The Holocaust Museum at Auschwitz includes exhibitions documenting the Shoah in various countries. In the Dutch pavilion there is searchable computer database for those murdered at Auschwitz by the Nazis.

If “Stein” is entered, the following information is displayed:

Family Name: Stein

First Name: Edith Teresia Hedwig

Date and Place of Birth: 12-10-1891 Breslau

Date and Place of Death: 9-8-1942 Auschwitz

There is a similar entry for Edith’s sister, Rosa. The two Jewish converts to Catholicism, both Carmelite nuns, were deported from the Netherlands on Aug. 7, 1942, and killed in the gas chambers at Auschwitz on Aug. 9, 1942.

Behind those simple dates lies a great tale of the conflict between the Catholic Church and the Nazi regime.

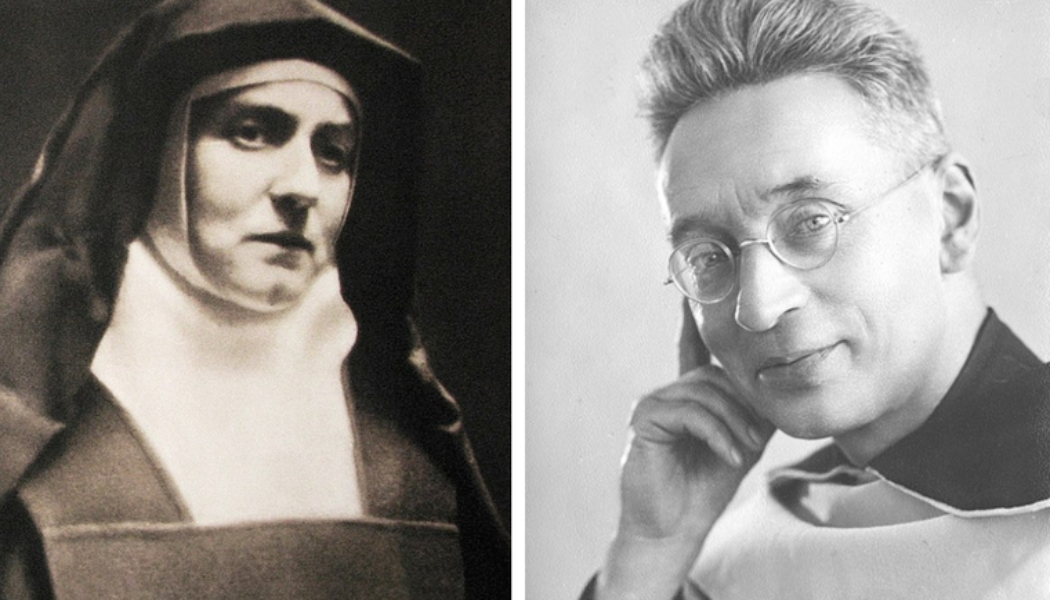

The 80th anniversary of the martyrdom of St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) — canonized in 1998 and declared by St. John Paul II a co-patroness of Europe — is a reminder of the drama of the summer of 1942. Just a few weeks before Teresa was martyred at Auschwitz, Titus Brandsma, canonized just this past May, was killed at the Dachau concentration camp by lethal injection in the camp “infirmary”.

In 1942, the Nazis were intensifying their murderous campaigns against Jews and political resisters. St. Titus was a leader of the resistance efforts that led indirectly to the martyrdom of St. Teresa.

Edith Stein, raised a Jew but turned an atheist in her teenage years, decided to become Catholic after the brilliant philosopher read the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila. Baptized 100 years ago, on Jan. 1, 1922, she would eventually become a Carmelite, following the path of Teresa of Avila. Eventually, Edith’s sister Rosa would follow that same path, too.

Edith was baptized in Breslau, then part of Germany, now Wrocław, in Poland. She joined the Carmelites there. As the Nazis took power and persecution of Jews increased, it was decided that it would be safer to send the Stein sisters, Jewish by birth, to a Carmelite house in the Netherlands.

Titus Brandsma, also a Carmelite, was one of the most prominent Dutch priests. Unusually for a Carmelite, Brandsma had a very active apostolate in both Catholic higher education and journalism. He was an outspoken critic of Nazism.

In 1941, the Dutch bishops made a strong denunciation of the Nazi regime occupying their country. In response, the Nazis decreed that Catholic newspapers must print pro-Nazi advertisements and press statements. Father Brandsma, well known by the country’s small episcopate, encouraged them to stand firm. In turn, he was asked to carry secret letters from the bishops to the editors of Catholic newspapers, instructing them not to reprint Nazi propaganda.

Father Brandsma accepted the mission. He knew that it imperiled his life. He managed to visit 14 newspaper editors before he was arrested in January 1942. He would eventually be transferred to Dachau, near Munich, which housed thousands of priests. He was tortured and savagely beaten. He was killed on July 26, 1942.

The witness Father Brandsma had offered while still in the Netherlands had encouraged the Dutch bishops, even as they had, in turn, strengthened him.

As the Nazis began mass deportations of Dutch Jews to the camps in July 1942, the Dutch bishops, in union with the other Christian churches, sent a telegram to the Nazi authorities, condemning the deportations. In response, the Nazis agreed that they would not deport Jews who had become Christian before January 1941. Yet if the protest was made public, Jewish converts to Christianity would also be deported to the death camps.

The other Christian churches thus demurred from making their protest public. The Dutch Catholic bishops, however, wrote a strong pastoral letter condemning the deportations, dated July 20, 1942. It was read from all the pulpits in the country on Sunday, July 26, 1942 — the same day Father Brandsma was murdered in Dachau.

The consequences were swift and harsh. Far from ceasing their deportations of Jews, the Nazis began deporting Jewish converts to Christianity, too. Fifteen days later, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross would be dead at Auschwitz.

When the Gestapo came for the Stein sisters at their Dutch Carmel, Edith, ever a daughter of Israel, said to her sister Rosa, “Come, let us die for our people.”

Pope Pius XII was deeply shaken by the response to the Dutch pastoral letter and conducted his opposition to the Holocaust accordingly. With great practical creativity and urgency, Catholic institutions were essential to saving the vast majority of Roman Jews. Yet after the Dutch experience, Pius refrained from an open and direct condemnation of the Holocaust. Though he spoke with more clarity than Roosevelt or Churchill or any other Allied leader, his diplomatic efforts are the subject of controversy even to this day.

There is a Polish complement to the Dutch drama.

On Aug. 14, 1942 — the first anniversary of the martyrdom of St. Maximilian Kolbe at Auschwitz — a Vatican emissary arrived in Kraków to see the indomitable Prince-Archbishop Adam Sapieha, the hero of the “long night” of Nazi occupation. Archbishop Sapieha, who was then operating a clandestine seminary out of his residence that included Karol Wojtyła — was a fierce resister of the Nazis.

With documents from the Holy Father camouflaged with spaghetti labels and hidden in wine bottles, the emissaries avoided detection of their clandestine papers by the Gestapo. They had brought to Archbishop Sapieha a letter to the Polish Church from Pius XII entitled, “Ideological Differences and Opposition to National Socialism.”

Archbishop Sapieha read it in horror. Papal solidarity was welcome, but he knew the consequences of public denunciation.

“It is absolutely impossible for me to share [it] with my clergy, and much less can I communicate it to the people of Poland. It would be sufficient for only one copy to reach the hand of the [Nazi intelligence] and all our heads would fall,” Archbishop Sapieha explained to his visitors.

“In this case, the Church in Poland would be lost.”

Archbishop Sapieha immediately burned the package.

The Polish shepherd may have already heard about the reprisals against the Dutch pastoral letter. He likely did not know that Teresa Benedicta of the Cross had been killed only five days earlier in his own archdiocese. He likely did not know that Titus Brandsma had been killed 19 days earlier in Dachau, though it is possible that he knew the priest had been interned for encouraging Catholic institutions to resist the Nazis.

In any case, Archbishop Sapieha knew well the pressures of the Polish occupation. He would not have known that his seminarian Wojytła would become pope, but he likely feared that Wojtyła and others would have been killed had he circulated the papal condemnation.

Pius XII evidently understood. Within a year of the war’s end, he created Archbishop Sapieha a cardinal.

The lessons of August 1942 are complex. Courage and prudence in the face of evil are lessons to be learned anew in every age.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity