Sir, the only method by which religious truth can be established is by martyrdom.

—Samuel Johnson

Christian marriage has always been a challenging ideal, but until recently there was a broad consensus as to its constituent elements. When England’s Henry VIII, for example, decided in the 1520s that he wanted to marry Anne Boleyn, he knew he’d first have to free himself from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Everyone, including the King, took it for granted that marriage was monogamous and permanent — and technically (despite frequent royal breaches) exclusive. In other words, marrying Catherine while still married to Anne simply wasn’t an option for Henry, and attacking the definition of marriage head on would’ve been both foolhardy and futile.

Instead, Henry and his team doubled down on rationalizing his nuptial irregularities. They sought to overrule papal denunciations by buttressing the King’s claims that his divorce and remarriage was consistent with biblical norms. Political and ecclesial upheaval followed, and 16th-century England was thrown into a violent turmoil that lasted generations. Nevertheless, even amid social and ecclesial meltdown — including severe persecutions and countless martyrdoms — the basic understanding of what constituted marriage remained fundamentally intact.

Times have changed. These days, that broad social consensus regarding marriage is in free fall.

Take unity and indissolubility, for instance — the two “essential properties of marriage” (Canon 1056) that gave Henry VIII so much trouble. He’d have no such trouble today, for divorce is a commonplace, and serial marriage, routine. Marriage as a lifelong, come-what-may commitment is by and large an alien notion — even in the Church. Pope Francis said as much in controversial remarks last month about our age’s culture of impermanence and the questionable validity of so many modern marriages. “They say ‘yes, for the rest of my life!’ but they don’t know what they are saying,” Pope Francis commented. “Because they have a different culture. They say it, they have good will, but they don’t know.”

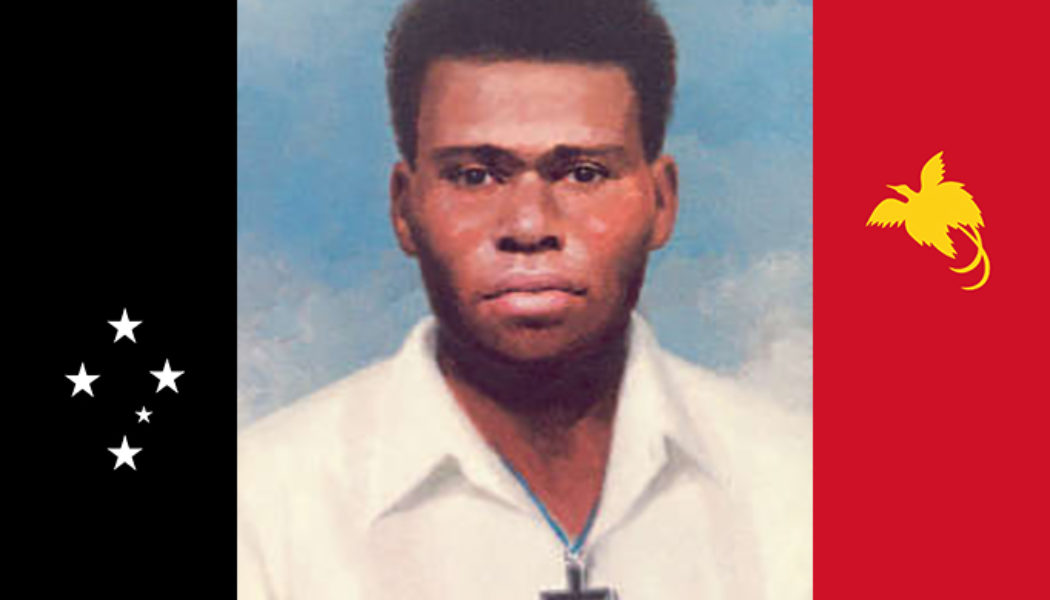

For this reason, Papua New Guinea’s Blessed Peter To Rot is an especially important role model for our times, and it’s part of the reason he was chosen as a patron of Sydney’s World Youth Day in 2008.

To Rot was born in 1912, but his story has its roots in the 1870s when Methodist missionaries first introduced Christianity to the island. The Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart arrived shortly thereafter, and they were particularly successful in gaining adherents to the Church, especially among the island’s tribal leaders.

When Angelo To Puia, an influential chieftain, embraced Catholicism and received baptism in 1898, the entire village followed his example, and the ripple effect in neighboring villages meant that a thriving regional Catholic community swiftly took shape. Angelo worked closely with the missionary priests in forming the faith of his people, and that extended to his own family — including his third child, Peter To Rot.

Since missionaries and clergy were scant in the huge Oceania territory, care of New Guinea’s budding local Church largely fell to lay catechists. Blessed Peter was a standout in this regard, and his easygoing piety along with his skills as a teacher propelled him into a position of leadership that transcended his elite blood ties. He was prayerful and devout, and he freely extended himself on behalf of the fledgling Catholic community: catechizing young and old alike, urging them to get to Mass and receive the sacraments, and promoting a joyful lived faith through his own example — something he continued to do after marrying Paula Ia Varpit in 1936. His witness as a dedicated husband and, in time, doting father helped reinforce the eradication of polygamous practices throughout New Guinea that had coincided with Christianity’s widespread adoption.

Then imperial Japan bombed and invaded the island in 1942 — a punishing blow to the New Guinea Church. In order to consolidate control, the Japanese set up prison camps for foreigners, especially priests. Before his internment, one of the Sacred Heart Missionaries beseeched To Rot to take over his work, saying, “Look after these people well. Help them, so that they don’t forget about God.” Despite official prohibitions and great personal risk, To Rot did just that, organizing secret religious meetings, for instance, and even the administration of the sacraments.

When the Japanese realized that the Church of New Guinea wasn’t going to collapse just because the missionaries were removed, they tried a different tack and re-introduced legal polygamy on the island. In so doing, they sought the support of local chieftains who harbored resentment toward Christianity’s absolute monogamous obligations and who would welcome a chance to take a second wife.

Peter, heedless of the dangers, totally rejected these Japanese efforts to undermine Church teaching on marriage. “The Japanese cannot stop us loving God and obeying his laws,” he said. “We must be strong and we must refuse to give in to them.” To Rot strongly defended monogamy among the faithful, and reprimanded those who entered second marriages — including his own brother. After Peter interfered with the bigamist designs of a native Japanese spy, he was denounced to officials and arrested. “I am in prison because of the adulterers and because of the church services,” he told a village chief who paid a visit. “Well, I am ready to die.” He resisted Paula’s entreaties to give up his catechetical apostolate and plead for release so that he could come home to his family. Instead, Peter asked his wife to bring him his catechist’s cross, the emblem of his office, saying, “I must glorify the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and thus help my people.”

Sometime in July 1945, the Japanese authorities killed Blessed Peter by poisoning and a follow-up savage beating. Although prison personnel tried to cover up the incident, word got out and To Rot was immediately acclaimed a martyr — a martyr for the faith in general and for the integrity of Christian marriage in particular.

Which brings us to today — July 7, the feast of Blessed Peter To Rot — and the special relevance of his heroic fortitude to current challenges. We live in a cultural milieu that long ago dispensed with conjugal indissolubility and fidelity, but it is now also defying the more rudimentary understanding of marriage as a union between one woman and one man. Moreover, although contraception has been a marital mainstay for generations, there’s renewed attention given to the Church’s continued prohibition of artificial birth control and her insistence that “each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life” (Humanae Vitae 11). For many, this is just an obscure relic of ancient Catholic lore, but the controversy swirling around federal contraceptive healthcare mandates has focused fresh scrutiny on the teaching.

There’s no question that the legal and cultural landscape with regards to marital love is rapidly shifting away from what remains of traditional perspectives, and so we can be assured that the Church’s uncompromising views will continue to come under fierce attack. May we who are married be equally uncompromising in both living out the Church’s teaching completely and attesting to it in words— just like Blessed Peter To Rot. “Because the Spirit of God dwelt in him, he fearlessly proclaimed the truth about the sanctity of marriage,” said Pope St. John Paul II at the 1995 beatification of To Rot. “He refused to take the ‘easy way’ of moral compromise.”

Neither should we.

This article originally appeared July 7, 2016, at the Register.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity