Peter’s Pence, the annual collection to support the work of the Holy Father, reported an uptick in donations for 2023, but allocated nearly 90% of revenue to Vatican operating expenses.

And although voluntary donations climbed after 2022, total revenue to Peter’s Pence in 2023 nearly halved, after the fund disposed of millions of euros in real estate assets to help cover the operations of the Roman curia the previous year.

While climbing Peter’s Pence donations are getting headlines, the more important story told by the report is an ongoing budget black hole at the center of the Roman curia, with the Vatican’s need for cash absorbing not only donations to Peter’s Pence, but triggering a sale of the fund’s assets as well.

The annual Peter’s Pence collection is taken on the nearest Sunday to the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, June 29, falling this year on June 30. To coincide with the collection, the fund released its annual report for the previous year’s collection and disbursements.

According to the report, in 2023 Peter’s Pence collected 52 million euros in total revenue, 48 million of which came from donations from around the world. Donations rose over 2022, when receipts totalled 43.2 million. However, those headline figures sit over significantly higher expenses for the fund, which also recorded more than 109 million euros in costs and disbursements.

The nearly 55 million euro gap between donation income and grant allocations was bridged, the report said, by just over 3 million in income generated by assets belonging to the fund and by spending millions in cash generated from the 2022 sale of real estate assets, when the fund recorded more than double its 2023 revenue.

The 2022 annual report recorded 63.5 million euros in “financial and other revenue,” in addition to donations totalling 43.5 million, compared to only 3 million of such income in 2023.

The 2022 report noted the extra-donation income was boosted by “a significant capital gain” which came “thanks to the sale of real estate assets assigned to the fund.” The report did not include a final figure for the sale income. However, the 2023 report did identify it subsidized that year’s allocations with 51 million from “the Peter’s Pence Fund patrimony.”

In 2022, Peter’s Pence assigned more than 95 million in grant allocations and disbursements, compared to more than 109 million in 2023.

Allocations for “direct assistance to those most in need,” charitable projects picked by the pope, totaled 13 million euros in 2023, spread across 236 projects in 76 countries. Of the 103 million given out by Peter’s Pence last year, the report says, 90 million (87%) went to funding the operations of the Roman curia.

In 2022, 16.2 million went to charitable projects, versus 77.6 million euros which went to funding Vatican departments.

The figures suggest that, rather than building up and relying on stable assets to generate regular returns, or limiting its grant allocations in line with donations, Peter’s Pence is selling its stable patrimony to plug the Vatican’s budgetary black hole.

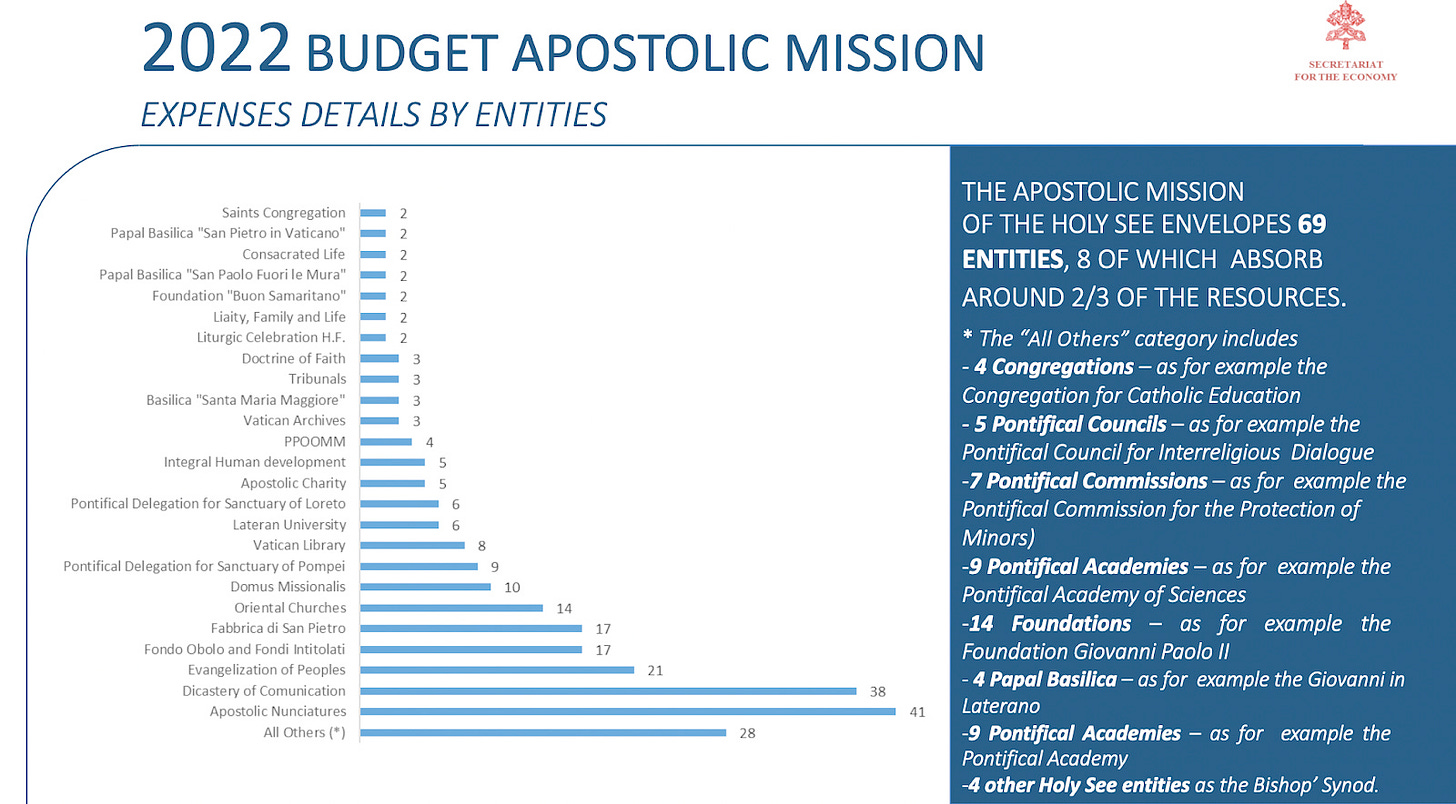

It is unclear what percentage of the annual Vatican operational budget was made up by the 90 million euros it received from Peter’s Pence last year. The Vatican’s Secretariat for the Economy formerly published an annual mission budget presentation, but has not done so since 2022.

According to the last published budget report, curial operations in 2022 were set to cost 796 million euros per year, with a forecast operating loss of 33.4 million after expected donations from sources including Peter’s Pence.

In October 2023, the secretariat’s prefect, Maximino Caballero Ledo gave an indication of the scale of the Vatican’s financial “crisis” when he said that the Holy See had a structural budget deficit of “between 50 and 60 million euros a year,” despite years of cost-cutting measures implemented by the Holy See and a curia wide hiring freeze.

Caballero Ledo was promoted to prefect in 2022, following the resignation of Juan Antonio Guerrero Alves, SJ, for health reasons.

As part of Pope Francis’ efforts to bring financial reforms to the Vatican, a curia-wide pay and hiring freeze has been in place for nearly a decade — though 2021 budget reports show salaries remain the curia’s biggest single expense line at 139.5 million euros, so Francis instituted senior level pay cuts for clerical employees.

Pope Francis has continued to authorize a slew of financial reforms aimed at tightening central oversight of major expenditures and encouraging curial departments to work together to share the costs of external purchasing and contractors.

Early in 2023, Pope Francis announced that he would end the practice of offering subsidized Vatican accommodation to senior curial officials, citing “a context economic crisis such as the current one, which is particularly serious,” which the pope said highlighted “the need for everyone to make an extraordinary sacrifice.”

The pope has also ordered the centralization of all curial assets and accounts under the management of the Institute for Works of Religion, Vatican City’s for-profit bank, including the “on-shoring” to Vatican City of all Holy See funds held in foreign bank accounts — a move portrayed by Vatican financial officials as a bid to stave off a liquidity crisis for the Holy See.

The sale of stable assets by Peter’s Pence to fund daily running costs raises serious questions about the medium-term financial viability of Vatican operations.

In February, a senior official close to the Secretariat for the Economy told The Pillar that “Our Lord guaranteed the Church will never fail, but that guarantee didn’t come with an annuity.”

“There’s no magic money tree in the Vatican gardens,” he said.

“There are still a lot of underperforming assets that need to be identified and maximized,” said the official, “but even that goes only so far. We are talking about very large operating losses every year bleeding away reserves.”

“Everyone likes to cheer the small victories, chipping away here and there at an unsustainable situation, but there’s no big picture thinking. Past a certain point, you’re just trimming the catering budget on the Titanic — sure you’re making savings, but what you need is a total change of course.”

Another senior Vatican financial expert predicted to The Pillar that a curial cash crunch looked increasingly unavoidable in the medium term: “I would say in five years, maybe.”

“People like to imagine the Vatican is ‘too big to fail,’ especially people in the Vatican,” he said. “But if the deficit is totally unsustainable, and shuttering whole departments is unthinkable, what is the plan, exactly? I don’t think there is one.”

Sources close to the Secretariat for the Economy also previously told The Pillarthat in the early years of Francis’ reforming efforts, under the leadership of Cardinal George Pell, the department drew up plans for generating new and more reliable long term income streams for the Holy See by identifying land and buildings otherwise not being used.

Plans included the large-scale development of sites for industrial, residential, or mixed use but would be contingent on securing external partnerships to develop sites and land while signing long-term leasehold agreements stretching out for decades. Such projects would also take years to come online and likely entail significant upfront expenses.

The same sources said that while the potential for new, significant, long term revenue generation was there, curial will outside the Secretariat for the Economy was not.

“The pushback from APSA [the Holy See’s real estate manager], from the Secretariat of State, from people around Number 1 [Pope Francis] was total — it was absolute,” one source recalled to The Pillar. “We were called alarmists, radicals, and so nothing got approved and everything went in a drawer.”

Now, the window for bringing such projects to fruition is closing fast, if it is not already closed.

All sources agreed that a medium-term Vatican liquidity crisis is now at least as likely as not. “When that happens,” the Secretariat for the Economy official said, “options are limited and very bad things can start happening.”

In October last year, secretariat prefect Maximino Caballero Ledo noted that “If we were to cover this deficit [in curial operating expenses] only by cutting expenses, we would close 43 of the 53 entities that belong to the Roman Curia, and this is not possible.”

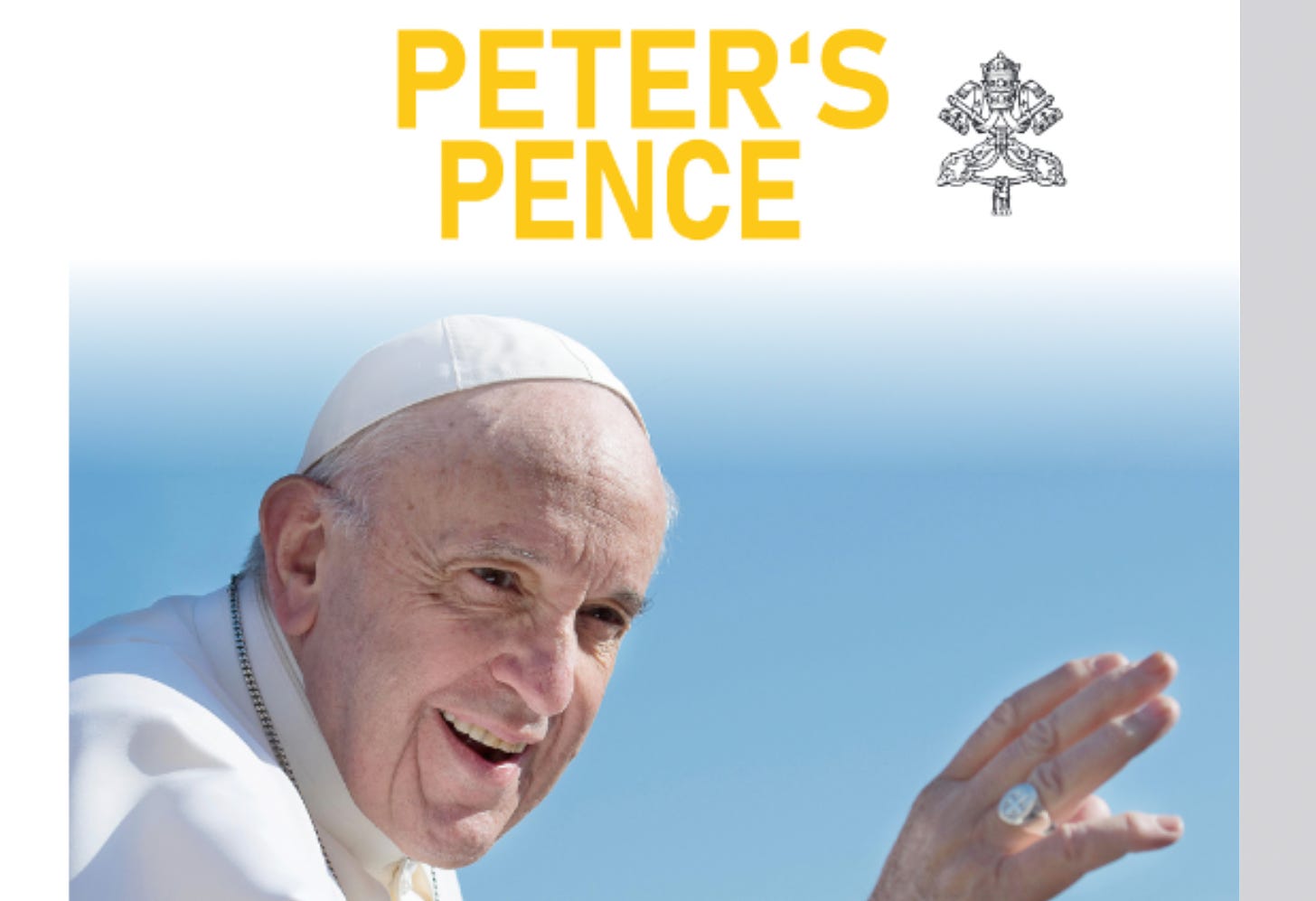

That comment shed partial light on the relative costs of Vatican departmental operations. According to 2022 budget figures — the last year such numbers were published — 56 smaller Vatican departments split a total operating budget of 28 million euros.

Other key dicasteries of the Holy See, including the Dicasteries for the Doctrine of the Faith, and for Laity, Family and Life, operated on budgets of 2 million euros each.

The Holy See’s global diplomatic network of papal embassies was the most expensive department, costing some 41 million euros per year, followed closely by the Dicastery for Communications, with an annual budget of 38 million euros.

By comparison, the Dicastery for the Evangelization of Peoples, the Vatican’s missionary and evangelizing department, was budgeted only 21 million.

Rather than slashing departmental budgets, which Caballero Ledo called “not possible,” the prefect said instead that “we have to work hard to increase revenues,” though it is not clear where that new income would come from.

Global donations from the faithful and from dioceses around the world, including via the annual Peter’s Pence collection, make up about 30% of Holy See income annually — though with significant amounts of that money ring-fenced for charitable work.

According to the 2023 Peter’s Pence report, donations did track up modestly over 2022, rising by nearly 5 million euros, with the United States continuing to supply the largest block of donations at more than 28%, up from 25% the previous year.

Germany was previously a consistently high source of income for the Holy See, and a top contributing source of donations, fueled in large part by the Church in Germany’s extraordinary wealth generated by Church allocations from government income taxes.

However, Vatican relations with Germany’s bishops have been strained by years of disagreement over the controversial “synodal way” in that country, resolutions from which curial cardinals have repeatedly intervened to block.

At the same time, years of institutional disaffiliation among German Catholics have begun to impact revenue for the local Churches, leading to even the largest dioceses now forecasting budget deficits.

Germany accounted for only 2.7% of donations to Peter’s Pence last year, down from 3% the year before.

While some financial reforms have led to an increase in profitability for some Church assets, most notably the IOR, those results do not appear to be enough to cover the ongoing Vatican overspending — leading to short-term funding decisions, like the Peter’s Pence real estate sale in 2022.

Officials close to the Secretariat for the Economy have warned for months about a potential liquidity crisis, at which point, one official said, “options are limited and very bad things can start happening.”

While the IOR could act as a lender to the Holy See to meet immediate needs, several sources agreed this was not a sustainable prospect as it would destabilize the bank — whose customers include curial employees and religious communities and dioceses in developing parts of the world — and could even trigger regulatory issues with European financial inspectors if the bank’s owner (the Holy See) became its major lendee.

“After that stops working choices become very dark,” one source close to Vatican financial planning told The Pillar earlier this year, “either people stop getting paid, or assets start getting sold off, then you come dangerously close to a slow burning fire sale which can become a financial death-spiral.”

“People need to start thinking and talking about this now,” he warned, “because the alternative is everything is handled in a reactionary panic, and that only makes things worse.”

Comments 24

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews