Some Catholics are not sure what to think of biological evolution. They hear from their evangelical Protestant friends and neighbors that it is contrary to Christian belief, but they do not hear much on the subject one way or the other from authorities in the Catholic Church. For example, the topic is never explicitly mentioned in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. My purpose in this article is to sketch in broad outline what the Church’s position has been and to answer some common objections to evolution made by Christians who are skeptical of it.

When people speak about “evolution,” they can mean different things. So, one must distinguish several layers to the theory of evolution.

First, there is the basic idea of evolution, which is that the present species of living things arose from earlier species by a gradual process of development, and that ultimately all of them came from a single original form of life. This is sometimes called “common descent” since it says that all known forms of life on earth descended from a common ancestor. Second, there is the evolution of mankind in particular, i.e., the idea that human beings evolved in the same way and are thus part of the same branching tree of life. However, here we must make a distinction: do we mean the evolution of only the human body or of both the body and the spiritual soul? As we shall see, that is an all-important question. And third, there is the mechanism of evolution, which according to Darwinian theory is primarily natural selection acting on random genetic mutations.

Public discussions of evolution and religion are often dominated by fundamentalist Christians on the one hand, who reject evolution on the basis of narrowly literalistic readings of the Bible, and militant atheists on the other hand, who draw sweeping conclusions of a philosophical character from evolutionary science. But what has the Catholic Church had to say on the subject?

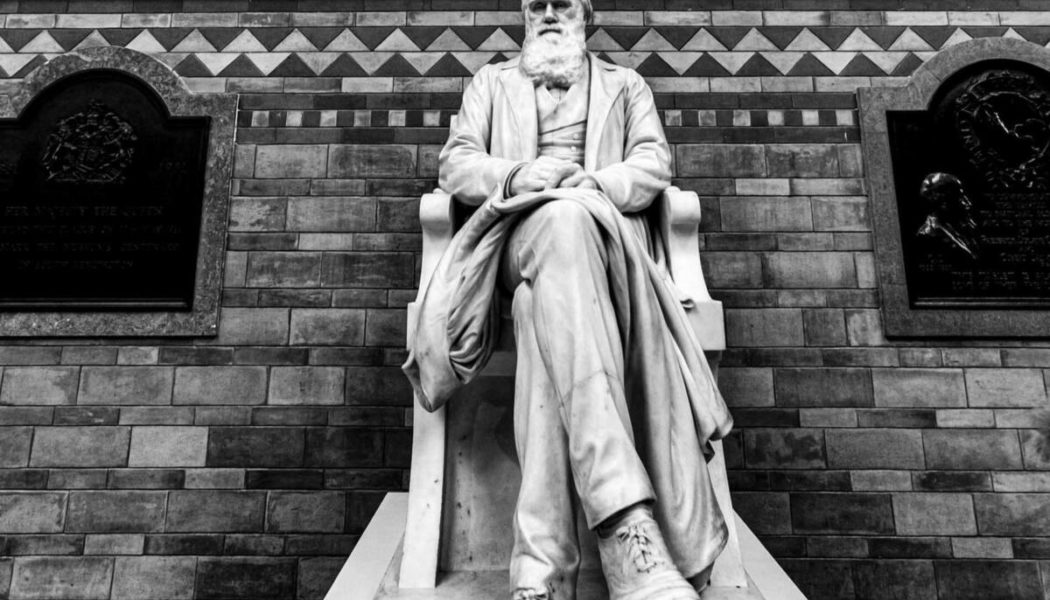

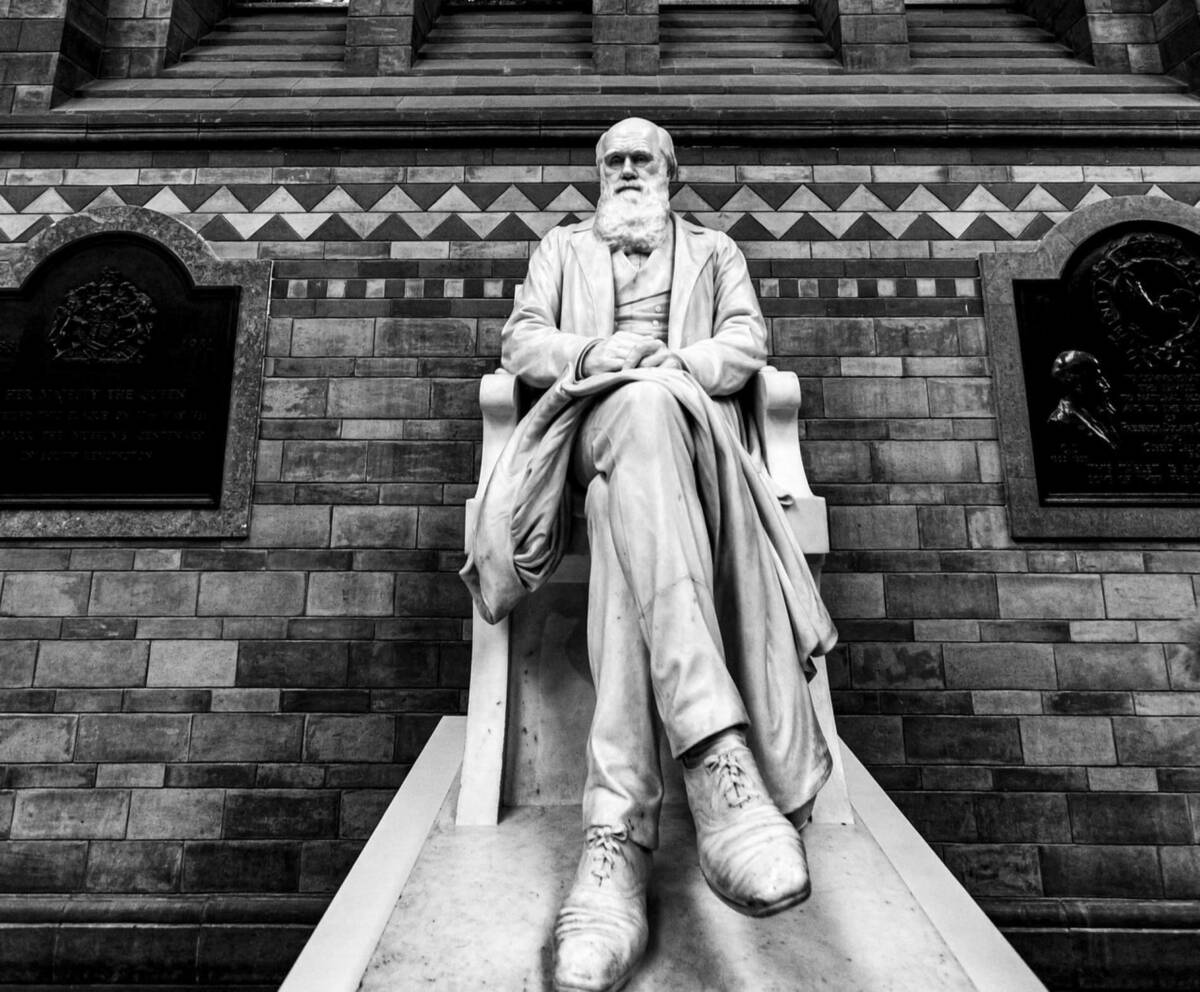

As far as official teaching goes, i.e., pronouncements of the magisterium, the Church said virtually nothing for almost a hundred years after Darwin published his theory in 1859. However, some sense of the general attitude of Catholic scholars and theologians toward evolution in the early days of the theory can be gotten from looking at the old Catholic Encyclopedia, which was written in the first decade of the twentieth century. Of course, this had no magisterial authority, but it was one of the outstanding products of Catholic scholarship at that time in the English-speaking world and carried an imprimatur certifying that it contained nothing contrary to Catholic doctrine.

The article in the encyclopedia entitled “Catholics and Evolution,” first summarized the theory of evolution as it stood at that time, and then said:

This is the gist of the theory of evolution as a scientific hypothesis. It is in perfect agreement with the Christian conception of the universe.

An impressive book of Catholic apologetics called The Question Box was published around the same time. In a question-and-answer format, it responded to hundreds of common objections to the Catholic faith. This book sold several million copies and seems to have been given to students in Catholic high schools in those days—I have my mother’s old copy, dating from her high school days in the 1930s. In answer to the question on page eight, “May a Catholic believe in evolution?”, the book said:

As the Church has made no pronouncement upon evolution, Catholics are perfectly free to accept evolution, either as a scientific hypothesis or as a philosophical speculation.

What both of these books were discussing in the sentences just quoted was the evolution of species in general. On the evolution of mankind in particular, they were much more cautious. They pointed out that the human soul, being spiritual, cannot be reduced to matter (it goes beyond physics, chemistry, or biology) and therefore cannot be explained by any merely material process, such as biological evolution. Evolution of the human spiritual soul is therefore contrary to the Catholic faith. On whether the human body evolved, these articles came to no conclusion. The encyclopedia admitted that it was “per se not improbable” that the human body had evolved, and noted that a version of this idea had “been propounded by St. Augustine.” However, the authors of both articles thought the scientific evidence for human evolution as it then stood was weak and observed that most theologians of that era had a negative view of the idea. Nevertheless, they admitted that there was no official Church teaching on the matter.

As far as the mechanism of evolution was concerned, little was said. The idea that evolution of plants and animals was a natural process did not seem to be a problem for the Church. This is an area where the Church’s philosophical traditions served her very well. Many opponents of evolution see Nature as being somehow in competition with God, so that the more we attribute to natural processes or natural causes, the less we can attribute to God, and vice versa. But the Church has never accepted this dichotomy. She has always understood that there are two levels of causality, which are called by theologians “primary” and “secondary” causality.

These concepts are best explained by a simple analogy. Consider the play Hamlet. In that play, the character Polonius dies because the character Hamlet stabs him through a curtain. So, one could ask the question: did Polonius die because the character Hamlet stabbed him, or did he die because Shakespeare wrote the play that way? The answer, of course, is both. The character Hamlet and the playwright Shakespeare are both causes of Polonius dying, but they are causes on different levels. Hamlet is the cause within the plot of the play, the horizontal cause, one might say; whereas Shakespeare is the cause of the play and of its entire plot, the vertical cause. These two kinds of causality are obviously not in competition.

By analogy, the events in the physical world have amongst themselves various horizontal causal relationships. Theologians traditionally called these “secondary causes” rather than horizontal causes and God, as the Author of the whole universe and of its whole plot, is the vertical cause, or as theologians say the “Primary Cause.” There is no contradiction or competition between the two. Rather God’s primary causality undergirds all secondary causality: the fact that one physical event can cause another in the natural world is ultimately because God has created a world in which such causal relationships exist. So, if one were to ask whether some species of animal, say hippopotamus or giraffe, arose through a sequence of natural secondary causes within the plot of the universe, as described by evolution, or because God wrote the plot of the universe that way, the answer a Catholic would give is both.

This basic insight about primary and secondary causality is related to another insight of traditional Catholic teaching, which is that God in his divine nature is outside the flow of time. He sees from all eternity the whole pattern of history from beginning to end, which unfolds according to his plan. The idea of his having to intervene repeatedly to take care of unforeseen problems or that he is, as it were, making it up as he goes along, is utterly alien to Catholic thought, which sees God as creating everything, what to us is past, present, and future, by a single all-encompassing act of his will.

The Question Box used an analogy:

A billiard player wishes to send a hundred balls in different directions. Which will require greater skill—to make a hundred strokes and send each ball separately to its goal, or, by hitting one ball, to send all the ninety-nine others in the directions which he has in view?

The Catholic Encyclopedia put it this way:

If God produced the universe by a single creative act of His will, then its natural development by laws implanted in it by its Creator is to the greater glory of His divine power and wisdom.

The encyclopedia went on to quote St. Thomas Aquinas and Francisco Suarez:

St. Thomas says, “The potency of the cause is greater the more remote the effects to which it extends”; and Suarez [says], “God does not interfere directly with the natural order where secondary causes suffice to produce the intended effect.”

The Church has always taught that there is a natural order that comes from God, and the greater the powers and potentialities that God has implanted in Nature, the more it shows forth his power and greatness. To be sure, these old Catholic articles on evolution condemned atheist interpretations of it, which deny the existence of God or his providential governance of the world. However, they sharply distinguished such philosophical extrapolations from evolution as a biological theory.

Were these two articles atypical of Catholic thinking? I don’t think so. For example, John Henry Newman, later Cardinal Newman, and now St. John Henry Newman, is considered by many the greatest Catholic theologian of the nineteenth century. Newman wrote in a letter to the Rev. David Brown in 1874:

I see nothing in the theory of evolution inconsistent with an Almighty Creator and Protector.

In 1868, he wrote:

Mr. Darwin’s theory need not, then, be atheistical . . . it may simply be suggesting a larger idea of divine Prescience and Skill.

Even earlier, in 1863, he wrote in one of his notebooks:

There is as much want [i.e., lack] of simplicity in the idea of creation of distinct species as in that of the creation of trees in full growth whose seed is in themselves, or of rocks with fossils in them. I mean that it is as strange that monkeys should be so like men with no historical connection between them as the notion that there should be no course of history by which fossil bones got into rocks.

Note Newman wrote this only four years after Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

In 1908, G.K. Chesterton, perhaps the most popular Catholic author of his time, wrote in his marvelous little book, Orthodoxy:

If evolution simply means that a positive thing called an ape turned very slowly into a positive thing called a man, then it is stingless for the most orthodox. For a personal God might just as well do things slowly as quickly, especially if, like the Christian God, he were outside time.

The first official pronouncement of the Church on the subject of evolution did not come until 1950, when Pope Pius XII issued his encyclical letter Humani Generis. The Pope specifically addressed the question of the evolution of man. His central point was that one must distinguish the origin of the human body and the origin of human spiritual soul. The evolution of the spiritual soul, of course, he rejected as inconsistent with the Catholic faith. On the evolution of the human body, he still took a very cautious stance. He said that Catholic scholars could investigate it as a “hypothesis” as long as they did not jump to any conclusions rashly. Though he was obviously less convinced by the evidence than were most scientists of that time, it is clear that he thought the matter was to be decided by the evidence and that he was willing to let the chips fall where they may.

Another point that Pope Pius XII addressed was the question of “monogenism” versus “polygenism”; that is, whether all human beings were descended from a single original pair of humans (call them Adam and Eve) or many. He said that Catholic scholars could not “embrace” the idea of polygenism. However, he did not absolutely close the door to polygenism. He said that “it is in no way apparent” how polygenism could be reconciled with certain Catholic teachings, in particular on Original Sin. But his precise wording is significant. He did not assert that these ideas could not be reconciled, only that it was not apparent how they could be. In recent times, many Catholic theologians have abandoned monogenism, because they think that the theory of evolution requires polygenism. It would, if the emergence of true human beings with spiritual souls were simply a matter of biological speciation. I will return to this question later.

The next notable Church statement on evolution did not come for nearly a half-century later. In 1996, Pope John Paul II delivered an address about evolution to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Referring to the encyclical Humani Generis, he said:

Today, . . . half a century after the appearance of that encyclical, some new findings lead us toward the recognition of evolution as more than a hypothesis. In fact, it is remarkable that this theory has had progressively greater influence on the spirit of researchers, following a series of discoveries in different scholarly disciplines. The convergence in the results of these independent studies—which was neither planned nor sought—constitutes in itself a significant argument in favor of the theory.

Of course, the Pope was not officially teaching that evolution is true. The Church does not claim to have competence in deciding scientific questions. The Pope was simply recognizing an obvious fact, namely that there was a great deal of evidence for evolution and significantly more than there had been in 1950.

Pope John Paul II in the same message reiterated what he called “the essential point” made by Pope Pius XII, namely that “if the human body takes its origin from pre-existent living matter, [nevertheless] the spiritual soul is immediately created by God.” (“Immediately” here, means directly, i.e., not simply as a consequence of natural secondary causes.) This has always been the essential point for Catholics. Evolution is ultimately nothing but a theory of how atoms came to be assembled in certain ways to form biological organisms. However, we human beings are not just assemblages of atoms. We are also spiritual, in that we have rational intellects and free will, which cannot be explained merely in terms of the motions of atoms. That means that there is not just a difference of degree between us and other animals, but what Pope John Paul II in the same message called an “ontological discontinuity.”

The next important statement was a document issued in 2004 by the International Theological Commission, which is a body that advises the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, at that time headed by Cardinal Ratzinger. The document, called Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God, was approved for publication by Cardinal Ratzinger. It analyzes some of the philosophical and theological issues surrounding evolution. It stresses the same points made by Popes Pius XII and John Paul II, but it contains more. In particular, it argues that the Darwinian mechanism of evolution is compatible with the Catholic doctrine of divine Providence. I will come back to this very important point later.

We see from all this that the Catholic Church and the best Catholic thinkers have never been caught up in anti-evolutionism.

Of course, the fact that some idea has never been condemned by Church authority does not mean that there may not be theological objections to it that should be taken seriously. So let us examine eight of the most commonly heard theological objections to evolution. I will start with the most flimsy and then take up the more substantial ones.

Objection 1: That evolution seems to some people to disagree with the biblical account of creation.

The Question Box answered this argument well:

The Bible is not a textbook of science, and, therefore, cannot rightly be quoted either for or against evolution. As Pope Leo XIII says in his encyclical Providentissimus Deus: “The sacred writers did not intend to teach men these things, that is to say, the essential nature of the things of the visible universe.”

One also should note that some of the Church fathers, including St. Augustine, took many of the things in the book of Genesis in a symbolic way. For instance, Augustine did not take the Six Days of creation literally as an actual sequence in time. He considered that the whole universe was created in one instant. St. Thomas Aquinas followed Augustine’s view on this. St. Thomas said that the idea of a temporally successive creation was more common and “superficially more in accord with the letter” of Scripture, but that St. Augustine’s view was more “in accordance with reason” and that therefore he, St. Thomas, preferred it.

Objection 2: That evolution seems to some to take away from human dignity, by saying that we are descended from apes.

However, it is not clear why being directly formed from the dust of the ground is more dignified. An ape is certainly something higher than dirt. In fact, the Bible in many places emphasizes that we are creatures of dust, precisely to show us our lowliness. Our dignity comes not from our physical antecedents, but from our spiritual nature. Only in the account of man’s creation do we find it said that “God breathed into him, and he became a living soul.” The Church Fathers understood this to mean that only upon man did God confer a spiritual nature in some way resembling his own, and that this is why only human beings are said by Scripture to be made in the image of God.

As it happens, science agrees with the Bible that we came from dust. Billions of years ago, there were just particles and dust from which condensed all stars and planets and living things. Whether we came from dust very quickly as portrayed in Genesis or through a slow process as described by science, is really theologically irrelevant, as Chesterton observed. Our bodies are taken from the dust and to dust they shall return.

Objection 3: That evolution seems to some people to imply that there is only a difference of degree between man and animals.

However, that conclusion would only follow if we deny what John Paul II called the “essential point”: that man has a spiritual soul as well as a body.

Objection 4: That evolution is “naturalistic.”

Some people think that explaining things naturally, rather than supernaturally, leaves God with less to do. This objection to evolution is puzzling. People hardly ever raise this objection to the natural explanations of things given in astronomy, geology, physics, or chemistry. It is only in biology that they see a problem with naturalism. However, we have already seen the fallacy involved in this point of view, namely failing to distinguish between primary and secondary causality.

Objection 5: That Darwinian evolution seems to some people be inconsistent with Christian belief in the Fall of Man and its consequences, one of which is death.

How can death be a consequence of Adam’s sin, they say, if animals were dying for hundreds of millions of years before the first humans appeared, and if indeed the first humans evolved through a process that involved life-and-death struggle, and if we therefore have a nature that has been shaped by that struggle?

The answer is that first of all the Church only teaches that human death is a consequence of the Fall. There is no Catholic doctrine linking the death of plants and animals to Adam’s sin. The Catholic view has been that bodily death is part of the natural order for all plants and animals, and indeed also for human beings because we are animals. So that when God in Genesis gave Adam and Eve the gift of bodily immortality he was giving what Catholic theology has traditionally called a “preternatural gift,” a gift that goes beyond what is natural. When the first human beings sinned, that gift was forfeited and human beings reverted to the condition of bodily mortality, which was as natural to them as to all of their animal forebears.

For example, St. Athanasius in the fourth century wrote:

[Human beings] were by nature corruptible [i.e., subject to decay and death], but were destined by the grace of the communion of the Word to have escaped the consequences of nature, had they remained good. Because of the Word and His dwelling among them, even the corruption natural to them would not have affected them.

And St. Augustine in the fifth century wrote:

For Adam, before he sinned, can be said to have had a body that was in one way mortal, but in another way immortal. . . . This [immortality] was provided him by the tree of life, and not by the constitution of his own nature. When he sinned, he was separated from that tree, so he was able to die, who, if he had not sinned, had been able not to die. He was mortal, therefore, by the condition of his body, but immortal by the kindness of the Creator.

Some have also asked how lust and violence can be a consequence of the Fall if they are part of our animal inheritance and bred into us by evolution. The very question is premised on a basic misunderstanding of Catholic teaching. The sin of lust is not to be identified with the sexual instinct and sexual attraction, which are not in themselves morally evil and which we undoubtedly have in common with animals. Otherwise, animals would be guilty of the sin of lust. Nor is anger, which animals also exhibit, in itself morally evil. Rather, sin comes from the failure to subject these passions to the control of reason. “Concupiscence,” i.e., the inclination toward sin coming from inordinate desires, which the Church teaches to be the consequence of the Fall, is the disorder within each human being whereby the control of reason over these passions is weakened, so that the passions often control us, rather than we controlling them. So, it is quite consistent to say that the passions themselves had a biological, evolutionary origin, whereas their subjection to reason (like reason itself) was a gift from above, a gift partly lost through sin.

None of the objections discussed so far should have any force for Catholics; and indeed historically they have had very little. So now let us turn to three, more serious objections.

Objection 6: That according to evolutionary theory a biological species arises by a gradual process over many generations by the spreading of genetic changes within a population, whereas both the Book of Genesis and the traditional Catholic view called monogenism state that the human race appeared suddenly with just two individuals.

Moreover, genetic evidence strongly implies that the human race is traceable to an ancestral population of several thousand interbreeding individuals, not just one pair.

The answer to this is also not complicated, and has been proposed by many people, including C.S. Lewis and various Catholic authors. Biological species do indeed arise gradually by genetic changes spreading throughout populations, but the human race in the theological sense is not just a biological species defined by its physical characteristics. We have spiritual souls. One either has an immortal spiritual soul or one does not. There are not degrees of having one. Thus, the transition from creatures that did not have spiritual souls to those who did was necessarily a sudden one. One can imagine that on the physical and biological level there was a long slow process of speciation, and that in the fullness of time, when some proto-human creatures had attained a level where they were capable of receiving spiritual souls, i.e., the powers of reason and free will, God conferred them on one pair out of a population of thousands. Or, if polygenism is true, God could have conferred this gift on many or all of them. This gift would not have destroyed their animal nature but raised it to a higher level.

One can think of this as one of a series of such transformative supernatural gifts. First, with the first humans, there was the gift of rationality and freedom that made them spiritual beings. (And this gift is repeated with every human child who is conceived. For, remember, that according to Catholic teaching the spiritual soul does not come through biological reproduction but is conferred directly on each person by God.) Second, there is the gift of the supernatural life of grace conferred in baptism. And finally, there is the gift of glorification and the beatific vision that the blessed enjoy in heaven. None of these gifts destroys what preceded it, but raises it to a new level that it could not have attained naturally.

Objection 7: That evolution destroys one of the traditional arguments for the existence of God, which philosophers call the “Argument from Design.”

For example, the atheist zoologist Richard Dawkins has said that evolution, by showing that the intricate structures of living things can arise by blind natural processes rather than having to be directly crafted by an intelligent agent, makes it possible for the first time to be “an intellectually fulfilled atheist.”

The answer is that even if evolution explains how the intricate structures of living things developed in a natural way it only affects certain versions of the Argument from Design. It would leave untouched arguments based on the orderliness and lawfulness of the cosmos as well as arguments based on “anthropic coincidences,” i.e., the fact that the laws of physics seem in many respects “tailor-made” to make life possible.

Objection 8: That evolution is fueled by random genetic mutations, and randomness seems inconsistent with divine providence.

If something happens by chance, doesn’t that mean God was not in control of it?

No less a theologian than St. Thomas Aquinas said that there is no contradiction. Book Three, chapter seventy-four of his Summa Contra Gentiles has the title, “Divine providence does not exclude fortune and chance.” I think that at some level everyone realizes this. Being Christians does not stop us from speaking about chance, accident, randomness, and probabilities in many everyday situations, and no one imagines that when we do we are saying anything atheistic. We say, for example, “I found the book quite by chance” or “there was a traffic accident on I-95.” Or we talk about a “random collection of objects.” We ask what the chance or probability is of winning the lottery or getting dealt a full house or three-of-a-kind in a game of poker.

Of course, God knew from all eternity that you would find that book, that the cars would collide on the highway, what would be in that random collection of objects, who would win the lottery, and what cards would be dealt in that poker game. Not only did he know, but he caused all these things as the Author of the universe and of its plot. Nothing escapes God’s knowledge or is outside his plan. So, from the vertical perspective of God, who is outside the flow of time, nothing is by chance, but from our horizontal perspective, crawling along through time, they are.

We know all this when it comes to everyday life, but for some strange reason, many people forget it when talking about evolution.

Chance, randomness, and probability play a role in many natural processes. The molecules in the air move around randomly. Certain animals spawn vast numbers of offspring. Why? To compensate for the fact that the chances of any one of them surviving is low. Why are so many sperm sent off in search of the egg? Because the chances of any one sperm accomplishing its task are exceedingly small. It is not clear why God should not achieve his ends in a similar way in evolution also. If God can so arrange things that many larvae are produced so that a few of them shall win out and survive to adulthood, why should he not arrange that many genetic mutations should occur so that some of them shall win out to produce new and interesting creatures?

In conclusion, the Catholic Church has never had a quarrel with the idea of evolution or with the Darwinian theory of natural selection acting on random genetic mutations. These theories pose no danger to traditional Catholic belief or orthodoxy. Catholics are therefore free to follow the evidence wherever it may lead. That is what the Church has wisely taught and continues to teach.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article is part of a collaboration with the Society of Catholic Scientists (click here to read about becoming a member). You can find the original version of this article here with extensive footnotes.