This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

When Nick Chancey was a boy in West Virginia, he didn’t have much time for Christianity. He spent the occasional Sunday hiking into the woods with his father to offer a cup of milk and a handful of quarters to forest fairies. His dad kept a small Buddhist statue at home, and dabbled in Native American spirituality and “druid and Celtic stuff,” Chancey told me. “It was not uncommon for the Baptist preacher in his Sunday best to show up on our doorstep and for my dad to cuss the guy off the porch because he was saying we were going to hell.”

Chancey’s views started to change in college. A friend invited him to the Catholic hub on campus, where he immediately felt welcome. One night, at the home of a Catholic family, his hosts suggested watching an episode of a 2011 documentary series called Catholicism. Until then, Chancey said, “I had seen Jesus as one of two extremes: either a really angry guy who was judging people and condemning them to hell, or he was this domesticated hippie figure.” The series, by contrast, presented Jesus as “mysterious; his own followers were amazed and afraid.” Chancey devoured the 10-part box set. “It all made sense to me. What do you do with that? It was kind of scary. There was only one pathway forward.” Chancey converted to Catholicism. Now he works for the Church in his home state, overseeing programs in youth and young-adult ministry.

The creator of that documentary is today’s most effective Catholic evangelist, and the most controversial—the 65-year-old bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester in Minnesota, Robert Barron. More films followed Catholicism, as well as books, study courses, podcasts, and YouTube videos with nearly 200 million views. Barron published them all under the aegis of his digital empire, Word on Fire Catholic Ministries. In the Catholic English-speaking world, he has more social-media followers than any clergyman except the pope.

Now is an unlikely time for a Catholic ministry to grow. Fewer and fewer Americans embrace any religion, and the U.S. Catholic Church is shrinking. Yet Word on Fire continues to expand. When I visited its headquarters in Rochester earlier this fall, Barron told me that he senses an “extraordinary hunger for God” in America, but “beige Catholicism” won’t satisfy it. That’s his term for the Church that many American Catholics have known in the 60 years since Vatican II: simplistic and relevant homilies, felt banners, acoustic guitars—all meant to make the 2,000-year-old faith fit in with contemporary Western culture.

Barron, who is always in clerical dress and ready to quote the ancient Church fathers, has no interest in fitting in. His uncompromising presentation of the Christian story—and his willingness to discuss it with polarizing figures such as Jordan Peterson and Ben Shapiro—resonates especially among young men. To fans, Barron is convincing a new generation that Christianity is not the faded wallpaper of the West but a compelling, countercultural message. To critics, he has forged a cult of personality and cozied up to culture warriors for the sake of clicks.

The bishop’s ambitions extend far beyond YouTube. He wants to build a real-life network—priests and laity gathering in Word on Fire centers around the country. More than that, he is scouting a future for Christianity: a Church that embraces the internet as an evangelizing tool, refuses to assimilate to mainstream culture, and welcomes the young men who are beginning to outnumber women in the pews. Driving this mission is a simple but risky bet: that many seekers don’t want a faith that is easy and accessible. They want something difficult and strange.

When I entered the plain, glass-front building that houses Word on Fire’s headquarters, I wasn’t sure I was in the right place. Then I saw the picture wall of patron saints: the Catholic televangelist Fulton Sheen; the teenage French nun St. Thérèse of Lisieux; Pope John Paul II. Posters for The Godfather and A Man for All Seasons lined the hallway.

Movies launched Barron’s YouTube ministry. In 2007, when he was a young priest in his hometown of Chicago, he posted his first video: a review of the depiction of evil in Martin Scorsese’s The Departed. At the urging of his mentor, Cardinal Francis George, he began broadcasting Sunday homilies, dialogues with atheists, and more. Four years later, Barron released Catholicism. In 2015, Rome transferred him to serve as an auxiliary bishop in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, then, in 2022, to head the diocese of Winona-Rochester.

A priest named Steve Grunow oversees Word on Fire’s daily operations; Barron spends most of his time tending to his diocese. But if any intellectual, politician, or social-media personality with a following wants to talk, Barron is game. He has spoken at Facebook’s headquarters and addressed Congress and members of the U.K. Parliament. Online, he has talked about morality and the meaning of life with people ranging from the progressive Representative Ro Khanna to the conservative activist Christopher Rufo.

But he generally steers clear of politics—and rarely misses a chance for a theological deep dive. “Dumbed-down Catholicism was a disaster, pastorally,” Barron, who has a doctorate from the Catholic Institute of Paris, told me. “If you don’t think that young people have serious questions that need answers,” he added later, “then you have not accompanied many young people.” When Google invited him to speak at its headquarters in 2018, he lectured for an hour on Thomas Aquinas and the intellectus agens, “the restless, seeking, never satisfied mind.”

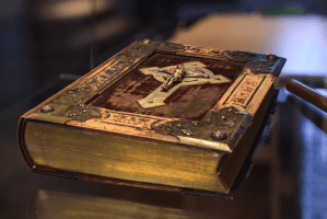

Barron plumbs topics that confound the secular world, such as transubstantiation and the Shroud of Turin. He wants to prove that Catholicism is not just another lifestyle choice based on the Golden Rule. The Word on Fire bookstore sells artwork meant to remind viewers just how unsettling the Christian story is: the Holy Spirit cascading onto the apostles in a torrent of lava; a pack of wolves ripping into the unresisting body of a lamb.

If the ultimate source of meaning is “Jesus crowned, but with a crown of thorns, reigning, but reigning from a cross,” Barron said recently, “then we’re the weirdest religion around.” He aims to invert worldly assumptions and break through our “crusty self-absorption”—his phrase for Dante’s mindset at the start of The Divine Comedy, one of his favorite books. He frequently admonishes his audience: “Your life is not about you.”

This is not the message that he got as a young Catholic. “To be frank about it, when I was in the seminary, it was more of a feminized approach,” he recalled. “We did a lot of sitting in a circle and talking about our feelings.”

The early years of Barron’s media ministry coincided with the heyday of the new atheists, who won over many young men with books such as Christopher Hitchens’s God Is Not Great and Sam Harris’s The End of Faith. But they also inspired a renaissance among the faith’s defenders. Like Barron, many took to YouTube with a cerebral, confident style that appealed to men. Justin Brierley, a Protestant podcaster who has been a professional apologist for almost two decades, noticed that the crowds at apologetics conferences “did not look like the population in church on Sundays. Eighty or 90 percent were male,” he told me. “In a funny way, the new atheists helped bring men back to church, because the Church had to respond.”

On YouTube, according to Word on Fire’s data, more than 60 percent of Barron’s viewers are men. YouTube users in general skew male, and his followers on Facebook and Instagram are more evenly split between men and women, but YouTube is the heart of his ministry. “The Millennial male who is listening to Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson, all those podcasts and YouTube channels—now, through Bishop Barron, they are being exposed to a fresh take,” Brierley said. “The era of them just listening to Sam Harris’s take on religion is over.”

For at least 300 years, clergy have fretted about how to get men to go to church. Women’s dominance in the pews has been one of the most reliable sociological facts of the Christian world. But that’s beginning to change. Among the college-educated, men are now slightly more likely than women to attend church every week. The political scientist Ryan Burge analyzed the numbers and found that 69 percent of male college graduates younger than 40 claim a religious affiliation, compared with only 62 percent of women.

Some pundits argue that as gender norms shifted and women started outnumbering men in universities and the white-collar workforce, men have grown resentful and nostalgic for patriarchy—so they seek it in traditional religion. J. D. Vance is the country’s most famous Catholic convert, and the story of his rightward shift might seem like a template for all Gen Z and Millennial men interested in Christianity.

But framing this trend as bitterness and backlash misses the deeper reality. Many young men feel unmoored—lonely in a time of weakening social institutions, unsatisfied and overworked by an accelerating professional rat race, alienated by political tribalism. “Men my age, we don’t have the social organizations that our fathers or grandfathers did,” Torrin Daddario, a Barron fan who converted to Catholicism from a Protestant background, told me. “We’re adrift.” Over the past decade, both the left and the right have tried to fill the void with morality tales that treat unfettered individual freedom as sacred and split the world into victims and oppressors. Those stories are getting stale.

Darren Geist was drawn to Barron’s ministry when the atheistic worldview he grew up with stalled out. After graduating from Princeton, he moved to Sierra Leone to work for UNICEF, where he focused on women’s health and children’s rights. He found himself debating with Christians and Jews about how to justify the universal human rights he sought to protect. He stuck to nonreligious arguments. “But I came to the conclusion that these have a weak foundation,” he told me, “or a foundation borrowed from Christianity.”

Eventually Geist went to law school and joined a firm in New York. The job left him feeling “intellectually dead,” he said. “A lot of us are in these jobs that are soul-sucking, intellectually draining, and menial. Even when they are elite-sounding, they are menial jobs. We don’t feel fully alive.” During long commutes, he started listening to Jordan Peterson—whose lectures weave together Jungian psychology, the quest for purpose, and the Bible. Then he discovered one of Barron’s podcasts. (This is a common story: Peterson does not call himself Christian, but his fascination with the biblical narrative—not to mention his taste for menswear emblazoned with Orthodox icons—compels secular listeners to take a closer look at Christianity. Algorithms then guide them to Barron.) Geist realized that he had “been fed this milquetoast version of Christianity, not the deep, rich version that’s actually there.” His spiritual journey took some surprising turns, but Barron played a major role. Geist entered the Catholic Church in 2020.

Joining a religious community, submitting to its rules, and learning its traditions is hard. I could find no data to indicate how often Barron inspires listeners to put down their phones and start going to church. Progressive critics are skeptical that he’s much better than podcast bros like Joe Rogan at guiding young men toward “ethical heroism” and Christian virtue. After the actor Shia LaBeouf—once a self-described “Sam Harris, TED Talk, Christopher Hitchens guy”—began investigating Catholicism, Barron invited him onto his show. The liberal Catholic press criticized Barron for failing to confront LaBeouf about past run-ins with the law and accusations that he abused former girlfriends. (Those who watch the interview might see it differently. Although LaBeouf has said that “many of these allegations are not true,” he readily confessed to Barron that his egotism had inflicted “pain and damage on other people.”)

If Word on Fire makes a point of embracing troubled men, perhaps the ministry bears a burden of extra vigilance—especially in a Church with an extensive record of abuse. In 2022, the ministry fired a producer after investigating allegations of sexual misconduct in his personal life. (The former staff member has denied the allegations.) Several employees resigned, citing a “boys’ club” culture.

Although Barron swears off the culture wars, some of his conversation partners have made their names trolling the left. “What I want to say to Barron is, ‘You’re participating in this culture of grievance. That’s the problem; that’s the complicity,’” Michael Sean Winters, a writer for the National Catholic Reporter, told me. He warned of the risks of an “online existence where the algorithms favor anger and easy hostility, not wisdom and truth.”

Barron receives criticism from the right as well. When he says—echoing Pope Francis—that “we have a ‘reasonable hope’ that all will be saved,” conservatives hear heresy. In their view, he is too supportive of liberal priests and does not spend enough time condemning homosexuality. Eric Sammons, the editor of Crisis Magazine, called Barron “an uncritical, enthusiastic defender of all things Pope Francis” who follows “only the letter of orthodoxy, not its spirit.”

If both the left and the right find fault with Barron, the feeling is mutual. “I don’t like Catholic progressivism. I never have. I don’t like ‘rad trad’–ism. I never have,” he told me. The Word on Fire bookstore sells editions of Vatican II’s declarations and decrees, as well as The Pope Benedict XVI Reader—because Barron believes that it’s a mistake to pit the supposedly liberal “spirit of Vatican II” against Pope Francis’s “conservative” predecessor.

Ultimately, concerns about ideology bother Barron’s detractors less than his taste for empire building. His tweeting, TikToking, and branded merchandise don’t sit well in a Church that stresses humility and hierarchy. On the webpage advertising leather-bound, gilt-edged Word on Fire Bibles with commentary, Barron appears first on a list of contributors, ahead of the Church fathers. His name and picture are everywhere—like in “Bishop Barron’s Word on Fire Institute,” the ministry’s hub for online classes and communities. The bookstore offers a volume called The Theology of Bishop Barron. “He speaks as if he is the face and voice of Catholicism in the U.S., and he’s not,” Michael Sean Winters said. “He’s the bishop of a tiny diocese in Minnesota.”

This is one of the paradoxes of Christian history: Entrepreneurs with healthy egos tend to make great evangelists for a faith founded by an impoverished, self-denying carpenter. Like any of the Church’s evangelistic enterprises over the centuries, Word on Fire’s success is hard to imagine without its opportunistic and occasionally immodest founder.

Barron’s long-term goal is to grow the online communities affiliated with Word on Fire Institute—about 25,000 people—into a religious order that operates across the country. “I’d like it to continue after me,” he said. “That’s why I’d like it to be institutionalized, both at the lay level and the clerical level.” He envisions Word on Fire centers in major cities “where people can receive instruction and inspiration,” modeled in part on Opus Dei, an organization that has dozens of centers across the United States, and which some view as secretive and controlling.

He waved off such concerns: “The last thing I want is to be cultlike.” Barron’s vision is bigger. “The whole idea is to evangelize the culture,” he said. “It’s not to turn inward, into some kind of self-protective cocoon. It’s to go out to the world and engage it—creatively and enthusiastically, with panache and intelligence. This is what I want to do.”