Today’s Gospel speaks of Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee and inviting an incredulous Peter to do the same. He starts out successfully then, lacking faith, begins to drown, only to be rescued by Jesus.

First, let’s address the miracle. Moderns may not be inclined to believe it; they may call it a nice “story” but deny its truth. Nobody can walk on water and why would anybody do so, anyway?

Aspects of our Western intellectual tradition are perhaps responsible for this refusal to believe, especially in miracles. Two philosophical currents — deism and logical positivism — conspire against it, especially in the Anglo-American mind (given the prominence of those currents in British and American thought). Deism turned the universe into a wind-up world characterized by God’s Real Absence — if there is anything like a “creation” (and post-Darwinians often insist our existence is happenstance and serendipity), it happened once. God set the rules and went off somewhere. He does not intervene in his cosmos. Logical positivism limits “reality” to what you can quantify and measure: if you can put it in a test tube, it’s real, if not, it isn’t. “Scientific” people don’t attribute “reality” to anything else. (I guess that means “truth” or “love” are not real, which implies scientists shouldn’t get married or accept anything they discover as “true.”)

Well, if either of those philosophical currents were true, there’s no need to pray, because God doesn’t change anything in the world. And since God can’t be quantified or measured anyway, just to whom are you “praying?”

Since I firmly believe that God not only created but sustains the universe in existence in every moment (because contingent matter is not self-supporting) and that “there are more things in heaven and on earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy” (Hamlet, Act I, Scene 5) I accept the truth of Jesus walking on water.

So now that we know we are working on Christian philosophical and theological grounds, why would Jesus do it?

First, let’s consider the role of miracles in the Synoptics (Matthew, Mark and Luke). John never calls them “miracles” but rather “signs,” because that is what they are: they signify fundamental truths about Jesus.

Let’s look at miracles in the context of Matthew. The miracles in the Synoptics fall into basically two categories: more common miracles of healing and less frequent miracles involving nature. Today’s Gospel represents the latter.

Jesus’ healing miracles, as I repeatedly note, are not because he is a “kind teacher” who is out to raise Israel’s public health standards. His healings point to whom he is: one who has come to restore man, to make him the glory of God as fully alive. Since sickness, decay and death are consequences of man’s fundamental disorder of sin, Jesus’ conquest of sin will then necessarily also have ramifications in man’s physical life and health.

Jesus’ nature miracles tell us that God is Lord of Nature. Nature is subject to him. God created it, including its laws, and God can change or suspend those laws, raising nature’s possibilities beyond the ordinary and expected.

This perspective is especially vital today, because there are aspects of the modern environmental and climate movements that border on, if not reach to, pantheism. There is a tendency to deify “Mother Earth” and, conversely, to denigrate human beings as overgrown carbon footprints. It hasn’t attained (yet) to suicide but it has reached to killing off the next generation: how many young people say they aren’t getting married or having children “for the planet?”

This is not a Catholic understanding of nature. The recognition that God created the universe goes in tandem with God’s entrusting that world to human dominion (Genesis 1:28). Having created man in his Image — and thus qualitatively different from the rest of the physical world — God entrusted man with stewardship over the world. Stewardship forbids abuse but it includes use of creation. Man shares in God’s co-creatorship: he made trees but left it to man to make tables. The apotheosis of nature, a tool entrusted to man’s responsible use, cannot justify a reductionism that undermines man’s distinct status as being made in God’s image and likeness, the only creature God made for himself.

Today’s Gospel has a lot to say about God, man and nature even before we get to the question of faith.

And there is a question of faith. Let’s reset the story. Jesus has multiplied the loaves and fishes to feed a hungry multitude (obviously, another miracle of nature). He then went off on his own to pray, sending the Apostles ahead of him by boat when they find themselves on a choppy sea.

They see Jesus approaching on the waters but are “terrified.” “It’s a ghost,” they declare.

In Matthew’s Gospel (unlike this month’s liturgical calendar), the Transfiguration is yet to come, but one of the realities of the Transfiguration is that Christ’s human body acquires characteristics our present humanity lacks. The Transfiguration is not just Jesus shining while Moses and Elijah have a conversation with him. It points to the transformation of his body beyond what we think is possible: first in the Eucharist, obviously in the Resurrection, eventually encompassing us in the Resurrection of the Body on the Last Day. So tonight’s encounter on the Sea of Galilee is, arguably, a mini-Transfiguration. And while perhaps they don’t recognize the “ghost,” their eyes will eventually be opened in faith. Think, for example, Emmaus.

Once more, of course, Jesus tells his Apostles what he repeatedly tells them, and us: “Do not be afraid!”

That, of course, triggers our friend, never-without-something-to-say Peter almost to test Jesus: “if it’s you, tell me to come” to you. He does.

Peter has enough faith to start out. That modicum of faith sustains him. He goes forward.

Then he starts thinking, a process that often hurts human beings. This can’t be happening! It’s impossible! It can’t be (even though it clearly is)! And so, he starts to sink.

Think of a child on a bicycle. As long as the child is focused on his father, he starts moving. He is riding the bicycle. Then he realizes what he’s doing and, suddenly, he gets scared, loses his balance, and falls. “You of little faith!”

“Lord, save me!” cries Peter. At some point in life we are all Peters.

“If you had the faith the size of a mustard seed, you could tell this mountain to uproot itself and it would.” But we don’t. Because we measure by our limited standards rather than trusting God.

We lack faith that God’s Providence will protect us. We lack faith that God exists or, if he does, is there for us. But if God is for us, who can be against us? (Romans 8)

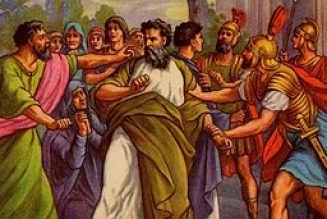

Today’s Gospel is illustrated by the 19th/20th century Scottish artist, William Brassey Hole (1846-1917). We’ve met him before.

Hole’s work makes us a witness to the scene: we see both the Apostles in the boat and Jesus on the lake. The one with outstretched arms is most likely Peter, calling to Christ to call him. Jesus, traditionally in white, seems almost ghostlike, though his physique and appearance is also “Jesus-like.” The waves are not stormy but not calm, either.

It’s night, obvious by the darkness and the full moon: I note this because, while the Gospel also establishes that chronology, there are some paintings of this scene in fuller daylight. In Hole’s painting, the light clearly illumines Jesus and the path to him, while the Apostles are more in the shadows. It’s likely not just an artistic device: faith illumines the path to Jesus, a light by which these men are not yet fully prepared to walk. Many depictions of this scene will split the light in this way: see here and here.

Hole was strongly devoted to Scotland. Scottish historical themes and Biblical works figure strongly in his painting. As a young man, he spent time in Italy — almost an obligatory destination for aspiring European artists — and in 1900 visited the Holy Land to acquaint himself with the land and appearances of Israel for what eventually became an 80 watercolor set illustration of The Life of Jesus of Nazareth.

One final observation on Jesus and nature. I noted above that this miracle on the Sea of Galilee follows in Matthew immediately on Jesus’ multiplication of the loaves to feed the hungry crowd. The same is true in John (6:16-24) where, at first glance, it seems almost an intruder into Jesus’ Bread of Life discourse, which starts with the multiplication of the loaves and ends with his extensive teaching on the Eucharist, resulting in many of his disciples refusing to believe him and walking away. Stacy Trasancos and Father George Elliott in their book on the Eucharist, Behold! It Is I! contend there is nothing at all intrusive about the miracle on the Sea. They argue the miracle is in fact intended to challenge the reader to consider what is possible with God — because the Eucharist is an even greater (and more commonplace) miracle than waterwalking — while also noting that if one cannot believe in the former, how will one believe that God takes the appearances of bread and wine?

So, the question to Peter is also the question to me: am I one of “little faith?”