Archbishop Charles Chaput, OFM Cap., who retired in January 2020 as Archbishop of Philadelphia, sat down with The Pillar this week to talk about the future of the Church, a Jay-Z song he likes, and his new book, “Things Worth Dying For.”

Below are excerpts from The Pillar’s conversation with Chaput, which have been edited for length and clarity. A full version of this conversation can be heard here.

The Pillar: Archbishop, your new book is “Things Worth Dying For.” It is your fourth book, is that right?

That’s correct. It’s my last one also.

I’ve said that three times before, but I mean it this time.

Archbishop, the book is a reflection on the things that mean the most in life, at least as you see them. It is a meditation, as you write, from a vantage point where “the road of life in the rearview mirror is a lot longer than the road ahead.”

It’s centered on knowing the meaning of our lives, but also the meaning of our deaths, and understanding our mortality.

And it’s interesting that the book has come out during the pandemic, when a lot of people are taking stock on what their lives were before, and on what they might be going forward. You obviously didn’t plan that timing. Do you think it’s providential?

I actually began the work before the pandemic began.

I think this is the first time in my life, since the Vietnam War, where people have been actively afraid of dying or afraid that someone in their family would die.

I mean, it happens every day in terms of people getting sick and having elderly parents or whatever, but in terms of a lot of people worried about the possibility of dying when they’re actually younger and healthy, this is really the first time since the Vietnam War that that’s been a common experience, I think.

Forever young

The Pillar: Fear of death probably exists unspoken a lot of the time, I think, even before the pandemic.

It seems that’s even a fear for believers, but especially for those without an expectation of what’s to come.

Yeah, that’s right.

One of the things that I say in the book that I think is very interesting is that there are three characteristics of human beings that are not common with any other part of the created world, at least that we know:

Sometimes animals watch over [the body of] a dead animal companion for a while after it dies, but they don’t bury the dead.

And it’s been part of our human tradition to do that from the very beginning. And so there’s something about being human beings that leads us to take death seriously.

And actually, you know, I think a quality of human beings is the fact that we also want to conquer death. We want to see there’s hope beyond the grave. And that’s so much a part of our process of caring for the dead. Is it?

So we believe that that death is just a step into the next life, which is the gift of eternal life in our Christian understanding.

Our fight against death is part of our fight against Satan himself.

I think we all want to live forever. That was the lyric of a song that I grew up with and which I liked very, very much:

Jay-Z actually came up with a version of it maybe 10 or 12 years ago. That was also very good:

So you and President Obama both have Jay-Z prominently in your iPods is basically what you’re saying.

Well, I don’t know if I have anything more of Jay-Z’s in mine than that one song, but I do have that one song.

Family Life

The Pillar: Archbishop, in “Things Worth Dying For” you write about your parents a great deal.

I was struck early in the book, when you write about the image of your father kneeling at his bed at the beginning of the day and the end of the day. It seems your parents were a witness of faith for you.

That’s true.

You know, I don’t know that people kneel at their beds to pray at the beginning of the day and the end of the day at all anymore, but it was very common back in my time for parents to do that.

My parents were very good Catholics. They knew their faith very well, even though neither one of them had more than a high school education. My mother was a nurse, but back in those days you didn’t have to go to college to be a nurse. She just had to get a nurse nursing certificate. And my father had an embalming certificate because he ran a funeral home.

But they knew their faith very well and passed it on to us, by example as well as by word, and they would have been hugely scandalized if we acted against the faith or said anything against the faith, because they were natural believers and sincere believers.

They weren’t daily Mass attenders, and they didn’t run for the parish council or anything like that, but they never would miss Mass on Sunday. We went to confession as a family every two weeks. And I was really grateful for that example.

You talk about your parents as you move into a chapter on the love and life of a family — you write about the power of families to form virtuous individuals, even saints.

You also recognize that families have had a strange year. Families have grown a lot closer, and in a lot of ways they’re more connected to each other, but they’ve also struggled with isolation and financial calamity, and many with mental health challenges. And some sociologists have been talking about that there’s probably going to be a sort of pandemic baby bust.

What does this challenging year say about families, and even what God might be saying to American families right now?

You know, I don’t really understand the so-called “baby bust.” We used to joke that whenever there was a weather calamity and people were forced to be at home together, there would be a huge burst of new life — rather than the fewer births, it’d be more births. So where that comes from, I don’t know.

I think married couples certainly have a greater insight into what’s happening there than those of us who are celibates, but it’s certainly not good: Not good on the natural level, as well as the supernatural level. It may be a sign that we lack confidence in the future.

One of the things that I’ve also noticed about the pandemic is that people are actually tired of being together.

I know that many people have said, “Oh, it was wonderful, we have more time for our children and for each other.” And I think that’s true, maybe in most cases, but there are other cases where it’s really been very, very difficult because people just get tired of one another.

I don’t think it’s natural for us to always be in the same space for such a long period of time. I think that we’re meant to be creative in the world, around us and to be outside the home as much as inside the home.

We haven’t been able to make decisions apart from the reality we’re living in. So we’ve hopefully tried to make the best of it, but I don’t know how to explain that. I really think it’s strange.

In our family, the sense of being thwarted, as you say, is acute. We want to impart to our kids a sense of apostolic mission as a family, and to look outside of themselves more, and especially to love the poor, and that’s become more difficult.

One of the most beautiful examples of that is here in Philadelphia: St. Katherine Drexel.

St. Katherine Drexel’s mother died when she was quite young and her father remarried. And the woman he married was an extraordinary Catholic. And they would invite the poor to share meals in their home every week. And that’s one of the ways that both he and his wife passed their faith and generosity to their children was by not just helping the poor outside the home, but inviting the poor to their home, on a regular basis. And I think that people are hesitant to do things like that today…but that would be an extraordinarily good way to educate your children on the Christian necessity — not just a possibility, but the necessity — of loving the poor.

You write about prayer as the essential center of family life. And while that’s true, some parents just aren’t sure how to pray with their children. How can families actually learn to pray together?

Well, you know, my parents never did spontaneous prayer with us. I don’t think they ever prayed with each other in that way. We did pray together at the beginning of every meal — we wouldn’t have begun a meal without saying grace, and my mother and dad gave an example to each other, as well as the kids, by publicly praying by themselves.

When we were kids, like before we were five years old, my parents would take turns going to Mass on Sunday, so they wouldn’t have to have the kids with them to be distracted during Mass. That isn’t done today; everybody goes to Mass together today.

But the reason I’m saying these things is we didn’t do the kind of things that were seen as kind of romantically families bringing together. But we did learn the importance of prayer and the consequences of that in the good example that my parents gave.

I encourage parents to pray together in a way that their children can see them praying, and then to teach their children to do the same.

You know — my family did pray the rosary together when I was very young, but that never went over very well. My sister and I, well, we rebelled against it a lot and tried to escape it.

I think praying a decade of the rosary together probably is a better thing — a better way to start praying together as a family.

We find in our house that much more than a decade turns into a weird mix of praying and fighting with our kids to be quiet—

That’s right. Yeah. We have to be realistic about what works, you know.

It’s always better to do a little bit of something well than to do a lot of something poorly. And unfortunately in the Church, we sometimes think that we please God by just doing more, when we really would please God more by doing less, but doing it well — sincerely and with focus and concentration.

The Church

The Pillar: You talk in the book about the challenges the Church faces, and the way in which many people are no longer learning or practicing the faith. You even tie that to the way the Church is perceived in civil society. Those things lead me to questions about renewal in the Church’s life.

People don’t use the term “new evangelization” as often as they once did, but I wonder where you see places of renewal in the Church’s life.

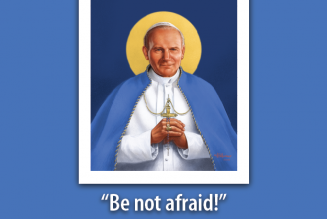

Well, I do see the springtime of the Church that Pope John Paul II spoke about is still taking place, but it’s just on a much smaller level than we had hoped for or expected.

I think we thought that that meant the whole of the Church would re-embrace Christ with a new kind of vigor and enthusiasm.

But, you know, I would say without a doubt, that the young people today who become serious Catholics are much more serious about it than the young people who were Catholics in my day — much more serious. It’s harder to be serious about it because the Church is much more criticized today than it was in those days. The sins of the Church are much more publicly known than they were in those days, but nonetheless, we find many, many young people committing themselves to Christ and to the community of his followers: the Church.

And so I still have a lot of hope for the Church.

I don’t think we should cling to the images we have of how the Church is going to look from the past, because it’s going to look very different than the past.

And I think one of the problems we have today is trying to maintain that past heritage in the face of decreasing numbers and decreasing abilities financially to support it. And that’s dangerous because if you use all your financial resources maintaining the old decaying institutional structures of the Church, you don’t have any resources to put into the creativity that’s really necessary to be evangelists in the 21st century.

So I don’t know what we can do about it.

I live in Philadelphia where we have lots and lots of churches that would be cathedrals in any other parts of the country, but here they’re just ordinary parishes, and in parts of town where you have very few Catholics anymore. And [those parishes] just have huge problems in terms of the structures of the buildings. And we’re putting so much money and attention and creative priestly ministry into those dying expressions of the faith.

And if they die, people are going to panic and say, “Well, the church is falling apart.” Well, the Church is certainly different in size, but is she falling apart? And has the Church really ever been more than a small group of serious believers, even with — at different times in history — a huge number of people on the periphery? I don’t know…

It has been characteristic of your ministry to invite groups of diverse perspectives — new movements, lay apostolates, religious orders, groups like the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, into the dioceses you have led. What are the criteria by which you have decided what kinds of movements or groups to open the door for?

Two things. One is zeal. I’m a sucker for people who are zealous and enthusiastic. And the second is orthodoxy, I’m a sucker for them too. And you know, the movements that are really successful are those that are simultaneously orthodox and zealous, and nothing else ever works.

Nothing else ever works, ever.

Archbishop, in “Things Worth Dying For,” you talk about the reform of the Roman Curia, which you compare to a kind of Renaissance court. You call for a simpler view of the papacy. I appreciate that idea. At the same time, there is a movement in the Church to decentralize authority in order to undermine or supplant doctrine – you can see that in the efforts of the German synod. What is the balance between simplifying the Roman Curia, and ensuring it is empowered to preserve and teach Catholic doctrine?

I’m not against the centralization of Church authority. I think it’s necessary in a world as large and complex as our world is. And instant communication requires a central authority that can hold the group together or people will go off in different directions, as you say.

But many of the forms of the Roman Curia are remnants of the Renaissance — even the clothes that people wear and the titles that we use, like “Eminence” and “Excellency.” Peter and Paul didn’t refer to each other in those kinds of ways.

Now I’m not against some of that symbolism because I think it can be helpful. But it is just helpful, It’s not essential.

And you know, I also think that we’ve come maybe too far in terms of seeing the papacy as kind of the measure of ordinary Church lives throughout the world. The pope is the one who makes the final decision when there are struggles in the Church regarding true faith and morals. He is the one who leads the Church to unity, And I think that’s absolutely essential, or the Church falls apart,

The pope isn’t the pastor of the world — he is the universal pastor in the sense that his authority is everywhere. But there can be ways of being the Church in Africa that the pope wouldn’t understand because he’s not from Africa. And so the way of doing the Church in Rome will be Roman, but the way of doing the church in different parts of Africa, for example, would be somewhat, if not seriously different — as long as there’s unity of what we believe and how we act in terms of faith and morals and deep respect for the role of the pope in being the arbiter of those kinds of things, when there’s disagreements.

John Paul II was a hero to many people who are my friends — he really was the bishop of the world. I mean, he traveled so much and I think many bishops modeled their episcopal life on him….But in that sense, I don’t think John Paul was a model of the way the Bishop of Rome should have to act. I don’t think somebody like Pope Benedict would have retired, maybe, if he didn’t see himself as having to kind of follow the path that John Paul II had, because it required so much energy that he didn’t have at his old age.

I think it’s important to find a balance — the heart of the papal ministry is to keep the Church in unity with the teachings of the apostles, which of course are the teachings of Jesus. And as long as the pope is doing that, he’s doing his job.

On friendship

The Pillar: Archbishop, you end your book with a chapter on friendship. Why was that the note on which you chose to conclude?

You know friendship is the heart of our relationship with Jesus.

He says, “I no longer call you servants, I call you friends” and “There’s no greater love than to lay down your life for a friend.”

And Jesus showed us how to do that, you know, he’s an example of that.

Those of us who are Christians are supposed to be disciples of Christ — and since he was willing to die for us, we should be willing to die for him and learn from him how to die for other people.

And friendship has been a really important part of my life. When I’m discouraged, I look at friends not only for support, but for example. In fact, I’m the kind of person that needs their example more than I have the need for personal support. I need the example of other people struggling with the same issue that I’m struggling with.

And I think that friendship is the future of Christianity, because that’s the way you have genuine conversions: By meeting people who are believers and then becoming part of their life and being infected with the virus of grace, it changes our lives and makes us a different kind of people, who are friends of God.

One of my best friends died a year and a half ago. And he was a good faithful Catholic, but our friendship began by being fishing buddies and then developed into just a lifelong relationship — we were the best of friends.

Thank you, Archbishop, for talking with us about “Things Worth Dying For.”

Well, thank you for the attention to the book. I like this book better than any of the other books I’ve written. So I hope people find it helpful.

God bless you.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity