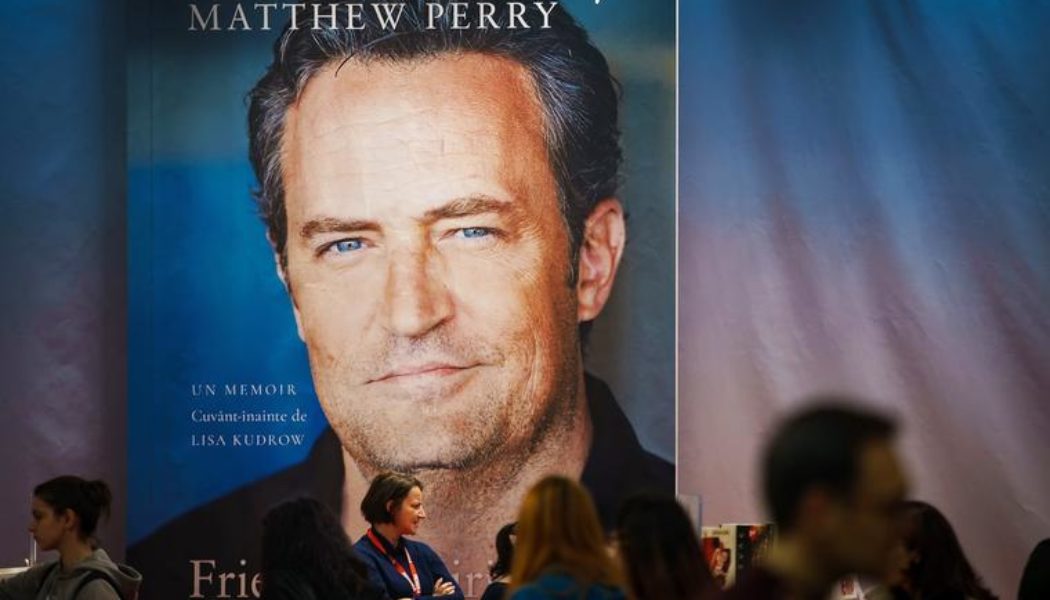

Have you ever read a book that takes you in and captivates you, stirs your heart and mind and, for whatever reason, just won’t let you go? I just finished reading Matthew Perry’s new memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, and I honestly can’t stop thinking about it.

Oh, I know, it’s not Chaucer. It’s not even the latest mass-market “Christian living” read. It’s not about a saint or the Pope. The story’s protagonist is a bit of an anti-hero for most of it. And the subject matter is admittedly dark — a lot of drugs, some references to unchaste sexual relationships, and a goodly dose of coarse language.

So why did I read it?

Well, truth be told, I was a bit of a Friends enthusiast back in the day. I remember watching the pilot as a young teenager when it first aired in 1994, and faithfully tuning in each week thereafter. (I’d even record the episodes onto VHS tapes, to pass around the next day to kids at school who weren’t able to catch it the night before. Yes, I was a nerd. But this was before streaming and on-demand viewing, so someone had to do it!) And really — if you weren’t watching Friends in the 1990s, were you really living? (Confession and further nerd alert: I’m an unapologetic superfan of a number of ’90s sitcoms. I quote Seinfeld on a near-daily basis. And I still think David Hyde Pierce is one of the most talented comedic actors there is. Sorry, but NBC was killing it back then, and I was there for it.)

But anyway, I loved Friends. Still do, really, even though I haven’t watched an episode in forever. (And, truth be told, I don’t let my own kids watch it. Somehow the 1990s were different. Or something.) And Chandler Bing, played by Matthew Perry, was my favorite character. He was funny, self-deprecating, hopeless, and deep down I think he wanted to be a good guy. By the end of the series of course he’d won and married the beautiful girl he loved, started a family and found happiness.

Matthew Perry’s own life story, however, has been a bit more complicated.

The actor has battled a very serious drug and alcohol addiction for decades, and throughout all but one of the 10 seasons he was on Friends. His colon even eventually blew up as a result. (He wound up in a coma.) Chillingly, he remembers how he got on his knees and prayed to God once, three years before getting the Friends role: “Please, God, make me famous. You can do anything you want to me. Just make me famous.”

He believes God made good on that prayer, in both respects.

Perry writes that he was actually never much of a partier, but used drugs and alcohol so he could feel “okay,” like he was enough. Because he felt like he was never enough. He talks about being abandoned by his father — and then later being abandoned by his mother, who was always working — as a small child. He says he has all these holes that he’s tried to fill with fame, women, alcohol and drugs. He decides that he chased and achieved all the wrong dreams. He can’t believe he ever broke up with Julia Roberts. He laments wasting much of his life and not having a wife and children.

But he also had a religious experience once in his kitchen, when he was essentially at rock bottom, where he firmly believes he encountered God. (This occurred right after he’d prayed, “God, please help me. Show yourself to me.”) He credits this encounter as the miracle that allowed him to achieve sobriety for the next two years. He calls himself a seeker.

The truth is that I have rarely (if ever) read a memoir so brave, so wise and so honest about the broken human condition. If there’s one thing you can say about Matthew Perry, it’s that he is not at all deluded about his need for healing and redemption. He knows he’s messed up. He knows he’s made some extremely bad decisions and can’t fix them.

But he also knows that God has kept him alive for a reason. That he should be dead, but he miraculously survived, and he wants to spend the rest of his life helping people. And the main thing is that he hasn’t, and won’t, give up.

It may seem like a strange choice for Lenten reading, and Perry’s book is probably not for everyone. But the human and spiritual elements he touches on are unexpectedly profound. Perry’s doubts about his self-worth, for example, reflect a struggle common to many. Who am I? Who did God create me to be? What is human dignity, and how do I live up to it? How do I heal this rupture of self, of wholeness? What role ought sexuality play within love? Which dreams are worth chasing? And, finally, a question for the ages: What does it mean to live a good life?

The book, to me, was oddly reminiscent of a Southern Gothic novel in its ability to use and explore darkness in order to expose light and truth. The Catholic author Flannery O’Connor, arguably the queen of the genre, once said, “I use the grotesque the way I do because people are deaf and dumb and need help to see and hear.”

That can only be even more true today than it was back in 1960.

Of course if you’ve ever read any of O’Connor’s works, which I can’t recommend highly enough, then you know precisely just how dark they are, replete with quirky characters like the Bible salesman who seduces a woman in order to steal her wooden leg. (Do yourself a favor and go read her short story “Good Country People.” You won’t regret it!)

But Flannery O’Connor’s sheer brilliance, aside from being just a darn good storyteller, lay in the way she subtly and artfully wove themes like the human need for mercy, grace and redemption through each and every story. “There is something in us, as storytellers and as listeners to stories, that demands the redemptive act, that demands that what falls at least be offered the chance to be restored,” O’Connor once wrote.

Matthew Perry’s memoir, perhaps above all else, demands the redemptive act. Each and every page reflects a humble plea for restoration — the cry of a man who knows, knows, he is broken, and unable to put the pieces back together himself. Conversely, the reader too longs for healing and resolution, for God to reach out and rescue Perry from his plight. I couldn’t help but think of Jesus suffering on the cross for these very things, but also for the sins of pride in those of us who, like myself, too often prefer to believe that we are not so very broken. Matthew Perry is, like the rest of us, on a journey, and I hope he keeps seeking, and asking the hard questions about life and love and truth. There is hope — so much hope — in Jesus, and in the sacraments, and in the very notion of redemptive suffering.

When I picked up Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, it was really just because I like a good memoir, and because it was written by one of my all-time favorite actors from days gone by. (You know, the days when I had a Friends poster up on my bedroom wall, and rocked the iconic “Rachel” haircut — which in hindsight, by the way, was not a great look for my thick, naturally-wavy hair. I guess we couldn’t all be Jennifer Aniston. But we tried.)

Little did I know, though, that Perry’s book would instead turn out to be a deeply spiritual read, strangely well-suited to Lent, and such a painfully beautiful testament to the triumph of the human spirit and, ultimately, the need for and power of Jesus Christ. I’m glad I read it.