Studies, and Sub-Director of Classical Education in the Braniff School of Liberal Arts at the University of Dallas. He tweets @thejohnpeterson

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity