Is Pope Francis set to dramatically remake the U.S. episcopacy?

Speculation has swirled throughout his 10-year pontificate that the Pontiff might appoint a slew of new bishops with more progressive theological views than the American status quo.

Some have been elated by the prospect; others fearful. But by and large, Church watchers tell the Register that Francis has done no such thing.

Instead, most commentators agree that while the Pope’s most high-profile episcopal picks may fit a certain progressive profile, the majority of U.S. bishops he has selected during his 10-year pontificate are notable for being good pastors — not holding certain theological opinions.

“It doesn’t seem at all obvious that Pope Francis has been doing the sort of ‘deck stacking’ that some people clearly would like him to do,” said Stephen White, executive director of the Catholic Project think tank at The Catholic University of America. “In a certain sense, that’s the dog that didn’t bark.”

And now, with a significant number of diocesan sees potentially opening up in the next calendar year, including a disproportionately high number of archdioceses, the Pope’s track record is being scrutinized for signs of who might be next in line.

Of the 194 total Catholic dioceses in the United States, eight are currently vacant, while another 11 are “superannuated,” a term meaning that their bishop has reached the age of 75, when canon law requires that a letter of retirement be submitted to the pope, who can choose to accept it or not.

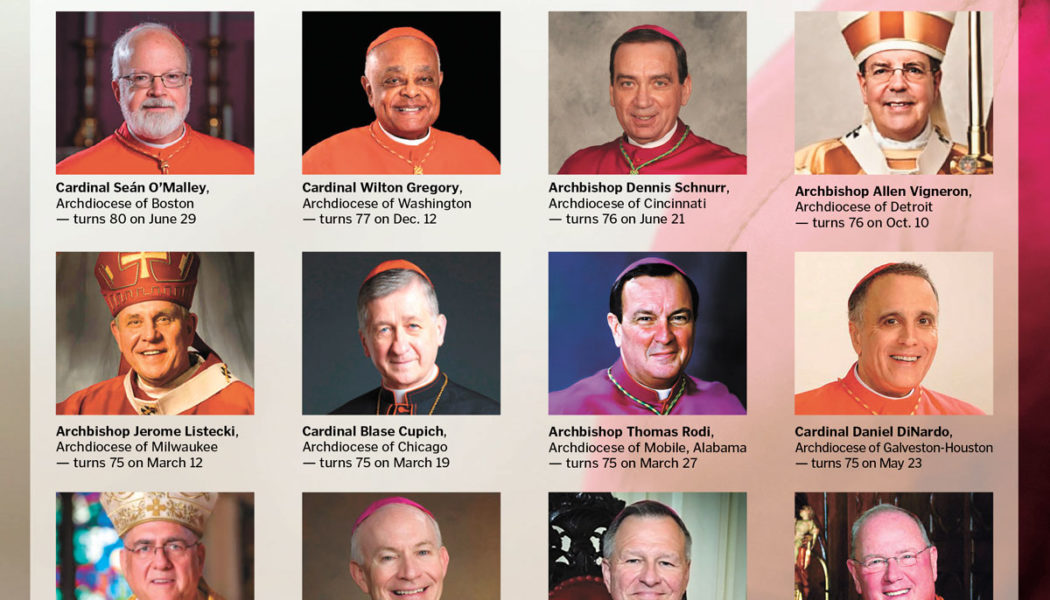

But the number of dioceses with a 75-plus-year-old ordinary will surge to 27 by March 2025, with archdioceses accounting for 44% of those potential openings.

The Archdioceses of Boston, Washington, Detroit and Cincinnati are already superannuated, with New York; Chicago; Galveston-Houston; New Orleans; Kansas City, Kansas; Milwaukee; Mobile, Alabama; and Omaha, Nebraska, set to join them over the next calendar year.

In total, 12 of America’s 33 Latin archdioceses are set to have ordinaries who will be at least 75 by March 2025, including figures like Cardinals Seán O’Malley, Timothy Dolan, Blase Cupich, Wilton Gregory and Daniel DiNardo, who have defined a generation of ecclesial life in the United States. (Archbishop Leonard Blair of Hartford, Connecticut, will also turn 75 this month, but his successor, coadjutor Archbishop Christopher Coyne, has already been named.)

Will Pope Francis move quickly to appoint their successors — and if so, with whom?

‘Behind Schedule’?

The high number of potential archdiocesan openings represents a unique opportunity for Pope Francis to make a significant impact on the highest levels of the U.S. episcopacy. But if the recent past is precedent, a dramatic overhaul is anything but guaranteed.

In fact, the left-leaning journalist Michael Sean Winters, who last year called on Pope Francis to “remake the U.S. hierarchy” by taking “some risks” in installing prelates who deviated from the typical U.S. bishop, acknowledged that things aren’t going quite how he envisioned.

“I think we’re behind schedule,” the National Catholic Reporter writer said. “If the Pope wants to remake the hierarchy in a more Francis-friendly vision,” which for Winters means downplaying abortion and sexual morality while being more inclusive, “we should be getting at least two appointments each month.”

The most recent bishop appointment, the Feb. 13 selection of Father James Ruggieri of Rhode Island to serve as the next leader of the Diocese of Portland, Maine, was the first new ordinary named in the last six months.

Michael Heinlein, a Catholic journalist and the biographer of the late Cardinal Francis George, said that instead of the barrage of new and more progressive U.S. bishops some have hyped up, “things are moving rather slowly.”

“There doesn’t seem to be a huge ‘full-speed ahead; let’s fill these slots while we can’ approach,” Heinlein told the Register. “Unless that’s a plan that’s in the works and will soon be revealed.”

‘Francis Bishops’

Since becoming pope in March 2013, Francis has appointed roughly half of the current U.S. bishops.

And in many ways, the Pope’s most recent choice is an example of a typical “Francis bishop.”

A priest of the Diocese of Providence, Bishop-elect Ruggieri’s 32 years of ordained ministry have been marked by pastoral service, including more than 20 years as pastor of the same parish and a food-truck apostolate that feeds the homeless once a week. Furthermore, the 56-year-old priest is known as someone who lives out the Church’s call to embrace a consistent ethic of life, advocating on behalf of the unborn, immigrants and the poor.

Other bishops who fit a similar profile include Bishop William Wack, who was ordained for the Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida, in 2017, and the Diocese of Sioux Falls’ Bishop Donald DeGrood, installed in 2020.

Like Bishop-elect Ruggieri, their work prior to the episcopacy was largely marked by pastoral work, including prison ministry for Bishop Wack and outreach to victims of clerical sex abuse by Bishop DeGrood. None of the three have advanced ecclesial degrees, nor are they known for emphasizing progressive theological views that deviate from the norm of the U.S. episcopacy.

Cardinal Marc Ouellet, who led the Vatican’s Dicastery for Bishops from 2010 to 2022, told EWTN News last year that the Pontiff looks for bishop candidates “who are witnesses of the Risen One and not just people that would be good administrators.”

Francis, the Canadian prelate added, wants bishops who are “full of life, able to evangelize, and also men of communion — not only of discipline, but of communion — able to listen to the people, to their priests, to their confreres in the episcopal conference.”

While suggesting that it would be “imprudent” to read too much into Francis’ appointments at this stage, Francis X. Maier, a senior fellow in the Catholic studies program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, cited an anonymous bishop he interviewed for his new book, True Confessions: Voices of Faith from a Life in the Church, who said that the Pope “seems to be looking for pastorally oriented men as bishops; guys who’ve been engaged in pastoral work.”

The bishop, according to Maier, described the approach as “an appropriate thing to do,” because “if you get careerists and technicians as bishops, guys who’ve spent most of their time just doing chancery work, it can really influence their episcopal ministry — and not in a good way.”

While “pastoral” might be used by some as a catchword for those willing to cut corners on Church teaching, White believes that for most Francis appointees, it genuinely seems to mean those who are concerned with their flock, are loyal to the Holy Father, and are reliably orthodox.

“There seems to be a pattern of pastoral priorities, but there doesn’t seem to be a clear ideological test,” said White.

Two-Tiered Appointments?

At the same time, Pope Francis’ broadly picks for the U.S. episcopacy have coincided with what some commentators suggest is a more specific set of criteria for the most high-profile appointments.

Heinlein, for instance, says the Pope’s picks for major U.S. archdioceses or to the College of Cardinals have been characterized by “more of an ideological common denominator.” In particular, he described these appointments as having a “progressive bent,” referring to theological views that were in vogue after Vatican II but fell out of favor during the pontificates of St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Prelates generally described in this way include Cardinals Cupich of Chicago, Gregory of Washington and Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, who were all given red hats and placed in charge of influential U.S. sees by Pope Francis. Like the pope who elevated them, these figures are part of the first generation ordained after Vatican II.

Russell Shaw, the former secretary of public affairs for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, told the Register that Pope Francis’ prioritization of theological progressives for prominent U.S. roles has coincided with the Pope “not raising to the rank of cardinal ordinaries in dioceses that, historically, have been headed by cardinals whose current incumbents he doesn’t see as supporters.”

Some point to Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles as an example. The 72-year-old Mexican-born prelate has led the largest archdiocese in the U.S. since 2011 but has been passed over in the nine consistories Pope Francis has convened.

In fact, in the most recent consistory to include a U.S. diocesan bishop, Cardinal Robert McElroy of the Diocese of San Diego, a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles with only a third of its Catholic population, was given the red hat. Cardinal McElroy is often described as the intellectual of the U.S. Church’s progressive wing.

What’s the explanation for this apparently two-tiered approach in Pope Francis’ U.S. bishop picks?

Some say that Pope Francis is more directly involved in prominent selections and that candidates picked for these sees more completely represent his priorities. If that’s the case, traditional cardinalatial sees like Boston, Washington and New York will be ones to pay special attention to in the coming months.

Others say that the apparent disparity between Pope Francis’ ordinary bishop appointments and ones to more prominent positions may be the result of who is advising him in different scenarios.

Heinlein suggested that the two American ordinaries on the Dicastery for Bishops, Cardinals Cupich and Tobin, have greater influence on high-profile U.S. picks, while more day-to-day appointments “are falling very comfortably in the prerogative” of Cardinal Christoph Pierre, the apostolic nuncio to the United States. Heinlein described the French cardinal as “very respected” among U.S. bishops of a variety of views and as a “unifying figure.”

Another possibility is that Pope Francis is interested in making more broad ideological shifts in the U.S. episcopacy but is having trouble finding eligible candidates.

Citing a recent survey by the Catholic Project, Heinlein pointed out that the American presbyterate is increasingly politically moderate, and priests are far less likely to describe themselves as theologically progressive.

“So when you’re looking for good bishop candidates, if ideology is what you’re looking for, you’re probably going to have a hard time filling the slots.”

Filling the Sees

In fact, finding new bishops in general appears to be increasingly difficult.

Cardinal Ouellet said as much in a 2022 interview, noting that the number of priests who decline an episcopal appointment had risen from 10% to “about three in 10” during his 12 years as head of the Dicastery for Bishops.

This might explain why it’s become commonplace under Pope Francis to keep bishops as ordinaries even after they submit their retirement letter.

Given the variety of factors in play, and that very few have direct knowledge of the inner workings of bishop appointments, commentators aren’t especially willing to make bold predictions for how Pope Francis may — or may not — fill all the U.S. diocesan ordinary slots potentially opening up this coming year.

“I would expect that we would continue to see men with broad pastoral experience, people who are probably moderates for the most part,” offered Heinlein. “If I were to guess, I think it’ll be business as usual.”

If so, it could lead to more “Francis bishops” for the U.S. Church that are less controversial than some might have expected—though, as White says, perhaps not intentionally.

“It’s worth considering that Rome thinks it’s making appointments that cut against the grain of what it believes is the mainstream of American Catholicism, but it isn’t because it doesn’t understand what the mainstream of American Catholicism is,” he said, adding that the Vatican seems to mistakenly think that firebrands like Bishop Joseph Strickland, who was removed from the Diocese of Tyler, Texas, in November, are representative of the U.S. episcopacy.

“There might be a sense in which Rome wants a certain kind of bishop, but it’s actually pushing on an open door, because, in most cases, that’s actually the kind of bishops that we already have and that we want more of.”