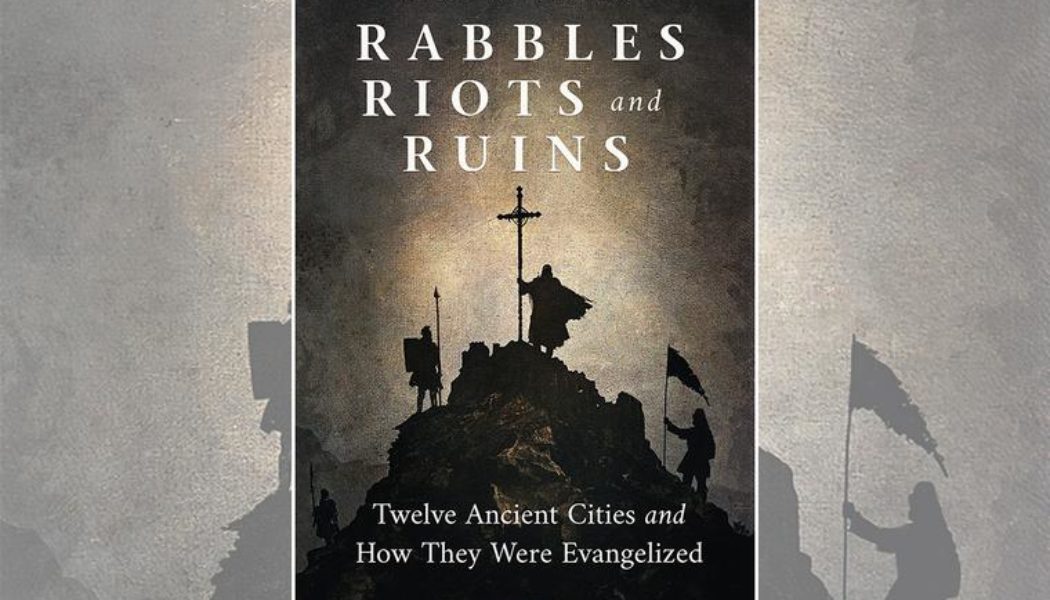

In times like these, it’s easy to despair about evangelization in the modern world. But a new Ignatius Press book by Mike Aquilina, Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins: Twelve Ancient Cities and How They Were Evangelized, not only offers some much-needed hope when thinking about evangelizing today’s culture but also serves as a guide on how to go about it.

The Register caught up with the book’s author at his home in Pittsburgh and asked if Christian hope can persist amid the despair of modern Western cities.

“Absolutely,” replies Aquilina. “Was there any earthly reason to hope in the midst of the Decian persecution? I can’t see any. The Romans mobilized as a police state for the eradication of Christianity. In the natural order, the world was falling apart, because of severe climate change and resulting famine and pestilence. This brought on political instability, with barbarians pressing in at every boundary. Very few emperors died in their beds; many were assassinated. And the Christians got blamed for everything! The volcanos erupted, apparently, and the clouds sent no rain because the gods were jealous and missing their allotment of sacrifice. Christians were dying, and yet Christianity was flourishing in a sense.”

Listening to him, perhaps the times we live in are not as depressing as one may think. Then he reminds us that during that time of intense persecution, St. Cyprian was inspiring his doctors in North Africa to bring about a new institution: the hospital, “with medical care extended to all, even the pagan persecutors.”

Aquilina makes the point that when times are bad, the Church tends to thrive while, interestingly, in good times we may become complacent.

It’s hard to disagree with any of that, in which case have we ended up right back where the Apostles started — namely, a world that is pagan?

“Some people say it’s worse, since our world is post-Christian,” continues Aquilina. “But I don’t know about that. I do think that God gives us what we need to get the job done in every time and place.”

In that case, is his latest work a historic study or a contemporary model for evangelization?

“Why not both?” he counters. “I think we have a lot to learn about our most ancient Christian ancestors. Through the first 250 years of Christian history, the Church grew at a steady rate of 40% per decade — and all that happened at a time when the practice of the faith was a capital crime.” A fact that is as consoling as it is impressive.

“We should be impressed,” observes Aquilina. “We should take notes!”

Now, while accepting there is no one model for evangelization with a single program, let alone a handbook, he feels he has glimpsed what may have been one of the key drivers in our Christian ancestors’ effectiveness as apostles.

“Evangelization happened in many ways, but the great constant was the importance of friendship,” he explains. “Christians were willing to share their faith with their next-door neighbors in spite of dungeon, fire and sword.” Citing as inspiration the anonymous Letter to Diognetus and the Octavius by Minucius Felix, both early examples of apologetics via dialogue with the then-dominant pagan culture, he suspects “that a disposition toward friendship will work as effectively today as it did in the second or third century.”

Living in any large Western metropolitan city, we seem to be adrift in a sea of hostile secular atheism, whether from civic society, academia or corporate bodies — so how can today’s Christians effect change in such a situation?

“Begin by loving the people who consider themselves your enemies,” Aquilina replies. “I often hear people say, ‘I’ll love them, but I don’t have to like them.’ Which is true, but it’s also a kind of copout.”

To this end, he points to G.K. Chesterton and his “astonishing capacity for friendship with the most unlikely people — people who disagreed with him on the most fundamental principles” as a good model for us to look to.

He also mentions the married couple Jacques and Raïssa Maritain who “made converts because they made friends.” They became “virtuosos at friendship,” he suggests. “I see the same dispositions in Perpetua and Felicity, who died in A.D. 203. They truly loved their persecutors, even in the midst of their martyrdom. We can do that. We can at least pray for the grace to be friends.”

But what else, besides the value of friendship, can we learn from how somewhere like Rome went from open hostility and mockery to a devout center of Christianity?

“We can learn hope,” says Aquilina. “In some of these ancient cities, Christians were torn apart by mobs gone mad. In others, they were tortured publicly by people who were geniuses of torture and who knew how to maximize pain over the longest duration possible. … Yet those very acts of depravity brought about conversions.”

He goes on to say that “in the mid-100s, a young man named Justin watched Christians go joyfully to their death. It made an impression on him, and he converted. A few years later, a North African convert, Tertullian, observed that ‘the blood of martyrs is seed.’ And it’s true.”

Then Aquilina says something even more startling about these onlookers of early Christian martyrdom: “Many of them felt a kind of jealousy and regret, because the martyrs had something worth dying for.”

Why this book now?

“I’ve actually been thinking about it for a long time,” he says. “Maybe 20 years ago I started planning a book on the four great patriarchal sees of the ancient Church — Rome, Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem. I couldn’t get a publisher interested in the project. I put it aside. But it never left me, and the cities multiplied over time.”

Now, with the book’s publication, who does he think is its audience?

“I want to give ordinary, non-academic readers an imaginative entry into the world of ancient Christianity. I want them to come to know these cities as something more than points on a map or items on a list.”

Therefore, in regard to a 21st-century London, it seems to be a case of an “ever ancient, ever new” formula when it comes to evangelization?

“I’d say it’s the disposition to genuinely love everyone,” he replies, suggesting the Apostles used the same modus and that that proved something transformative for their contemporaries just as it could be for ours.

“The same virtue is available to us, and it’s free for the asking,” he concludes. “I’m not saying it’s easy. I’m an extreme introvert, and I find it hard to make friends. But years ago, it became clear to me that there’s no more urgent task.”