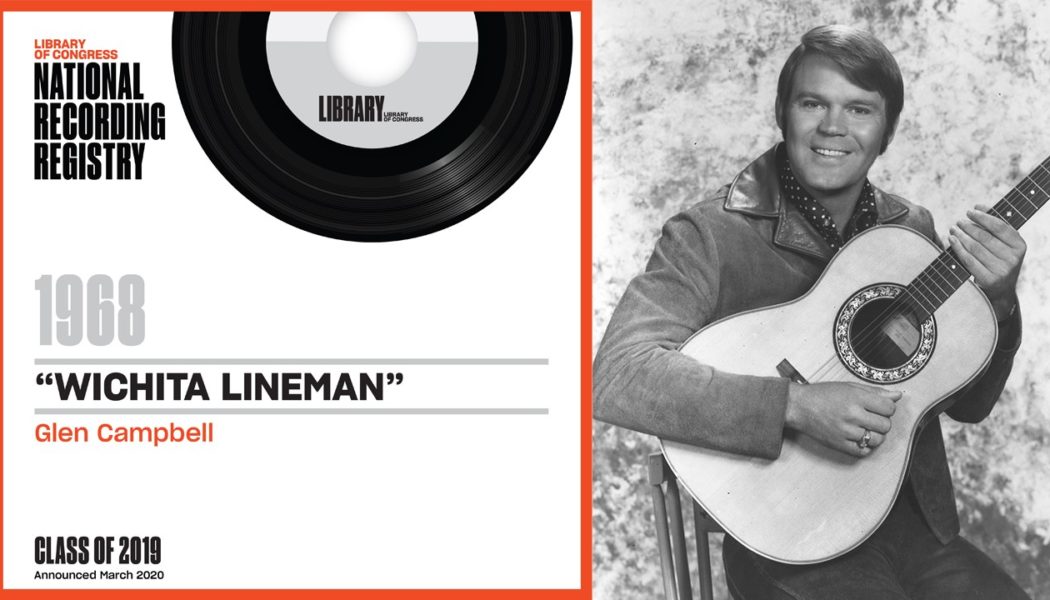

Glen Campbell’s 1968 recording of “Wichita Lineman by Jimmy Webb, was inducted into the National Recording Registry.

The Library’s National Recording Registry includes 1968’s “Wichita Lineman,” written by Jimmy Webb and first recorded by Glen Campbell. Kent Hartman, whose 2013 book “The Wrecking Crew” detailed the L.A. music scene that produced Campbell, wrote this essay for the Now See Hear! blog, drawing on his research. This version has been slightly adapted.

Glen Campbell had bigger hits during his illustrious career, but no song of his has stood the test of time or packed more of an emotional wallop than “Wichita Lineman.” It became Campbell’s oft-cited favorite out of the hundreds of songs he released during his Country Music Hall of Fame career. Yet only a serendipitous series of events allowed this platinum record to become what is now considered an American classic.

In the early spring of 1968, while sitting behind a funky green piano, high in the Hollywood Hills inside an old mansion that used to be the Philippine Embassy, the songwriter Jimmy Webb heard his telephone ring. As the author of the recent Grammy-winning single “Up, Up and Away” by the 5th Dimension, the red-hot Webb had been sequestering himself in an effort to write some new material.

The progress was slow — Webb was a perfectionist —and Campbell’s call came as a welcome distraction. Recent friends, the two had shared an almost immediate connection upon meeting. As both men later recalled in separate interviews with me, the call went something like this:

“Jimmy — hey, it’s Glen Campbell.”

“Glen, good to hear from you, man! What’s goin’ on?”

“Well, my producer, Al DeLory, and I are over here at Capitol cutting a new album and we’re short on material. We need something really strong. Do you think you could write us another ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’?”

Both an unexpected and heavy request, it gave Webb pause.

Campbell was referring to the crossover country smash that Webb had penned and given to him the prior year. It had provided Campbell with the first meaningful chart success of his career. Yet he wanted more; needed more. He was in his mid-thirties, and pop stars don’t have forever. Campbell knew that it took a Top 10 single to become headlining act, something he had dreamed of since his days playing the clubs in Albuquerque a decade before. And he was determined to make that leap.

Writing a hit song is hard enough, let alone one made-to-order. But Webb liked a challenge. And he knew that with Campbell’s career on the rise, there might be some good publishing money in the deal.

“Okay,” Webb said after some thought. “Let me see what I can do.”

He had a policy against copying a previous hit — even if it was his own — but he nonetheless thought that once again employing a geographical reference in the title might be a good start.

Sometime earlier, Webb had been driving through a flat and remote area of Oklahoma, his native state, absorbing the almost surreal nature of its isolation and seemingly endless horizons. He passed by a utility worker perched high on a telephone pole. The curious image of the anonymous, lone figure toiling in the heat in the middle of nowhere stuck in Webb’s mind. What might be the circumstances of this solitary man’s life? What were his thoughts?

Turning back to his piano after the phone call with Campbell, Webb spent the next couple of hours sketching out a song about the mysterious individual he had encountered on that lonely stretch of highway, then asked Campbell and DeLory to swing by the house that evening to take a listen.

“It’s not finished yet,” Webb warned as they sat down. “There’s no third verse.”

As Webb began playing and singing the basics of his new tune, Campbell flipped. He knew it was a hit. A story of desolation and longing, it spoke to the human condition, the universal need for love. The imagery about the singing in the wires and searching in the sun for overloads was out of this world.

“What’s it called?” Campbell asked.

“ ‘Wichita Lineman,’ ” Webb said.

***

Wondrous things can happen in a recording studio when inspiration becomes contagious.

Inside the subterranean confines of Capitol A, Campbell and DeLory walked musicians through the charts for the song. Something kept bothering the bassist, Carol Kaye. She and Campbell had played together as part of the Wrecking Crew, a group of secretly-used, top-notch Hollywood-based session musicians who played on dozens of Top 40 hits. They were good friends.

Looking over the chord sheets, Kaye saw that the tune lacked an identifiable opening lick. She had noticed the same deficit about the original version of Sonny and Cher’s “The Beat Goes On.” She had added a nine-note opening bass riff, then repeated it over and over, turning what at first had been a rather mundane rhythm track into a certifiable earworm.

Here, drawing on her jazz background, where less almost always meant more, Kaye quickly worked out a descending six-note intro for Campbell that she thought might do the trick.

Campbell thought it was perfect. But he also loved the tone of her bass. It was a Danelectro, a six-string, solid-body electric bass guitar made out of Masonite. It was often used in studios on pop recordings to add a higher sound than that of a standard Fender electric bass or an acoustic stand-up bass.

Campbell asked Kaye if he could borrow the guitar to play a solo to fill the space for the third verse that Webb had never finished. An unconventional but brilliant choice, the deep, resonant passage scored a direct hit, giving the song just the right quavering, tremolo-fueled melancholic interlude.

Webb chipped in with some inspiration of his own. Showing off his vintage Gulbransen church organ to Campbell one afternoon at his house, Webb mentioned that the keyboard’s unique bubbling sound evoked what he imagined to be the noise of signals passing through the telephone wires. As his lyrics said, “I hear you singing in the wire/I can hear you through the whine.”

Campbell was so taken with the idea that he had a company immediately come over and dismantle the monstrous organ and then reassemble it in the studio. Webb himself played just three notes on it, over and over, during the song’s fade. It proved to be the final piece to a masterfully executed production puzzle.

With Campbell’s plaintive vocals adding just the right touch of wistfulness and heartache, “Wichita Lineman” did indeed become the Top 10 hit he had so desperately sought. There would be no more anonymous guitar playing on everybody else’s records for this country boy. No more wondering whether he really had what it took to break out, to headline his own shows.

While “Wichita Lineman” rocketed to No. 3 on the national pop charts (and No. 1 on country charts), it became Campbell’s springboard to more success, including his own television show that ran for four seasons. As Campbell remarked to the British Broadcasting Corporation many years later, mentioning one of the song’s lines: “‘I want you for all time,’ I always say that to my wife, because it cheers her up.” There can be no greater poetic coda than that.

Kent Hartman is the bestselling author of “The Wrecking Crew,” along with “Goodnight, L.A.” and the forthcoming “A Cool Dark Place.” [Essay copyright: Kent Hartman]

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity