I take it as a privilege to be a forty-one-year-old Catholic theologian in the year 2023. Born in 1982, only twelve years after the promulgation of the reformed rites of the Second Vatican Council, I am in the main sympathetic to those who are often called Vatican II Catholics. My theological education benefited from a close reading of primary sources both ancient and modern. I learned from professors at Notre Dame and Boston College who were involved in teaching and research during the Council. I was initiated into a theological style that was dynamically orthodox in its modality, standing within the Catholic Tradition but willing to read and encounter thought outside of the theological center. Fundamentally, I perceive my own vocation as receiving and developing the post-conciliar theological proposal around the liturgical act and thereby fostering the kind of liturgical participation that generates a social, pedagogical, and cultural renewal in late modernity.

Attending to my own sympathies is no mere biographical exercise. Rather, it is a way of situating the fundamental claim of this essay: Vatican II Catholics—that is, those who came of age immediately after the Council and the decade that followed it—are wrong to treat the return of interest in Eucharistic adoration as a retrograde rejection of the Council. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament is on the rise precisely because the lay faithful understand that if they are to make their lives sacrificial offerings, to receive the Eucharistic presence of our Lord at Mass, and to contend with the many demands of a frenetic existence, they need an encounter with Christ that extends beyond the Mass itself. What we are experiencing is an authentic ressourcement emerging from the faith of the People of God. To dismiss this is to fall prey to the desk-bound theology that Pope Francis warns against in Evangelii Gaudium (§133), which raises theological quibbles rather than attending to an authentic exercise of piety that is a post-conciliar retrieval of a contemplative stance before the Eucharistic mystery.

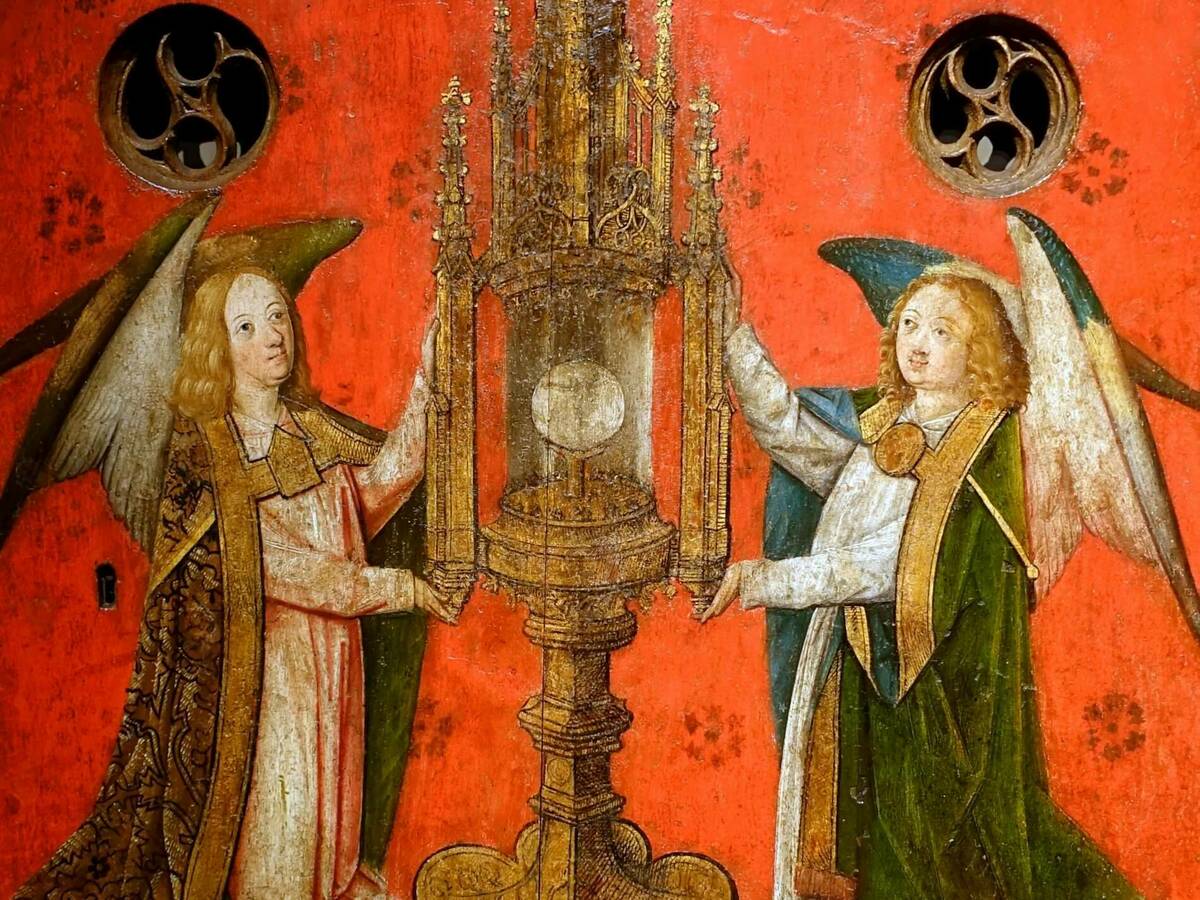

What follows, therefore, is an exercise addressed to colleagues and mentors alike who are suspicious of adoration. Rather than continue to fume against the rise of adoration, to express dismay that the Eucharistic Revival in the United States is obsessed with images of monstrances, perhaps our vocation is to think alongside the faith of the Church and discover anew the gift of spending time before the Eucharistic Lord. To begin this work, we must first examine our own biases against adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

Objections of the Eucharistic Adoration Detractors

The reasons that many post-conciliar theologians are suspicious of adoration of the Blessed Sacrament are easy enough to rehearse. You have likely heard or read them even in Catholic publications with a national reach. The Eucharist is meant to be eaten, not looked at. Eucharistic adoration is passive and not active. Jesus is present among the poor, not only in the Eucharist, so why put so much focus on the Host? The Eucharist is not meant to be treated as an object, and therefore, we should not have processions or spend so much time looking at the Eucharist—instead, we should participate in the sacrifice of the Mass.

I rehearse these objections not to make light of them. I have learned too much from St. Thomas to not take a friendly objection as an invitation to develop subtle distinctions.

Objection 1: The Eucharist Is Meant to Be Eaten, Not Looked At.

True, our most profound encounter with the person of Christ comes through the act of eating. Medieval Catholics, such as Albert the Great, knew this (and it is why he spends an inordinate amount of energy attending to the relationship between digestion and the Eucharist in his On the Body of the Lord). If you only go to Adoration, and you never receive Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, you are doing it wrong.

But let us be rational about this: Who is skipping Mass, not receiving the Eucharist, but spending hours attending Eucharistic adoration? Can you imagine it? Yes, I am willing to spend hours in the presence of Jesus Christ, but I will never, ever receive him at Mass. If you meet this person, be sure to introduce me.

But there is a deeper problem with this objection. It presumes a rather limited vision of the human person, inattentive to how the Eucharist involves the totality of the senses. In receiving the Eucharist, yes, I am united to the Lord and to my fellow Catholics through the love of Christ poured into my heart. Taste and see the goodness of the Lord (Ps 34:8). But is not the gaze itself a mode of communion?

After all, when I look upon my children with a love suffused with gratitude, I am not saying that fatherhood is reducible to perception. I know that I still need to take them to choir, feed them, and put them to bed. Mutatis mutandis, Eucharistic adoration involves the totality of our senses, and therefore pausing before the presence of Jesus in the Eucharistic mystery, gazing upon the Host in love, is a way of growing in a deeper appreciation of his presence.

Objection 2: Eucharistic Adoration Is Passive and Not Active.

This objection, I presume, depends on a rather limited understanding of passivity and activity as actions of the human person. In this sense, passivity is simply sitting and watching something, not taking part in it. Activity, on the other hand, is embodied and thereby personal involvement. I passively watch a play; I actively perform the same play.

The problem with this claim is that it is again a fundamental misunderstanding of human perception as a whole. In reality, everything we do is always both active and passive at once. Let us return to the example of gazing upon my children. When I look at my children, am I being passive? Should I not get up and play some games with them?

Contrary to this impoverished account of human activity, what if all human action is always at once active and passive alike? I must choose to look at my children, meaning that I must choose not to do something else. Looking is therefore a supreme activity.

Concurrently, this act of gazing is regularly accompanied by the act of remembering a moment in the life of my child or spontaneous moments of gratitude (and often enough, worry). Yet, all along, I am receiving this perception of my children and the accompanying insights. Is such looking really passive, at least, in the way used above?

In truth, Eucharistic adoration and the Mass alike involve an array of both passive and active moments operating next to one another precisely because they are actions of human beings, who in any act of perception are always active and passive simultaneously. In sum, the liturgical gaze is an active passivity and a passive activity.

Objection 3: Jesus Is Present Among the Poor, Not Only in the Eucharist, So Why Put so Much Focus on the Host?

It is important to remember that Jesus Christ is present to us in a number of ways, not exclusively through the Eucharistic species. Jesus Christ is present in the created order, which consists of logoi of the Logos, words of the Word that should lead us to praise and adoration. Jesus Christ is present in the Scriptures, as he speaks to us hic et nunc. Jesus Christ is present in the assembly’s worshipful praise at Mass; the Church is, after all, Christ’s Body, and when the members sing, the Head sings too. Jesus Christ is present in the poor, and it is the task of every Christian to worship our Lord through the works of mercy and commitment to justice. Nonetheless, these presences of Christ cannot erase the careful distinction that Sacrosanctum Concilium (§7) made between these manifold presences and the distinctive presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Christ is present under the Eucharistic species most especially (maxime).

Read rightly, we are not talking about competing presences. Jesus is present in the Scriptures, so do not give too much attention to the Host. He is in the poor, so why all this attention to transubstantiation? Rather, because he is present in a hidden way under the signs of bread and wine, we are formed to look more closely to perceive his hidden presence elsewhere. Eucharistic presence, therefore, may be a way to lead the Church into a deeper commitment to worshipfully attending to the hidden Christ manifest in our brothers and sisters on the margins. We focus on Eucharistic presence because it provides the paradigmatic encounter with the hidden God that enables us to perceive this hidden love in all things.

Objection 4: The Eucharist Isn’t Meant to Be Treated as an Object, and Therefore, We Shouldn’t Have Processions or Spend so Much Time Looking at the Eucharist—Instead, We Should Participate in the Sacrifice of the Mass.

As any reader of St. Thomas’s Summae knows, there is often an objection in which there is a fundamental agreement at least as the terms are treated. It is true that the Eucharist should not be treated as an object, a magical talisman that the Church schleps about in the world to show that God dwells among us (and not among you heathens). Further, the tendency to speak about the Eucharist exclusively as the Host means that many Catholics have still not understood that the Eucharist is also sacrifice and communion.

The Eucharist is the entire sacrificial act of the Mass that culminates in the great oration of the Eucharistic Prayer. To participate in the Eucharist is the great actio that involves the flesh and blood sacrifice of ourselves as a return gift of love to the Father through the Son in the unity of the Holy Spirit. This sacrifice orients the Church toward deeper communion with the triune God and one another. Because we eat and drink the Body and Blood of Christ, we are called to the very same charity with all those called to the Supper of the Lamb. Acknowledging all this is pivotal to a maximalist Eucharistic vision.

Still, it is faulty to presume that all acts of Eucharistic adoration and Eucharistic processions are objectifying. Idolatry is a threat in the Christian life, and our worship can always become a way of controlling God. Acknowledging this fact means that we must be critical about our worship, attentive to the dark places in the human heart where sin can make even the most splendid of gifts into the sham of vice. But strictly speaking, the whole point of the doctrine of transubstantiation is that we are not worshiping an object (a piece of bread) but the very person of Christ, the Eucharistic Lord who gives himself to us under the signs of bread and wine.

A Constructive Response to the Detractors

It is one thing to attend to objections, it is another to offer a compelling and constructive narrative. The remainder of what I will say here seeks to offer such a vision. It builds this vision out of the four objections above.

Response 1: Eucharistic Adoration Is a Saving Encounter with the Person of Jesus Christ, and Therefore It Is Meeting the Person of Jesus Who Comes to Heal and Transform Me.

The language of encounter has become ubiquitous in magisterial teaching. In fact, the encounter with Jesus Christ as the basis for Christian existence is discernible in each of the three most recent pontiffs. In a particular way, that encounter unfolds in the Eucharist.

But how is Eucharistic adoration an encounter with Jesus? In a recent piece in America Magazine, Msgr. Kevin Irwin states that strictly speaking we are not encountering the body of Jesus but the body of Christ, “the entirety of the mystery of the totality of Christ: his whole earthly ministry and also his suffering, death, and resurrection and ascension to the Father’s right hand to intercede for us in heaven. The Eucharist is the real presence of this body of Christ, not Jesus only.”

Fair enough! On one level, this is a traditional claim, one discernable in St. Thomas Aquinas. The Lord who becomes present on the altar is not present as in a place. His presence on the altar is different from the experience of the disciples in the Sermon on the Mount. The Lord came to be present in all those places precisely because it is the risen and ascended Lord who comes to us, transforming, through the power of the Spirit, bread and wine into his personal presence.

But on the other hand, does this mean (as Irwin claims) that one cannot (without risking heterodoxy) call the Eucharistic presence on the altar, Jesus? Must one only speak of the Body of Christ? Irwin brings up magisterial references, noting that texts from Sacrosanctum Concilium and Paul VI do not refer to the presence of Jesus but of Christ. He also attends to the way that the Roman Missal rarely (he says never, but a quick search of the Missal reveals otherwise) speaks of Jesus without modifiers signifying his glorified state.

This is one of those moments where a certain desk-bound theology (one that I believe artificially separates the terms Jesus and Christ as if the ascended Lord left behind his historically marked flesh for a cosmic identity apart from his embodied and therefore historical existence), I fear, defeats the work of evangelization that the three most recent pontiffs have called for (not to mention that it does not attend to the data presented by the piety of the people themselves, a point raised by Roberto Goizueta in his Christ the Companion). The desire of the human heart is to encounter Jesus, the Word made flesh, the splendor of the Father, whose saving mysteries are available to us. Men and women want to be called to the Supper where Jesus gives himself to us hic et nunc.

Pope Francis has no problem speaking about how we are made contemporary to the work of Jesus. Quoting from his sublime Desiderio Desideravi:

No one had earned a place at that Supper. All had been invited. Or better said: all had been drawn there by the burning desire that Jesus had to eat that Passover with them. He knows that he is the Lamb of that Passover meal; he knows that he is the Passover. This is the absolute newness, the absolute originality, of that Supper, the only truly new thing in history, which renders that Supper unique and for this reason “the Last Supper,” unrepeatable. Nonetheless, his infinite desire to re-establish that communion with us that was and remains his original design, will not be satisfied until every man and woman, from every tribe, tongue, people, and nation (Rev 5:9), shall have eaten his Body and drunk his Blood. And for this reason, that same Supper will be made present in the celebration of the Eucharist until he returns again (§4).

The Pope refers to the work of Jesus (without qualifier). In the Eucharistic act, the human person encounters Jesus Christ’s desire to celebrate anew that Supper for the sake of bringing all men and women into this communion of love. It is Jesus who gives himself to us, uniting us to this saving mystery. Jesus’s desire, as the flesh and blood God-man, is that which brings about our desire in the first place.

Adoration, for this reason, is an encounter with the person of Jesus. Hidden under the signs of bread and wine, the God-man desires to once again dwell among us. In fact, the hiddenness is the very mode in which Jesus’s desire reaches out to the human person. We are free to respond, to meet him with a return gift of love in the silence of the adoration chapel.

In point of fact, this is what men and women want in adoration. When many liturgists condemned the Eucharistic processions and adoration that substituted for Mass (for a time) during the pandemic, they forgot something about the Eucharist. The lay faithful who go to Mass are looking to meet the Lord there, to make sense of their joys and sufferings in light of his presence. The Lord comes to heal us, to dwell among us in the Eucharistic act. Yes, we can objectify such presence, forgetting the eschatological register intrinsic to the Eucharist. But that is not the fault of a Eucharistic devotion that is seeking an encounter with Jesus. It is mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

More simply, knives can cut meat intended to feed your family. Knives can also murder. We do not get rid of knives because they can be misused. We learn to use them aright.

Response 2: Eucharistic Adoration, Therefore, May Be Loved Most of All by the Poor, Those on the Margins, Rather Than Those Who Are Ordained Clergy.

It is common to note that the pendulum tends to swing to extremes. If pre-conciliar liturgical practice erred on the side of extra-liturgical devotion, then the post-conciliar period has erred on the side of dismissing such devotion. If the liturgical rites are the apex of piety, then everything else must be considered as a relative good. But here is the problem: the Roman Missal and the Liturgy of the Hours, despite their manifold benefits, cannot attend to the fullness of our religious desires.

I get this, especially as a layman, who is a father. I attend weekly (and ideally daily) Mass. I regularly pray the Divine Office. I run a Center for Liturgy. I am all in. Still, the heart has desires that the official liturgical rites of the Church cannot know (or fulfill). It is hard to be a full-time administrator, a full-time dad, a full-time husband, and a full-time professor. At times, I need something more than the Mass can offer me.

Now, I happen to work in a building where there is a chapel, where our Eucharistic Lord is constantly present. To sit before this presence is a way to speak one-on-one with Jesus about all that I am going through. I hand my will over to him. I do not dictate the terms of the conversation, bringing along the many books and spiritual exercises that I might use to avoid the intensity of the encounter. I come with just me.

I fear that we in the religious elite (and I include professors and priests alike) have forgotten the religion of the poor. Most of us in the Church are not clergy or recipients of a doctoral degree in liturgy. We are ordinary men and women trying to make sense of our complicated lives. We sit before the Tabernacle, crying out to Jesus, because we know he listens to us.

Of course, we should form such persons to understand that this gift can be offered at Mass too. But I have spent too much time over the last three years with ordinary Catholics who love Eucharistic adoration to believe that the Mass can do everything for them. They need this time alone with Jesus Christ. They are, in fact, taking up the tradition of Eucharistic devotion discernable in Mechthild of Magdeburg, Mechthild of Hackeborn, and Gertrude the Great of Helfta.

The attraction to Eucharistic adoration is based therefore on a form of poverty, both material and cultural, that we share as men and women abiding in late modernity. As Jan-Heiner Tück writes describing Eucharistic eating and adoration alike:

To the extent that we allow ourselves to take a moment with Christ, the Other, our life can itself become other, different. Everyday life, which appears unspectacular, mundane, and distant from God in its routine, can itself be transformed by consciously pausing before the signs of God’s nearness par excellence. Contemplative Eucharistic piety always responds to the fact that in the moment of receiving the host . . . the immeasurable is hardly to be measured, that Jesus Christ, who in his life and death did everything for us, gives himself right here in sacramental form . . . Precisely when life is marked with hectic patterns and prevalent activism, pausing for a moment can be a salutary interruption of everyday life, leading us to see the everyday with new, transformed eyes” (A Gift of Presence, 314–315).

For the person who works all day at the factory, who cares for the sick in the hospital as a nurse, who frets over feeding their kids, moments of Eucharistic adoration are not quaint exercises of piety. They are encounters with the Lord, who help all of us to see the presence of the hidden Jesus in the rest of our lives.

I will state here that the ordained, in particular, may struggle to understand what I am talking about. The clergy have worries, which they bring to the Lord. But until you worry about feeding your kids or losing your job, one does not know how lonely it can all be. The only thing you have left to do is to give it over to Jesus, who as the Eucharistic Lord can transform it all. Is not part of our current synodal process listening to the piety of the people, discovering the faith of the Church lived out among the People of God?

Response 3: Eucharistic Adoration Serves as a Necessary Reminder to the Church That the Telos of the Liturgy is Holiness Rather Than more Liturgy.

The liturgical renewal precipitated by the Council is a good that I will defend to my dying breath. But in the post-conciliar period, there has been a temptation to read the post-conciliar documents in such a way that the liturgy becomes the totality of Christian piety. But the goal of the liturgy is not more liturgy. It is holiness.

In his recent re-reading of Hans urs von Balthasar’s Eucharistic thought, Jonathan Martin Ciraulo offers a salutary irruption pertaining to this point. He writes, “It is holiness that functions as an instrument that is properly attuned to measure the appearance of Christ in the Eucharist.”[1] As such, the liturgical rites of the Church do not guarantee holiness. They are not magic. Instead, they are one of the many “instruments” by which the Christian orients his or her life toward sanctity.

Now, let me be clear. Eucharistic Benediction and processions are in fact liturgical acts. They are present within liturgical books approved by the Holy See. Still, the personal and contemplative act whereby we dwell before the Lord is not strictly speaking a liturgy. But it also fulfills the liturgical end.

The critique of such personal dwelling is that it is too individualistic. Yes, it is tempting to adore the Blessed Sacrament in a way that is attuned only to individual piety. But concurrently, all prayer does involve the person, the individual who is engaged in prayer. Communities in the liturgy pray. But communities are made up of individuals with an interior life, who must also pray. They pray not only to experience the liturgy but to encounter the living God.

Ironically, this was the precise concern of both Jacques and Raïssa Maritain in their Liturgy and Contemplation. The liturgical act must be ordered to holiness. But every act of contemplation should be ordered toward this higher end, union with the Beloved.

Eucharistic adoration, therefore, is situated betwixt and between liturgy and contemplation. Yes, it is liturgical, the highest exercise of the virtue of religion. But it is also peculiarly personal. It taps into the desires of the human heart, poured out before God.

Enter any adoration chapel in the United States and you will see people sharing their flesh-and-blood lives with the living God. They are seeking union with God. They are doing so by going to weekly Mass, but they are also doing so in a personal way. The liturgical and the non-liturgical life are necessary to seek the ultimate telos of Christian life: beholding the Beloved in saecula saeculorum.

Response 4: Eucharistic Adoration Is a Spiritual Practice That Slowly Moves Away from Spectacle Toward the Hidden Encounter with Love Itself.

One should recognize that Eucharistic adoration, although good for all the reasons listed above, can become a form of idolatry. Such idolatry is especially prevalent when adoration is taken up in a culture dominated more by spectacle than the hidden gaze of love.

The Lord becomes present in the Eucharist, yes. But it is a hidden presence. Medieval Christianity highlighted this hidden presence through contemplative imagery and music alike. The Lord came to dwell upon the altar, and an altarpiece featuring the Annunciation invited worshippers to slowly recognize and delight in this fact. Music tended to function in a similar mode, inviting people to see more than they might have initially.

But the practice of adoration today too often falls into the trap of spectacle. There are lights. Drums. The distinction between a Taylor Swift concert and adoration is often marginal. An encounter so spectacular that the affections must bend the knee.

But the hiddenness of the encounter may be that which is most healing of all. He comes, but in a way that we cannot immediately recognize. He comes, asking most of all for the return-gift of self freely given (rather than manipulated through perception and affections alike). Critics of adoration, I fear, are reacting to that which is tangential to adoration in the first place.

If we learn to recognize the hiddenness of presence, then the result of adoration will be a more profound attention to the presence of Christ especially among those who are on the margins. There is no spectacle in feeding the hungry or thirsty. There is just the person, with all their flesh and blood materiality. And still, our Lord tells us in Matthew 25, there he is. He is made present through the poor.

A constructive Eucharistic theology will eschew spectacle for the subtlety of a loving encounter that trains vision to meet the hidden Lord in bread once bread and wine once wine. We have to admit that at least some of the adoration events that take place at youth conferences are at risk of falling into such idolatry if young people are not led from this spectacular encounter to the central insight that this very same encounter happens in a simple country church when an elderly woman bends the knee before the tabernacle. The lights and the worship music are accidental to the encounter rather than intrinsic to it.

After all, as St. Thomas reminds us: where the senses fail, faith alone suffices. The gap between perception and desire is precisely how Eucharistic mysticism works. You do not see, but if you love, you see more.

Conclusion

I began by noting that I am happy to be a theologian trained in the post-conciliar era. But I am simply confused by the way that adoration has been treated by members of the immediate post-conciliar generation, who ought to be attentive to the faith of the local Church. Adoration, as I hint throughout this thought exercise, is not ancillary to a post-conciliar Catholicism. To adore our Lord in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist is to carry out the very mission of the Church presented in Sacrosanctum Concilium (§1):

It is of the essence of the Church that she be both human and divine, visible and yet invisibly equipped, eager to act and yet intent on contemplation, present in this world and yet not at home in it; and she is all these things in such wise that in her the human is directed and subordinated to the divine, the visible likewise to the invisible, action to contemplation, and this present world to that city yet to come, which we seek. While the liturgy daily builds up those who are within into a holy temple of the Lord, into a dwelling place for God in the Spirit, to the mature measure of the fullness of Christ, at the same time it marvelously strengthens their power to preach Christ, and thus shows forth the Church to those who are outside as a sign lifted up among the nations under which the scattered children of God may be gathered together, until there is one sheepfold and one shepherd.

Adoring the Eucharistic Lord would invite us to meet the Lord anew in a world to which the Church pilgrims through history. And to see in this world the presence of Christ who comes to play, as Gerard Manley Hopkins states, “in ten thousand places.” I really hope that such detractors would cease eschewing adoration and instead uphold the gift of this practice for the late modern human person, seeking to understand the deeper desires leading to its adoption by Catholics both young and old.

[1] Jonathan Martin Ciraulo, The Eucharistic Form of God: Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Sacramental Theology (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2022), 151.