Pope Francis exhorted the Congolese to forgive on his trip there this past week. How did the Congolese respond? The AP story reporting his homily told of some of the atrocities that the people of Congo suffered in a war between 1998 and 2004 that took the lives of some 5 million people, the largest death toll of any armed conflict since World War II, and have suffered in the years since, even more intensely in recent years. I have not read any reports of reactions to the Pope Francis’s exhortation.

Forgiveness is absent from the panoply of practices plied by the “international community” – that vast collection of NGOs, diplomats, relief workers, peacekeepers, human rights activists, and international lawyers – in their efforts to bring peace to countries riven by war and genocide. They conduct trials, truth commissions, reparations, relief, economic development efforts, trauma healing, medical relief, and efforts to combat corruption, but they do not advocate forgiveness. When they speak of forgiveness, they warn that it disempowers, burdens, denies justice to, and imposes religion on victims. They might think that the Congolese would chase Pope Francis out of the country.

Forgiveness takes on a different meaning in Christianity. Jesus commanded his hearers on a hillside to “forgive our debtors” because God has forgiven their debts. Forgiveness is not just a wisdom teaching, then, but is done in response to God. And through God. No longer does a victim of atrocity stand alone before and dwarfed by the evil of a perpetrator. Now there is a third party involved, Jesus Christ, who is infinitely greater than the evil and who incorporates all victims in overcoming it through his own forgiveness on the Cross. Reports the AP story:

“He showed them his wounds because forgiveness is born from wounds,” Francis said. “It is born when our wounds do not leave scars of hatred, but become the means by which we make room for others and accept their weaknesses. Our weakness becomes an opportunity, and forgiveness becomes the path to peace.” Through forgiving, victims become peacebuilders.

Almost ten years ago, in cooperation with the Refugee Law Project, I conducted a study of forgiveness among 640 Ugandans who had lived through armed conflict. I found that 86% of respondents favored forgiveness in the aftermath of armed violence and 68% of victims reported having practiced forgiveness. They cited their Christian faith as the primary reason for forgiveness (or the Muslim faith in 20% of cases).

I suspect that the estimated 1 million people attending Pope Francis’s mass understood forgiveness. It is one practice in what has become known as Catholic peacebuilding. The Church used to offer mainly the just war ethic in thinking about war and peace. In Ukraine, this ethic still has great relevance. After the Cold War, though, in a wave of societies around the world, peace has meant not the decision whether to go to war but rather the task of building stability and justice in the aftermath of colossal civil war, genocide, and dictatorship. Peacebuilding has emerged. The Catholic practice of it, though, is distinctive from that of the international community (while also sharing a lot in common with it). Its favor of forgiveness is the sharpest of these differences.

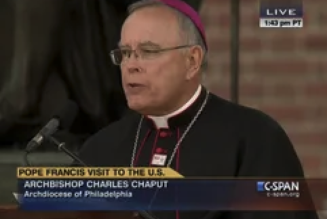

This past August, the Journal of Social Encounters published an issue on “Peace Bishops: Case Studies of Christian Bishops as Peacebuilders.” The editor is Ron Pagnucco of the College of Saint Benedict, St. John’s University. The journal is published in collaboration between this institution and the Center for Social Justice and Ethics at The Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Nairobi, Kenya. The special issue is innovative, full of well-crafted case studies, and a fine introduction to Catholic peacebuilding. The Bishop of Rome, following the example of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, has shown this past week that he is the most famous peace bishop.