When I was a young seminarian I studied moral theology under the tutelage of the late, great Germain Grisez (1929-2018). I did not agree with all aspects of his “new natural law” theory, but his deep devotion to Catholic orthodoxy and his stout defense of Humanae Vitae in the face of fierce criticism impressed me. But what impressed me even more was his unwavering commitment to rigorous, free, and open scholarly debate, which gave him a deep charity toward proportionalist moral theologians with whom he was engaged in debate. This led him to instill in us a sense of deep intellectual fairness to our interlocutors, eschewing all forms of “straw man” argumentation and having a rigorous devotion to accurate representation of all pertinent theological data.

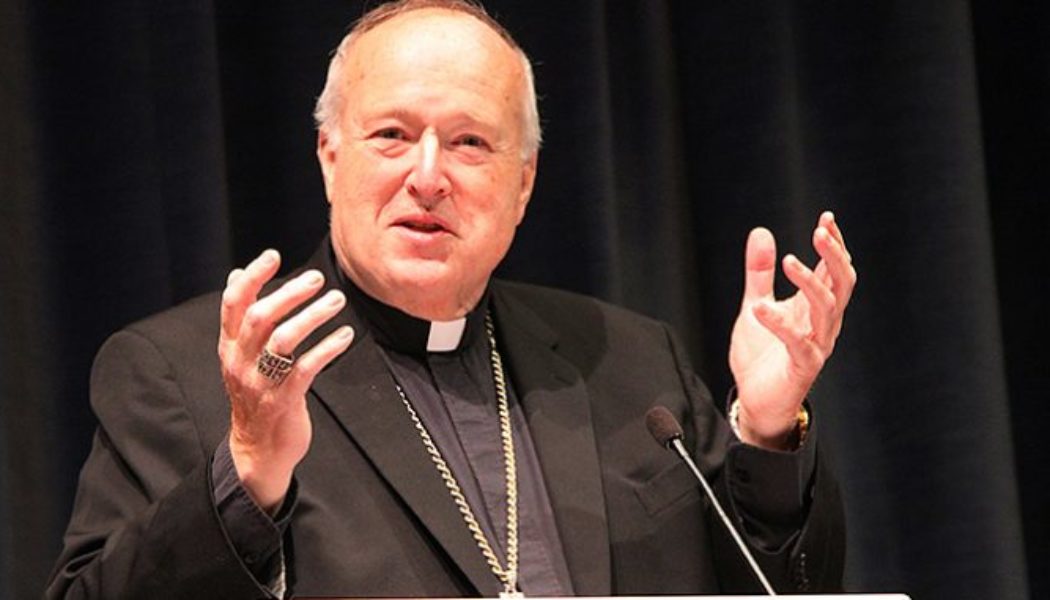

Unfortunately, Cardinal Robert W. McElroy’s “latest “clarification” of his views on Catholic moral theology in matters of sexuality displays none of the qualities of fairness, rigor, and accuracy championed by Grisez. I think that should matter. Furthermore, there really is nothing in his latest missive that clarifies anything at all and is rather a mere doubling-down on, and a repetition of, what he has said before. He does not, in any specific way, deal with the substance of his critic’s arguments, but simply does an end-run around them by proffering the same straw man arguments as in his previous America magazine essay.

McElroy’s primary issue is with the moral conclusions that have been drawn within the Church’s traditional moral theology.He once again explicitly rejects the notion that all sexual sins have as their moral object acts which constitute “grave matter”:

The moral tradition that all sexual sins are grave matter springs from an abstract, deductivist and truncated notion of the Christian moral life that yields a definition of sin jarringly inconsistent with the larger universe of Catholic moral teaching. This is because it proceeds from the intellect alone.

The clear agenda is to legitimate the view that most sexual sins are “merely” venial, if indeed sins at all in many cases. Should the Church adopt his views, McElroy has to know that the net effect would be, on a practical level, that most Catholics would now simply adopt an utterly relativistic and latitudinarian approach to sexual morality. They would, rightly, deduce that the Church had now finally “come to its senses” and baptized the sexual revolution.

McElroy creates a straw man in his use of Pope Francis’s remark that the Eucharist is not a “prize for the perfect” but “medicine” for the sick. The pontiff’s remark is, of course, a true statement. But who actually thinks this way, that is, views the Eucharist as a “prize for the perfect”? Who actually espouses such a Pelagian view? I don’t know one single Catholic—and I’ve known many in my sixty four years of existence—who holds that view. And, prescinding from whatever it is the Holy Father was trying to say, Cardinal McElroy employs it as a tool for advocating for open Eucharistic table fellowship, in particular for sexual sinners. Because, after all, who among is perfect? None of us. Ergo, all should be allowed communion no matter their moral status.

This flimsy argument allows McElroy to equate traditional sexual morality—and the Eucharistic discipline that goes with it—as a form of pharisaism that self-righteously seeks to “exclude”. Meanwhile, his own advocacy for the veniality of most sexual sins and for open table fellowship is presented as the “merciful” and properly “Christian” inclusive view.

But this is clearly contrary to both Scripture and Tradition. Saint Paul clearly disagrees, as he lists sexual sins as of a kind, along with other serious sins, that exclude one from the Kingdom (cf Gal 5:19-21; Eph 5:5; Col 3:5). This means that when Paul warns against receiving the Lord’s body and blood while in a state of serious sin, he is surely including sexual sins (1 Cor 11:27ff). But McElroy never references Paul in this regard, for obvious reasons, and never once addresses the fact that his views represent a radical novelty in the entire history of the Church going back to the apostolic era.

His use of straw man arguments against the traditional view gives the appearance of being mere rhetorical devices in the service of a set of conclusions in search of an argument. It would seem that it is the good Cardinal who is claiming that he has all the answers in advance, drawn not from the Church’s tradition, but from the sexual ethic of secular, Western Liberalism. Because if he was truly interested in honest theological discourse, he would not engage in such vacuous caricatures of the theological reasoning behind the Church’s traditional Eucharistic discipline. And if he was truly interested in positioning his views within the normative categories for Catholic theology (i.e. Scripture and Tradition), then he would do more than quote a few rhetorical, off-the-cuff statements from Pope Francis.

However, the problems with McElroy’s analysis goes beyond straw man caricatures and also involves glaring inaccuracies. For example, he claims the Church never treated sexual sins as grave matter until the 17th century: “For most of the history of the church, various gradations of objective wrong in the evaluation of sexual sins were present in the life of the church.” But this is not the case at all. All of the Church Fathers, including Augustine and Aquinas, viewed sexual sins as gravely sinful (albeit in varying levels of sinfulness, depending on differing elements in their moral object). It is true that, in the 17th century, we see the rise of moral casuistry and a reemphasis from the Jesuits—who had been accused of laxity in their theological approach to sexual morality—that sexual sins do indeed involve grave matter. McElroy apparently (he never cites a single historical source) concludes that is the first time the Church had so defined sexual sins, which allows him the rhetorical space to engage in his moral revisionism. But this is just so wrong on a historical level that it is actually painful to read from a Cardinal of the Church who one would expect to know better.

McElroy uses this faulty historical analysis (apparently rooted in a bad interpretation of Charles Curran’s analysis of the history of moral theology) to imply that we can now treat homosexual sex, in the main, as only venially sinful because prior to the 17th century matters were more open to such thinking. But how so? McElroy is clearly trying to put the fig leaf of tradition over his naked dissent from 2,000 years of clear teaching on homosexual sex as gravely sinful. (There is a reason why the Catechism states, very clearly: “Basing itself on Sacred Scripture, which presents homosexual acts as acts of grave depravity, tradition has always declared that ‘homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered.’” [par 2357]). And he then uses that fig leaf as cover for turning tradition on its head, accusing those of a more traditional view of violating the “ethos” of the broader Catholic moral tradition. It takes a lot of chutzpah to make such a claim, especially given the fact that his views on homosexuality are completely contrary to the entirety of the tradition.

A further inaccuracy is McElroy’s claim that only sins against the sixth and ninth commandments are “automatically” considered to be grave matter, while sins against the other commandments are not. The last time I checked my freshman year notes from “Moral Theology 101,” any deliberate act against one of the ten commandments involves grave matter. (And, again, the Catechism says: “Grave matter is specified by the Ten Commandments…” [par 1858]). Idolatry was considered as involving only a parvity of matter in the tradition? Really? And what of murder?

Is McElroy seriously asking us to believe that the Church has never considered idolatry and murder as “automatically” involving grave matter? Or gross disrespect for one’s parents? Or violations of the commandment to worship God on the Sabbath? Hasn’t the Church always taught that deliberately missing Mass on Sundays is a grave sin?

McElroy then goes on to list a series of sins that the Church, allegedly, does not “automatically’ consider to be grave sins. Among those he lists are spousal abuse, employee abuse, and abandoning your children. But the Church does indeed teach that these sins involve grave matter when they are at a level of abusiveness that causes grave harm. Therefore, McElroy’s argument here borders on the incoherent and deflects from the central issues at hand. Is sex outside of lifelong heterosexual marriage sinful or not? And if it is sinful (even if only venially so, as he suggests), then the best counsel is to avoid it, and not to treat it with a moral insouciance that sees it as “no big deal”.

McElroy’s treatment of the role of conscience is also so tendentious as to constitute an inaccurate description of its role in moral living. Space precludes me from analyzing this at length since it is indeed a complex topic. But suffice it to say that McElroy’s approach has more in common with overly subjectivist views of conscience than it does with the Church’s traditional approach. It also plays in the sandbox of modern notions of the therapeutic self, coupled with a rather oracular view of conscience as some kind of generator of self-made moral norms. The net effect is to reduce all moral decisions in the sexual domain to something wildly idiosyncratic, owing to my peculiar, unique, and “enormously complex circumstances”. McElroy does pay lip service to the importance of the Church’s role in forming conscience, but it rings hollow.

A final inaccuracy is McElroy’s rather breezy description of Christ’s pastoral approach as beginning with love, followed by healing, and only then followed by a challenge to do better. I call this “breezy” because it only describes some of Christ’s pastoral encounters but not all. Think of the story of Christ’s encounter with the rich young ruler, when Christ leads with the challenge—”If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor…and come, follow me” (Mt 19:21)—and not with “accompaniment”.

When the young man walks away, Christ does not go after him but turns to the crowd and issues a rather harsh assessment of the distorting effects of wealth on the soul. And what are the first words of Christ in his public ministry? “”Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Mt 4:17; Mk 1:15). In point of fact, in Christ’s earthly ministry the loving and healing often come simultaneously with the challenge of repentance. But in McElroy’s pastoral approach the challenge to repentance is bracketed as something onerous, even at odds with the loving and healing. Which bespeaks a fundamental belief that the challenge to repentance is not itself an act of loving mercy. Which means, as he himself says, that such a challenge is indicative of a cold, gnostic logic of a “law” divorced from mercy.

Finally, there is an aspect of this entire debate which is too much on the level of abstraction. And that is the effect McElroy’s words will have on same-sex attracted Catholics who are struggling to live out lives of sexual continence, in line with Church teaching. Not out of some slavish obedience to “rules,” but out of a recognition that the Church’s teaching is life-giving and truly liberating. But, according to McElory, that same teaching lacks mercy and imposes real pain on struggling LGBTQ people, the clear implication of which is that the teaching is false—at least in part, if not in whole. Where is the affirmation for such faithful same-sex attracted Catholics in anything McElroy has written? It is nowhere to be found, as if he finds it embarrassing, which leaves such Catholics hanging out to dry.

Since my original essay on McElroy, I have received numerous emails from same-sex attracted Catholics who want to live out the Church’s teaching, but who feel thrown under the bus by McElroy and his allies. As one person wrote to me, “I am surrounded by gay friends who are sexually active who mock me mercilessly as a sap and a fool for following the Church. And now they have more ammunition with which to mock me, as even a Cardinal of the Church calls the Church’s call to sexual continence as overly painful and burdensome.”

And what of faithful Catholic catechists, teachers, and priests, who have fought the good fight on this issue with compassion, but also with fidelity? Who have been persecuted for their views and who are often on an island in an ocean of angry dissenters, many of whom are in ecclesial positions of authority? Who must now deal with being accused of standing against the “new” moral paradigm of “mercy” in the Church? McElroy’s words will now be weaponized against them from people within their own Church and their position will now become untenable to the point of unbearable. Where is the accompaniment for such people?

“Well,” a friend remarked to me, “at least McElroy is starting a conversation we need to have.” I said to him, “Wrong. It is a conversation we have already had and do not now need to relitigate.” It is almost as if Veritatis Splendor was never written. But that is a conversation for another day.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.