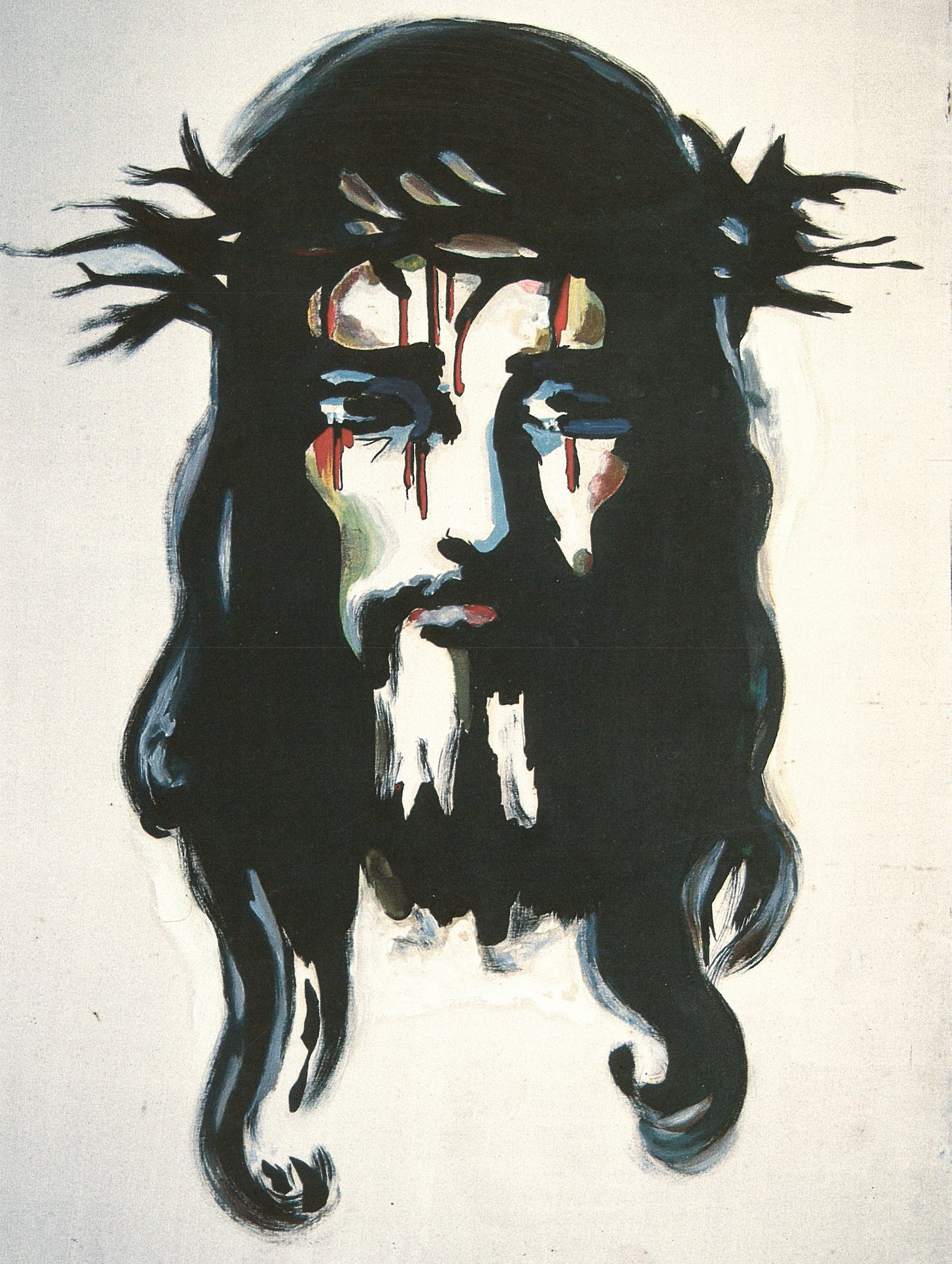

A while back, I listened to an episode of The Daughters’ Project about the importance of not erasing the saints’ struggles from their stories, and it got me thinking about Rafael’s. As the sisters point out, hagiography that totally glosses over the sins that saints struggled with, or casts the suffering they went through in a rosy, transcendent light, doesn’t do anybody any good. The whole point of saints is that they were human. The whole point of saints is that you can and should become one. And nobody’s going to believe they can become a bilocating stigmatic who never had a sour thought or word for anyone.

But what about a sad, struggling kid?

That podcast episode made me think about a story buried in the footnotes of the Spanish edition of Saint Rafael’s writings, quoting from the abundant material associated with his canonization process. It’s from an interview with Brother Domingo García Hidalgo, who was once the brother in charge of the infirmary at the Monastery of San Isidro de Dueñas. He remembered this night in late 1936 when his heart absolutely broke.

Let me set the scene for you. The Spanish Civil War had just broken out, and all able-bodied men of military age were conscripted into the national army. Monks in formation were not exempt. As we now know, but he had not yet fully come to terms with, Rafael was not able-bodied. Diabetes was ravaging him. Everyone who knew him could tell he wasn’t well. And even so, he reported for duty, hopeful. Then he was found unfit and sent home, utterly dejected.

Rafael felt so useless and alone, being sent back to the monastery that had been emptied of its other young men. And how could he not? I always have to remind myself that the Spanish Civil War didn’t feel like a Wikipedia article, the pros and cons all laid out, the factions clear, the stakes crystal. All he knew about the conflict was that some people he was told were communists had surrounded his monastery and tried to kill him and his brothers. His seminarian friends back in Oviedo were shot in the street. That is the information he was working with. He couldn’t do anything, materially, to help them. His body was failing him as a citizen, as a friend, as a man.

So in late 1936, Rafael isn’t just alone among his friends and family as a man not fighting. He isn’t just alone in the monastery without any other novices or oblates or monks in formation. He’s also alone in the infirmary, too weak to participate in community. He was despondent.

It probably didn’t help that poor Brother Domingo wasn’t prepared for his job as infirmarian. Normally, a brother with medical expertise would be assigned to head up the infirmary and take care of the sick and elderly brothers in need. But the infirmarians had been conscripted with everyone else. Brother Domingo stepped up, but he had no idea what he was doing. And unfortunately, Rafael wasn’t the type of patient who would actually tell you if he was in pain or starving or thirsty or slowly dying, which he was. He’d just take it.

But they could pray together, at least. Every night, Rafael and Domingo would go to the infirmary chapel and make a “holy half hour” before going to sleep. It wasn’t the big monastic community Rafael thought he’d signed on for, but it was something.

One night, though, Rafael didn’t show up, and Domingo went looking for him. He found him in bed, sobbing uncontrollably. When Domingo asked him why he hadn’t come to chapel, Rafael said, “Jesus and Mary don’t want me there. A voice told me to go back to bed and never come back. I’m useless, an abomination in God’s eyes.”

Useless. That word was killing Rafael. He was delirious from the pain, and clearly under spiritual attack and having a mental health crisis to boot. In his right mind, he knew Jesus and Mary wanted him by their side, always. He knew he was never really separated from them. But in this moment, the uselessness made him feel utterly alone, too alone to move.

I thought about this story when I heard the sisters’ podcast because it illustrates so perfectly that the saints’ lives are not about human perfection and flourishing and rosy health, but God acting in our messiness and loving us all the way through. With the distance of history and geography, of course I can read that story and see God’s mercy in keeping him home from the war. Rafael was saved from serving a cause that went nowhere good. His own cousin was out there committing literal war crimes. There but for the grace of God, part of me thinks. Sure, our saint was never much one for ideology, but violence can change people. You never know.

So of course I can see God’s loving kindness at work in keeping him away from it all, preserving his pure heart, asking him to serve on a far more righteous front. But Rafael didn’t know any of that. All he knew is that he was alone in the world while it was falling apart.

And he is no less a saint for having had that crisis. His life was never sunny, exactly, but he got through it. He found meaning. He had a holy death. He beholds the eternal God as we speak. So if that’s you—“God doesn’t want me, I’m useless, an abomination”—know that a saint is among you. This feeling is not forever, and you are not alone.

If you have had thoughts like Rafael’s and are struggling, there are crisis hotlines and text lines that can help. If you’re not in immediate crisis, but do want to have more conversations about Catholicism and mental health, I recommend the Saint Dymphna’s Playbook podcast (and forthcoming book). Know that St. Rafael is praying for you.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity