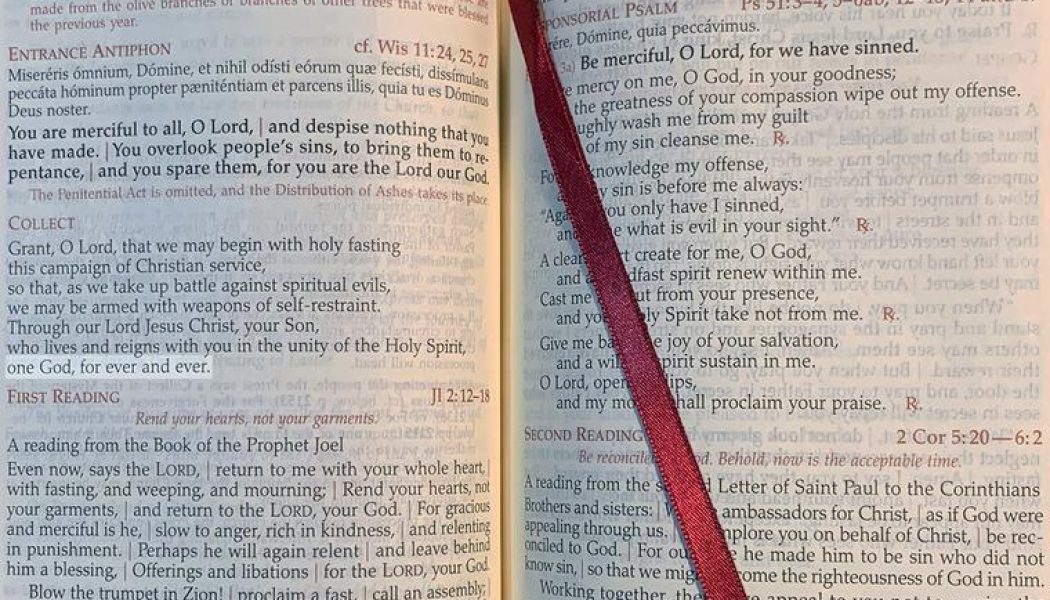

Last week, as reported by CNA, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) issued a note on the doctrinal concerns expressed by Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments in Rome regarding the use of the word “one” in the Collect of the Mass. “Specifically,” the USCCB stated in its note:

“the Congregation pointed out that the current translation — which concludes ‘[…]in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever’ — is incorrect.”

In other words, the faithful may be confused regarding the use of “one God” in this instance as a reference solely to Christ — rather than to his role within the Trinity. Is the Father one God, Christ another God and the Holy Spirit a third God? No: They are together three persons in one God.

As important as these doctrinal concerns are, however, Rome points to a related practical (and perhaps for most Catholics, a more accessible) reason for the change. Put simply, the use of “one” in the prayer, is not a correct translation from the original Latin text of the Roman Missal. In this light, the congregation’s correction points up an important facet of the liturgy — that how we say our prayers can be as important as what we say in them.

Minus One

“There is no mention of ‘one’ in the Latin, and ‘Deus’ in the Latin text refers to Christ,” the Feb. 7 USCCB note states — and any first-year Latin student can tell you exactly why this is the case.

According to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (54) — the official user’s guide to the Missal — there are three possible conclusions to the Collect of the Mass:

- If the prayer is directed to the Father: Per Dóminum nostrum Iesum Christum Fílium tuum, qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus Sancti, Deus, per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum (Through our Lord, Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, God, forever and ever);

- If it is directed to the Father, but the Son is mentioned at the end: Qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus Sancti, Deus, per omnia sǽcula sæculórum (Who lives and reigns with you and the Holy spirit, God, forever and ever);

- If it is directed to the Son: Qui vivis et regnas cum Deo Patre in unitáte Spíritus Sancti, Deus, per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum (You live and reign with God the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, forever and ever).

In each of these prayers, because Christ is the subject of the relative clause as denoted by the relative pronoun qui (“who lives and reigns …”), Deus agrees in case and number with the pronoun (both are singular nominative). In this typical lesson in textbook Latin, we may better see the congregation’s doctrinal concern, but, as a matter of language, it has other ramifications for the liturgy, as well.

Speak Truth With Power

As humans made in the image and likeness of God, we cannot escape the fact that with the divine gift of language has come a great responsibility: Language should mean what it says and say what it means. Nowhere is this more so than in the liturgy.

In 2008, when the new translation of the Mass in English was introduced, there were several changes to the way that English-speaking faithful were to pray the Mass. Take, for example, the translation of pro multis in the English translation of the Mass. Pro multis means “for many,” not “for all” (omnis). There were important doctrinal concerns involved in this change; but the revision also addressed the imprecise translation from the Latin.

Likewise, with the excision of “one” from the conclusions of the Collects, Rome and the English-speaking bishops have addressed not only a doctrinal issue but also a matter of imprecise translation.

According to Christopher Carstens, editor of the liturgical journal Adoremus and director of the Office of Sacred Worship for the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin, precision in translation is necessary if the faithful are to understand and embrace the liturgy in its fullness.

“Latin has been the primary language of the Latin Church through the centuries, and it captures the clearest expression of her faith,” he told the Register. “Imagine how we might rehearse in our minds — or out loud — an important question, or speech, or appeal to another. In a similar way, the Church has been developing and practicing her speech to God for millennia, and any translation ought to capture this same substance.”

Latin Root Words

In explaining why translation is so important to the liturgy, Carstens also underscores why Latin, the “mother tongue” of the Church, is so important as the foundation for all translations of the liturgy.

Pope St. John XXIII notes in his brief but incisive apostolic constitution Veterum Sapientia (“On the Promotion of the Study of Latin”) that Latin is “universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.” These qualities of the language readily carry over into the language of the liturgy as it is practiced in the West. (Greek, which is the original liturgical language for much of the Church in the East, possesses the same qualities.)

What better than an unchanging language, accessible to all and not restricted by general use or idiomatic nuances to a particular culture, to communicate a liturgy with the same substantive properties?

In Veterum Sapientia, published eight months before the start of the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII notes that, given these qualities, Latin “is important not so much on cultural or literary grounds, as for religious reasons.”

Latin, in other words, binds the truths of the faith in a way a local, ever-changing, vernacular language cannot. In fact, John XXIII warns bishops and other leaders of the Church to “be on their guard lest anyone under their jurisdiction, eager for revolutionary changes, writes against the use of Latin” in the teaching of the faith or in the liturgy itself.

John XXIII’s immediate successor Pope Paul VI also wrote about Latin, “a precious vehicle and instrument for the fusion of souls,” in connection with the liturgy.

In a 1968 address, which largely echoed Veterum Sapientia, Paul VI notes that Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, urges “the study and use of Latin.” He also states that Latin continues to have a formative value for the faithful — not despite — but because of the greater use of the vernacular in the liturgy. In providing greater access to the liturgy through the vernacular, Paul VI repeats his predecessor’s warning, emphatically addressing those “who believe that the Church should, from now on, abandon Latin — We repeat that it is evident that Latin must be kept in honor in the Church, for the lofty and grave reasons already mentioned.”

Rome’s instruction to excise “one” from the Collects in English honors Paul VI’s words and in so doing reaffirms the Church’s desire that Latin should maintain its place of honor in the liturgy by conforming all translations to the Latin as nearly as possible.

One Iota

On another note regarding language and the liturgy, it may seem to some that the Congregation’s directive is officious quibbling. After all, doesn’t the Church have anything better to do than worry the nuanced minutiae of the liturgy? But history bears out the importance of a word and sometimes even a single letter of the alphabet, as was the case during the deliberations at the Council of Nicaea — which resulted in, inter alia, the Nicaean Creed recited by the faithful at Mass to this day.

“In 325 at the Council of Nicaea, they were arguing not over a word but a letter — the iota [the Greek letter “i”],” Carstens noted. “That one little letter made all the difference between professing faith in Jesus who was God (homo-ousious, ‘one in substance’ with the Father) and Jesus who was not (homoi-ousious, ‘similar in substance’).”

Now as then, precision in language — Latin, Greek, English or otherwise — helps the Church to encounter Christ more perfectly in the liturgy.

“Truly, there are many problems facing the world and the Church,” Carstens said. “But praying correctly — professing accurately our belief about Christ and the Trinity — in no way distracts from these important tasks. Rather, as our relationship with God becomes stronger, we are better able to address the world.”

Speaking of …

Lex orandi, lex credendi. This Latin motto is traceable to the Church Fathers, but the idea behind it is the same in any language and any age, including modern English: “The law of how we pray [is] the law of how we believe.” Here’s another bit of Latin: the word for “prayer,” oratio, also means “speech.” Our prayers are directed to God, and speech is one of the primary vehicles by which we transmit these prayers.

Taken in this sense, it is also fair to say that the law of how we speak (that is, how we use language) is the law of how we believe — even if it comes down to the question of “one” word.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity