Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger would have been a figure to be remembered in the history of the Church even if he had not been elected to the papal throne. In 2005, however, the Lord called one of the greatest living theologians, the man to whom Saint John Paul II entrusted the custody of Catholic orthodoxy for 23 years, to become Pope. Benedict XVI’s pontificate ended, traumatically, more than a decade ago as his earthly life ended a year ago, depriving the precincts of St Peter’s of that ‘service of prayer’ promised at his last general audience on 27 February 2013. Also in light of the new season under the banner of a claimed discontinuity at the dicastery for the doctrine of the faith, what has become of Ratzinger’s legacy in the current pontificate? This is a question the Daily Compass asked Peter Seewald, a German journalist, friend and biographer of Benedict XVI with whom he has written four interview-books.

Is it fair to say that the relationship between Benedict XVI and Francis was “very close”, as Francis recently declared?

Good question. We all remember the warm words that Cardinal Ratzinger spoke at the requiem for John Paul II. Words that touched the heart, that spoke of Christian love, of respect. But no one remembers Bergoglio’s words at the requiem for Benedict XVI. They were as cold as the whole ceremony, which had to be rather brief so as not to honour his predecessor too much. At least that was my impression.

Your judgement is harsh.

I mean, how does one manifest friendship? With a mere statement in words or by living it? The differences between Benedict XVI and his successor were great from the start. In temperament, culture, intellect and above all in the direction of the pontificates. In the beginning Benedict did not know much about Bergoglio, except that as a bishop in Argentina he was known for his authoritarian leadership. He promised his successor obedience. Francis obviously regarded it as a kind of blank cheque. Even his predecessor remained silent so as not to give the slightest impression of wanting to interfere in his successor’s governance. Benedict trusted Francis. But he was bitterly disappointed several times.

What do you mean by this?

Bergoglio continued to write nice letters to the Pope Emeritus after his election. He knew he could not hold a candle to this great and noble spirit. He also repeatedly spoke of the gifts of his predecessor, calling him a ‘great Pope’ whose legacy will become more evident from generation to generation. But if one really speaks of a ‘great Pope’ out of conviction, shouldn’t one do everything possible to cultivate his legacy? Just as Benedict XVI did with regard to John Paul II? As we can see today, Pope Francis has done very little indeed to remain in continuity with his predecessors,.

What does this mean in concrete terms?

Bergoglio is not a European. He has little knowledge of our continent’s culture. Above all, he seems to have an aversion to the westernised traditions of the Catholic Church. As a South American and a Jesuit, he has erased much of what was precious and dear to Ratzinger. Decisions were mostly made autocratically by a small circle of followers. Suffice it to recall the ban on the Tridentine Mass. Benedict had built a small bridge to a largely forgotten treasure island, which until then had only been accessible through difficult terrain. It was a matter close to the German Pope’s heart and there was really no reason to tear down this bridge again. It was obviously a demonstration of the new power. The subsequent purge of staff completed the picture. Many people who supported Ratzinger’s course and Catholic doctrine were ‘guillotined’.

Are you talking about the former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig Müller, and the case of Monsignor Georg Gänswein?

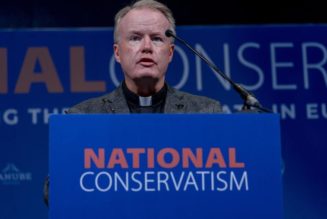

It was an unprecedented event in the history of the Church that Archbishop Gänswein, the closest collaborator of a highly deserving Pope, the greatest theologian ever to sit on the See of Peter, was thrown out of the Vatican in disgrace. He was not even given a word of pro forma thanks for his work. Of course, the purge primarily concerned the man whose lineage Gänswein represents, Benedict XVI. More recently, it was US Bishop Strickland, Benedict’s friend and critic of Bergoglio, who was removed from office on the pretext of financial misconduct; an obviously implausible reason. And when a Ratzinger supporter like 75-year-old Cardinal Burke is deprived overnight of his home and salary without any explanation, it is difficult to recognise the Christian fraternity in all this.

You mentioned the lack of continuity: do you think a document like Fiducia supplicans would have been published if Benedict XVI had still been alive?

In his small monastery in the centre of the Vatican, the elderly Pope Emeritus acted like the light on the mountain. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben also sees it as a katechon, a restraint, based on the Apostle Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians. The term katechon is also interpreted as ‘obstacle’. For something or someone stands in the way of the end times. According to Agamben, Ratzinger, as a young theologian, in an interpretation of St Augustine distinguished between a Church of the wicked and a Church of the righteous. From the beginning, the Church was inextricably mixed. It is both the Church of Christ and the Church of the Antichrist. From this point of view, Benedict’s resignation inevitably led to the separation of the ‘good’ Church from the ‘black’ Church, the separation of the wheat from the chaff.

However, Hong Kong’s Cardinal Joseph Zen recently pointed out that Benedict himself had repeatedly warned of the “danger of a doctrinal landslide”. When I asked Pope Benedict why he could not die, he replied that he had to stay. As a kind of memorial to the authentic message of Christ.

What are the most critical aspects of Fiducia supplicans?

In his speeches, Pope Francis says many right things. But a pastor, as the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa (presumably a genuine candidate for the next conclave) recently clarified, should on the one hand “listen to the flock”, but on the other hand “also lead, offer guidance and say where they should go”. Pizzaballa said: ‘One must not make oneself dependent on the expectations of others. The problem with Francis in the past has been that he has failed to keep many of his promises, sometimes saying ‘white’ and sometimes ‘black’, making ambiguous statements, contradicting himself repeatedly and causing considerable confusion. In the case of a document like Fiducia supplicans, which can be interpreted in so many different ways, there is also the fact that what has just been considered correct is suddenly declared wrong without much of a decision maturation process. Not to mention the divisive effect this has on the Church and the absolutely disastrous timing of its publication. The big issue before Christmas was not the commemoration of Christ’s birth, but the apparently much more important blessing of same-sex couples by the Church. The media far from the Church were enthusiastic about it and no one thought about the fact that such an important document was not – as was customary under Benedict XVI – discussed and approved by the Plenary Assembly of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, but was simply decreed autocratically.

In your opinion, would Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, author of the Declaration, have been appointed head of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith even if Benedict XVI had remained alive?

Difficult to say. Francis and his circle could assume that although the Emeritus was faithful to his promise of obedience, he would no longer remain silent if the level of destruction of the Church, which God apparently allowed, became unbearable. Immediately after his death, the considerations that were still valid during his lifetime were abandoned. It became right that a man like Víctor Manuel Fernández, who was quickly given a cardinal’s hat, should be appointed to the post of Prefect for the Doctrine of the Faith. The Argentinean is not qualified for this important task, except for one thing: he is the protégé of an Argentinean Pope. Until now aptitude was the main criterion for these appointments, but under Bergoglio it seems that loyalty to the line counts. Even before taking office, Fernández had announced a kind of self-demonisation of the Catholic Church. He wanted to change the catechism, relativise Bible statements and question celibacy. He knew he would not have much time left. He realised that he would not be able to stay with any subsequent pope. He was in a hurry. So he immediately raised his leader’s attitude towards the new doctrine. One speaks then of an expanded understanding of things. This is the door to be able to legitimise previously unknown interpretations of the Catholic faith.

In the future, the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith will no longer be needed as a watchdog office for the true Catholic faith, Francis explained, but as a promoter of the charisma of theologians. Nobody knows what this actually means. Reality is always more important than the idea, he added. Put simply: what is important is not what the Council, for example, said about the faith, but what is asked. At the same time, Francis softened John Paul II’s article on the organisation of the dicastery, which concerned the protection of the ‘truth of the faith and the integrity of morals’.

Above all, Fernández should ‘take into account the most recent magisterium’ in his interpretations, namely that of his Argentine mentor. It seemed a quid pro quo that the Pope exempted the new Prefect for the Doctrine of the Faith from having to deal with sexual abuse in the Church. Ratzinger, his predecessor in the post, had however brought this area under his authority because he saw that elsewhere crimes were swept under the carpet and victims left alone. However, Fernández is no stranger to this topic. The Argentine daily ‘La Izquierda Diario’ reported that, as archbishop of La Plata, he had covered up at least eleven cases of sexual abuse by priests ‘in various forms’.

Another proof of discontinuity was the repeal of the liberalisation of celebrations in the extraordinary form of the Roman rite. In the letter to the bishops accompanying the publication of Traditionis Custodes, Francis said that the intention of Summorum Pontificum had been ‘often gravely disregarded’. Has Benedict XVI really failed so badly with the so-called Latin Mass?

On the contrary. Ratzinger wanted to pacify the Church without questioning the validity of the Mass according to the 1969 Roman Missal. “The way we treat the liturgy,” he explained, “determines the destiny of the faith and the Church”. Francis, on the other hand, described the traditional forms as a “nostalgic disease”. If the intention had indeed been ‘gravely disregarded’, it would have been appropriate firstly to obtain an opinion from Benedict XVI and secondly to justify this accusation. But there is no investigation into this, let alone any documentation of the alleged cases. And the claim that the majority of bishops voted in favour of repealing Benedict’s ‘Summorum Pontificum’ in a worldwide poll is not true, according to my information. What I find particularly shameful is that the Pope Emeritus was not even informed of this act, but had to learn about it from the press. He has been stabbed in the heart.

First he spoke of abuse. You, who reconstructed the facts of Father Peter H.’s case in the biography ‘Benedict XVI – A Life’, can you explain why Msgr. Bätzing was wrong when he asked Ratzinger to apologise for his handling of the abuse as Archbishop of Munich?

The president of the German Bishops’ Conference knows that no one else in the Catholic Church has taken such decisive steps in the fight against sexual abuse as the former prefect of the faith and pope. Italian journalist Gianluigi Nuzzi said that Benedict has ‘removed the cloak of silence and forced his Church to focus on the victims’. He has done much more than Pope Francis against this scandalous evil.

Bishop Bätzig’s claim that the Pope Emeritus did not apologise for ‘what was done to the victims with the transfer of an abuser’ is pure misinformation. One thing is certain: in his statement of 6 February 2022, following the discussion on the much-discussed Munich report, the Pope Emeritus made it clear that he could ‘only express once again my deep shame, my great sorrow and my sincere apology to all victims of sexual abuse’. He has ‘assumed a great responsibility in the Catholic Church. My sorrow is even greater for the crimes and errors that have occurred during my tenure and in the places concerned […] The victims of sexual abuse have my deepest sympathy and I regret each and every case’.

With regard to the case of the priest Peter H. from Essen, dating back to the time when Ratzinger was bishop of Munich, the team of legal advisors of the Pope Emeritus came to the conclusion that the former bishop of Munich, as he himself stated, was neither aware that the priest “was an abuser nor that he was used in pastoral care”. The lawyers summarised that the report ‘contains no evidence of an allegation of misconduct or assistance in a cover-up’. The documents unreservedly support Benedict XVI’s statements.

You met him often even after his resignation: is it true that Benedict XVI had been very concerned in recent years about the situation in the German Church and in particular about the consequences of the so-called Synod path?

Ratzinger repeatedly expressed this concern also as Prefect for the Doctrine of the Faith. In fact, he had already felt offended after the Second Vatican Council, when he criticised its watering down and reinterpretation. He accused the Catholic establishment in his country of displaying mostly busyness, self-promotion and boring debates on structural issues “that completely miss the mission of the Catholic Church” instead of a “dynamic of faith”. He said it is a huge mistake to think that it is enough to wear a different cloak to be loved and recognised by others again. Christianity can only be a true partner in the difficult issues of modern civilisation through its resolutely presented ethics.

For Ratzinger, renewal consists in rediscovering the fundamental competences of the Church. Reformation, he emphasised, means preserving in renewal, renewing in preservation, to bring the witness of faith with new clarity into the darkness of the world. The search for what is contemporary must never lead to the abandonment of what is true and valid and to adaptation to what is current. In this regard, he was sceptical of the elitist ‘synodal path’, whose practitioners are in no way legitimised by the people of the Church. Moreover, as he grew older, this development saddened him greatly. During one of our meetings, he had to ask himself how many dioceses in his country could still be called Catholic in terms of leadership.

He was not resigned to this. He also saw the many youth initiatives that are rediscovering Catholicism and thus attracting more and more people, while on the contrary those that claim to be particularly contemporary are not only experiencing increasing spiritual dryness, but also an impoverishment of personnel, not to mention a loss of members. But even if the current situation of the Church and the world did not give cause for rejoicing, the Pope Emeritus always added in our conversations what he was deeply convinced of: ‘In the end, Christ will prevail!