I have written before about why we need to eliminate the idea of a “Golden Age” of Christianity, a time when the church was nearly perfect, an era that we just need to imitate if we want to create healthier churches today. And, after a few minutes reflection, most people accept that every generation had its flaws and foibles. We learn from them not because they were perfect but because they walked before us and modeled how to live faithfully in the midst of a horribly broken world.

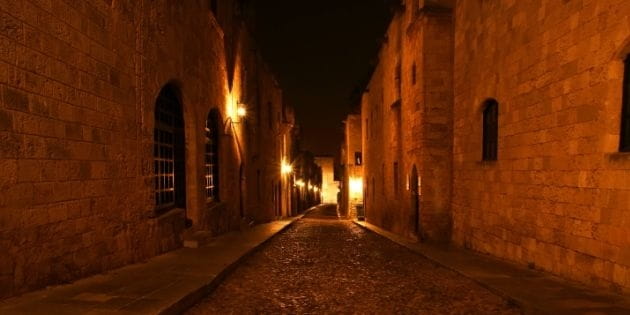

But many still want to hold on to the Golden Age’s evil twin brother: the Dark Age, an age where the church was so fallen and its understanding of the truth so twisted that we have virtually nothing to learn from those who lived through those dismal days. An age when the lights went out, leaving only darkness.

For most Protestants, the Dark Age was not just a particular generation, or even an entire century. No, we have our sights on something bigger, blacker, and more tragic: the wasteland of medieval Christianity. A thousand years lost in the dark void between the bright lights of the early church and the Reformation.

Even in my church history classes, after I’ve spent weeks arguing that we need to study each period of church history fairly, recognizing that every generation has its shares of both flaws and successes, I find students struggling to believe that there’s anything worth learning from the church in the Middle Ages. And that’s tragic. It’s somewhat like saying that there’s nothing to learn from those Christians who lived in the roughly thousand years between Charlemagne and today.

A Mirror for Today

There’s no question that the church in the Middle Ages faced daunting challenges: widespread biblical illiteracy, pervasive cultural syncretism, a society steeped in violence, incredible disparities between rich and the poor, church leaders often more concerned with power, influence, and prestige than ministering to their flocks, political leaders more than happy to co-opt the church for their own purposes, and pastors who were often ill-equipped to deal with these pressing difficulties.

Sound familiar?

A time like that would challenge even the most faithful Christian. So we shouldn’t be surprised to discover that Christians in the Middle Ages often struggled to identify the right courses of action and draw the right conclusions. But look closely enough at the Middle Ages and you’ll see a church struggling through many of the same issues that face us today.

The Middle Ages were not a time in which faithful Christians virtually disappeared. But like today, it was a time in which faithful Christians faced daunting challenges, sometimes wisely and sometimes foolishly.

If we can learn from those who walk beside us, surely we can learn from those who went before.

Faithful through the Darkness

Karl Barth once lamented the idea that we should ever write off entire periods of the church as completely lost. According to him, it’s always safer to assume that Jesus continues to work faithfully with his people in every age than to believe the opposite.

“The assumption that Jesus Christ did not altogether abandon his Church in this age, and that, notwithstanding all the things that might justly be alleged against it, it is still in place to listen to it as one listens to the Church–this assumption would always seem to have a very definite advantage over its opposite. In any case we certainly need very weighty reasons if we decide to drop, as it were, the Church of any period, adopting that attitude of contemplation and evaluation from outside and no longer listening seriously to its voice.” (Church Dogmatics I/1, 377)

Granted, this particular quote has to do with the church in the years following Constantine’s conversion. But the logic holds for medieval Christianity as well. Can we ever believe that Jesus abandoned his people in any age? And if the church continued to be Christ’s people, how can we think that it would be profitable to silence their voices and ignore their hard-earned wisdom?

Rejecting the Remnant Mentality

Just for fun, I once created a chart of church history from a Baptist perspective. It’s a caricature, but it tries to capture the common perception that there are large periods of time in which only a very small remnant of the church retained the truth, everyone else had fallen into apostasy and unfaithfulness.

And that’s usually the best people can say about the middle ages. Maybe a few people held to the truth, but only a few. The rest were completely lost.

The danger of the remnant mentality lies in identifying the faithful remnant with those who are most like you, as though faithfulness comes in only one flavor, thus missing the opportunity to see and be challenged by forms of faithfulness that might be unfamiliar to you.

None of this means that we should be blind to the failures of the church in the Middle Ages. Of course there were failures. Of course many were unfaithful. That is true of every age. But many, maybe even most, still strove for faithfulness in the midst of a broken world.

Like Elijah, we look out from our modern mountaintop, lamenting that all have fallen before the medieval Baal. And like Elijah, we need to be reminded that God has always been at work with his people, yesterday and today. And as always, there are more who have not bowed the knee than we believe and fear.

Marc Cortez is Associate Professor of Theology at Wheaton College, husband, father, & blogger, who loves theology, church history, ministry, pop culture, books, and life in general. You can read more from him at marccortez.com.