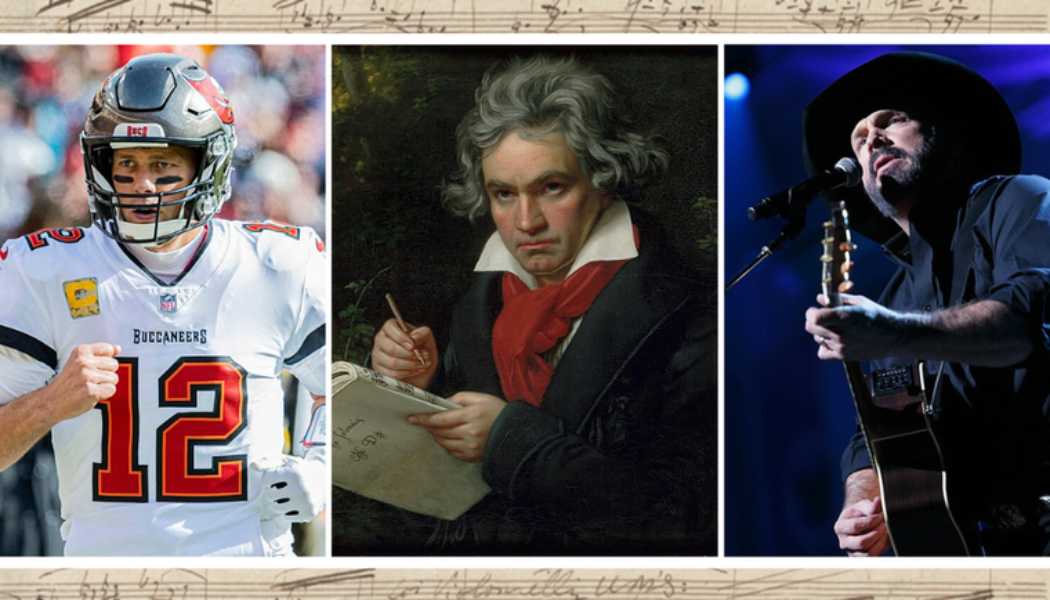

It was an inspired choice for the Vatican to hold its World Meeting on Human Fraternity in the same week as the bicentennial of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, a sublime anthem and prayer for universal brotherhood.

From the sublime to the … well, less sublime; Garth Brooks and Tom Brady will be on hand, too.

Brooks will sing at the closing concert in the atrium of St. Peter’s Basilica on Saturday. It is possible that Pope Francis will give Standing Outside the Fire the same Holy Spirit gloss which Pope St. John Paul II gave to Bob Dylan’s Blowing in the Wind at the 1997 Eucharistic Congress in Bologna.

It is unlikely that Vatican organizers, when asking Brady to participate in a sports roundtable entitled “Competing in Mutual Esteem,” knew that he would arrive less than a week after his live “comedy” roast on Netflix, which was three hours of wall-to-wall profanity and degrading humor. “Condemning in Mutual Obscenity” would have been an apt title.

The two American celebrities are joining dozens of leaders in 12 fields of endeavor, from economics to medicine to the arts. A long list of Nobel Peace Prize laureates will produce a declaration on human fraternity.

The fraternity summit is the second such the Vatican has hosted and builds upon two signature initiatives of Pope Francis — the 2019 “Declaration on Human Fraternity,” signed in Abu Dhabi, and the 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti. It has been a priority for the Holy Father to promote means to build fraternity in a time of polarization, hostility and war.

The priority of culture has deeper roots still, in Pope St. Paul VI’s esteem for the arts and John Paul II’s understanding the priority of culture. John Paul II established the Pontifical Council of Culture in 1982. As a young man, formed in the theater and epic Polish poetry, John Paul chose to study philology at university. As an adult, he saw in Polish culture the resources to resist tyranny and defend human dignity. As pope, he taught that every culture, at its deepest level, gave an answer to the question of God.

In 1991, John Paul merged the Secretariat for Dialogue With Non-Believers into the Council for Culture. It was his conviction that the Church should not see people in terms of what they did not believe, but rather through what their various cultures held to be good, true and beautiful. In light of such cultural encounters, the Church could then propose Jesus, the Way, the Truth and the Life.

Cultural and fraternal encounters can be fraught, such as witnessing Brady arriving just days after reveling in the worst of American popular culture. It remains true, though, that culture also gives expression to the highest ideals and noblest aspirations.

Such is the case with the Ninth Symphony, one of the great human achievements in history, given that Beethoven was almost completely deaf when he composed it from 1822 to 1824. The program does not indicate what role the Ninth will play at the fraternity summit, but its fourth movement, the Ode to Joy, is the world’s anthem of brotherhood. It is the official anthem of the European Union. At the Olympics in the 1950s and 1960s, when West and East Germany competed together, their “national” anthem was the Ode to Joy.

The first three movements of the Ninth explore various themes, as symphonies usually do. But the fourth movement rejects these options, and the human voice enters. That was a novelty for composers when the Ninth made its debut in May 1824.

Oh friends, not these tones!

Let us raise our voices in more

Pleasing and more joyful sounds!

Beethoven’s insight was that, despite the glory of God reflected in the natural world, the human voice is needed for proper praise.

“Man is the cantor of creation,” said the late Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, reflecting ancient Jewish wisdom. Astonishingly, the Ninth was not the only item on the program the night of its debut. Beethoven also included three movements from his Missa Solemnis (“Solemn Mass”). The Ninth was intended to be framed by sacred music, if not considered sacred music itself. In the encounter between culture and faith, the distinction is not always clear.

The Ode to Joy is a poem by Friedrich Schiller from 1775 that Beethoven thought well captured the joy of true harmony among brothers, a harmony that was a divine gift.

Can you sense the Creator, world?

Seek him above the starry canopy.

Above the stars He must dwell.

Be embraced, millions!

This kiss for all the world!

Brothers! above the starry canopy

A loving father must dwell.

The Ninth as a whole, and the Ode to Joy within it, was quickly recognized as one of the great masterpieces in the history of music, but it became more than that. The 19th and 20th centuries, riven by wars in Europe, both hot and cold, made ever more profound the desire for fraternity, for harmony, for peace. The Ninth was the highest cultural expression of that aspiration. It was the deep cry of a culture rooted in the Bible that had lost its way.

The Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9, 1989. Beethoven’s countrymen were united once more. Just weeks later, on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, first in West Berlin and then in East Berlin, the Ninth was performed under the baton of Leonard Bernstein. The orchestra and choir were made up of Germans West and East, as well as nationals of the four former occupying powers of Berlin: United States, United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union.

At the end of those historic Christmas concerts, Bernstein remained impassive, as if in deep reflection or prayer. He was exhausted with the emotion of the occasion. His life work was now complete. He would be dead within the year.

The maestro knew well the near-mystical force of the Ninth, not just in Beethoven’s genius but in its sheer biblical power. The Ode to Joy, in Bernstein’s estimation, was a direct echo of King David himself, crying out praise in Psalm 133: “Behold, how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity!” It took up the cry of Isaiah, that the swords would be beaten into plowshares (2:4). It rejoiced in the coming of the Prince of Peace — hence the decision to stage the German concerts for freedom at Christmas.

The struggle for fraternity is the aboriginal quest of mankind, from Cain and Abel to the promise of Psalm 133. The consequence of the Fall is that brother turns against brother.

The quest for fraternity seeks to reverse that, by the grace of God to be sure, but also as a fruit of true culture, the sublime expression of which Beethoven gave to the world two centuries ago.