Happy Friday friends,

Front and center of the news this week has been, for obvious reasons, the situation in Afghanistan, and I have some thoughts about that. But also an urgent crisis is the situation in Haiti, which remains in ruins following last week’s earthquake, compounded by a tropical storm.

To that end, I just want to remind you that, as JD announced in his newsletter on Tuesday, this week we are donating the first $10 of every new subscription to The Pillar to Mission to the Beloved, a Catholic apostolate run by Haitians and for Haitians.

So if you have been thinking about joining us and supporting our work, please consider making this the week you decide to do it.

Quick links

First, some good news, at least prospectively.

A lookback window for filing lawsuits over historical cases of abuse has closed in New York state. The window in the statute of limitations was created by the 2019 Child Victims Act, opening in August of that year and set to run for twelve months. It ended up running for two years, with the state government granting extensions following the coronavirus pandemic.

There is certainly the hope that the legislation, which paved the way for thousands of lawsuits to be brought against Catholic dioceses and Church institutions in the state, will allow a measure of closure and healing for historical victims.

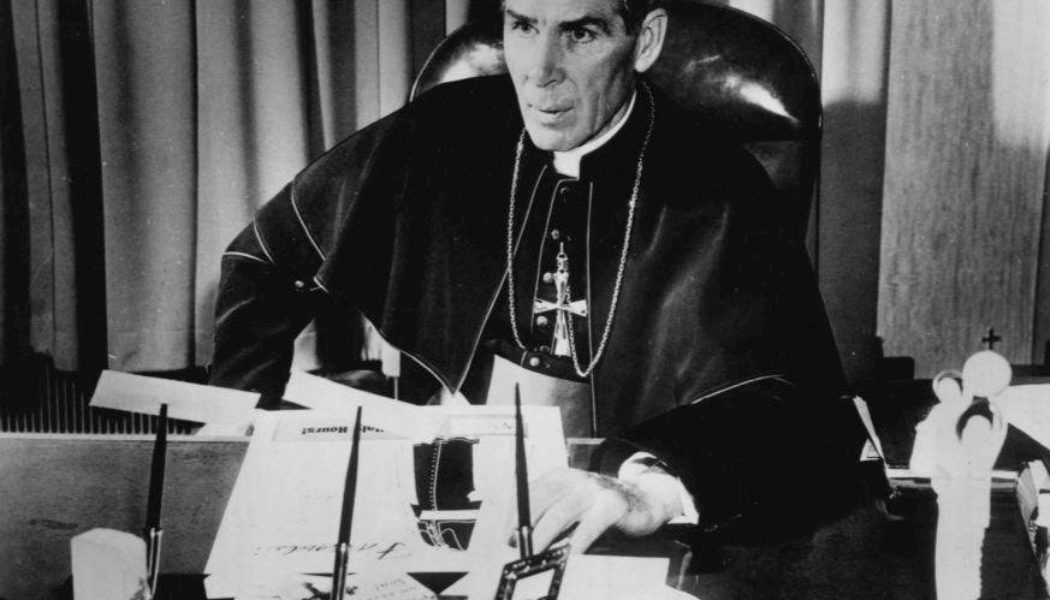

While stressing that they had no reason to believe Sheen had ever acted inappropriately, the diocese voiced concern that some claim or question could be raised about the handling of priest personnel issues during his time there, given the civil lookback window.

—

Local dioceses across the country, indeed across the whole Church, are soon set to kick off the first round of meetings which will slowly percolate up to the next meeting of the synod of bishops in Rome in two years time.

The synod on synodality is not something everyone in the Church is looking forward to; previous synods were often characterized by grand expectations of doctrinal and disciplinary reform and by sometimes fractious exchanges over what synodal documents would or wouldn’t say.

__

Elsewhere in the news this week was the resignation of a Brazilian bishop, after a video emerged on social media which seems to show the bishop engaged in what one would traditionally call self-abuse, while on a videocall with another man.

You can read the whole sad story here.

Bishop Ferreira has been previously investigated by Church authorities, it turns out, over accusations of both sexual misconduct and the mishandling of accusations of abuse of minors by priests in his diocese. On both occasions he was cleared after arguing that he was the victim of a smear campaign by “conservative” elements in his own diocese.

The case echoes that of Bishop Gustavo Zanchetta, who has now left his Vatican post to face trial in his native Argentina on charges of sexual harassment and abuse, and who survived initial complaints about his conduct (including evidence from his own phone) by blaming the machinations of his political enemies.

Both those cases are part of a broader trend in which episcopal misconduct has been apparently flagged to Church authorities and then dismissed after bishops claim they were the victim of political framejobs.

You can read his assessment here.

—

And finally, Church courts have been much in the news in recent months, not least because of the financial trial taking place in Vatican City. But keeping your Rotas straight from your Apostolic Penitentiaries can be a little tricky.

Our hollow world

Our country this week has been consumed with the still-unfolding debacle of the U.S. government’s withdrawal from Afghanistan.

We have all seen, to our shame and horror, the images of men falling from the sides of military planes as they take off, of women dragged from their cars and beaten, of children – babies even – being handed across crowds and through barbed wire.

Alongside these images of hopeless desperation, we have seen also the comically obtuse insistence of our government officials and elected leaders that they are “watching” the unfolding horror wreaked by the Taliban whom, we are told, must conform to Western liberal standards as they retake the country and impose their brutal vision for society.

“I think they’re going through sort of an existential crisis about do they want to be recognized by the international community as being a legitimate government,” said President Biden this week, before going on to concede that they probably care more about their religious beliefs than they do about courting the approval of the diplomatic twitter corps.

At least from the footage I have seen, it is not immediately apparent to me that it is the Taliban having an existential crisis about its values and commitment to them in the light of international scrutiny.

Over 20 years in Afghanistan, America built many schools, paved many roads, staffed many hospitals, and ‘secured’ much territory. But, in the final reckoning, it failed to build a nation. Why? Some have blamed the inevitably dependent kleptocracy which grew up around a government which has now fled into exile. And sure, the fragility of the government structures put in place in the past two decades has been laid punishingly bare.

But perhaps the real reason for America’s failure to build a new nation in Afghanistan is its failure, perhaps necessary inability, to build a new society there.

In the postmodern, postliberal West, we tend to conceive of nations as embodiments of civil architecture. Democratic elections, civil rights and liberties, economic freedom — these have become, in the minds of many, synonymous with the very concept of our “values.” We see them as more than just the structures we use to create an ordered space to live according to those values.

But, as a casual glance across our domestic landscape will show, we no longer have anything like a consensus on what those values are, where we get them, and to what end they are actually ordered — and we haven’t for some time.

We are, as many have observed, a cultural tree increasingly cut off from the Christian roots from which it grew, the roots which insist that human flourishing is found in God and lived through the self-sacrificing love of the other.

As a result, when proposing novel concepts like “freedom” and “democracy” in other parts of the world, we are left proffering strange fruits without the seeds to make them take root and grow anew, still less resist the Taliban’s brutally compulsive alternate vision.

We have long since lost sight of what, and to whom, our society is meant to be ordered; the result has been atomization, and the exaltation of the self vs the other.

It is that orientation which underpins the catastrophe in Afghanistan, and also our domestic dysfunction, in which all our interaction is reduced to the assertion of rights over and against the other — the unborn, the unwell, the indigent, the immigrant.

Into this void of common value and mutual love, the Church is compelled by her founding and nature to speak. Some have taken to indulging the fantasy of a political order governed by the authority of the Church, rather than a society shaped and formed by the faith she professes. But this, too, demonstrates the same interior hollowness which failed to build a nation in Afghanistan, as Cardinal Sarah observed in a recent article on the the Church’s liturgical wars:

“The anguish of imminent danger is the seal of barbaric times,” wrote the cardinal. “Without a sacred foundation, every bond becomes fragile and fickle.”

“Some ask the Catholic Church to play this solid foundation role. They would like to see her assume a social function, namely to be a coherent system of values, a cultural and aesthetic matrix. But the Church has no other sacred reality to offer than her faith in Jesus, God made man. Her sole goal is to make possible the encounter of men with the person of Jesus.”

The Church has a moral order, a governing structure, a social character, but all of these flow from her evangelical character, and are sustainable only to the extent that they remain rooted in her mission to announce the Good News.

But, as Catholics, we too have adopted the dialectic of rights and obligations, autonomy and authority. Whether by accident or intention, the public discourse of the Church in this country is most audible on the topics of who can receive Communion, regardless of disposition, who has the right to celebrate the liturgy and in what way, and who has the right in conscience to take or refuse a vaccine.

The resulting discommunion is there for all to see, as is the lack of charity and love. As St. Paul reminds us, if we have not love, we have nothing.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity