I wish someone had warned me that the denouement of #TheMiracleClub movie I saw a few nights ago would be a scene set in a hotel named for St. Bernadette in Lourdes where Irish women from different generations share with one another—with great fellow feeling—about how they’ve tried to abort their children and that somehow resolves decades of rancor.

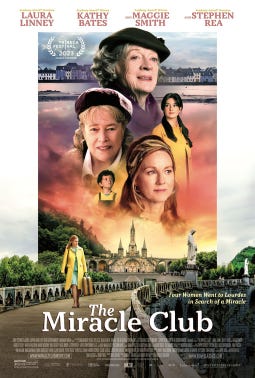

The superficially charming portrayal of 1960s Irish Catholics dressed up in the bright fashionable colors of the era (even the doors of the Dublin row houses where they live are painted with the same bright colors—in contrast with the shabbiness inside) with some stellar actors, including Maggie Smith, Kathy Bates, and Laura Linney, is rotten at its core.

A lot could have been shown in this movie about the cruelty of the double standard that was in effect during those years, which are the same years when I was a young woman and witnessed the double standard for myself firsthand.

When a woman got pregnant outside of what we used to call wedlock, she usually was sent away to avoid shaming the family and ruining her reputation. She would go to a home for unwed mothers until the baby was born, where she would give the child up for adoption. She had little choice, unless her parents were willing to let her have the child and raise it in their home, when that would mean they were able to face society’s scorn for themselves and for the bastard child.

It was indeed deplorable that shame was heaped on any woman who took the great risk of having sex and possibly getting pregnant with a man who quite probably wouldn’t want to marry her or raise a child with her, and grossly unfair that men were excused for sowing their wild oats before marriage. The woman who was known to have lost her virginity was thought of as ruined. She was told that no decent man would want to marry her. Horny boys looking for a good time would from then on see her as easy game.

The hypocrisy that encouraged young men to be cads and that persecuted women who were told they were foolish for “putting out” before marriage was rampant. Society’s later acceptance of birth control and of women being promiscuous is mistakenly supposed to have leveled the playing field, and the availability of welfare for single women with children and more employment options for all women, plus easy access to and acceptance of abortion seems to have made things more fair.

The myth of sex without consequences was born and it seemed within reach of all. But the truth is that the devastating consequences of that myth are all around us.

Instead of encouraging men to exercise self-control and to treat women as people instead of objects, the change in mores actually encouraged women to think they could achieve true freedom only if they were able to act as badly as the worst of men, and allowed men to treat women and any children they fathered as disposable without a qualm.

But even though the devastating effects of the double standard would be more appropriate as the background for a movie set during that time, that is not what this movie about one woman’s unwanted pregnancy is about. Instead, this movie set almost 60 years ago overlays modern morality (or immorality) on the characters.

At the start of the movie, when middle-aged Laura Linney’s character Chrissie shows up in the working-class Dublin neighborhood of her childhood returned from Boston for her mother’s funeral, dressed and groomed expensively, she is greeted with animosity by Lily, the character played by Maggie Smith, and by Eileen, played by Kathy Bates. Chrissie had been banned from her home decades earlier by her mother Maureen, who had been a close friend with Lily, and she has returned for her mother’s funeral. How Chrissie lived the ensuing years as a single woman is not explained.

I wish someone had warned me that the resolution at the core of #TheMiracleClub movie I saw last night would be a scene set in a hotel named for St. Bernadette in Lourdes where women from different generations share with one another with great fellow feeling about how many of them tried to abort their children and that somehow resolves all the decades of rancor between them.

The youngest woman, Dolly, is told by her friends that she doesn’t need to confess to a priest, but she needs to tell them to get whatever it is off her chest, so she confesses to them. She cries because her darling curly-haired red-headed little boy doesn’t talk. She hoped for a miracle in Lourdes for him to stop being mute. But it didn’t happen.

She tells her friends that she thinks she ruined him because she tried to abort him. (Let’s leave aside the reality that she tried to kill her, fortunately, still-living much-loved little boy, which if she succeeded, she surely would have ruined him.)

Dolly feels guilty (as she should, and she needs a real sacramental confession), but that’s irrelevant in this cinematic world where the director casts modern Ireland’s pro-abortion attitudes backward in time. In this scene, Dolly gets excused for her guilt and reassured she didn’t do anything wrong by trying to abort her child, instead of being encouraged to seek sacramental forgiveness.

How did she do it? Dolly tells the others she filled up a bathtub and then got five bottles of whiskey. “Oh dear,” I think it was Eileen who says sympathetically, “You could have killed yourself [poor dear you might have injured yourself trying to kill your child], drinking five bottles of whiskey.” “I didn’t drink it. I put it in the tub. You’re supposed to sit in it.”

Eileen (who is the happy mother and grandmother of many children) then rather inexplicably says, “You didn’t do anything wrong. We’ve all done that. I’ve thrown myself down the stairs more times than I can count.” Is she actually saying that all respectable married women tried to abort their children in those repressive old times, and there’s nothing the matter with that? Yes, I think she is.

“Oh that’s an old wives tale,” says another. “You can’t abort a baby by sitting in a tub full of whiskey.”

Chrissie chimes in with this nonsense, “No the water has to be boiling.” She repeats this nonsense twice.

And we soon learn that she aborted her own baby. Whoever wrote the movie script mistakenly believes that in the mid-1960s, there were abortion pills a woman could take, and that’s what Chrissie did, having been given the address of an abortionist by her landlady once she found a room to rent overseas in Boston.

The Maggie Smith character Lily was the mother of Declan, the father of Chrissie’s baby. Chrissie tells her that Declan and she were happy together and that her son wanted to marry her and raise the child with her, except for Lily’s intervention. Lily is cruel to the newly returned Chrissie according to the plot because she feels guilty because she convinced her son that Chrissie was trying to trap him. (A common accusation in that time when a woman got pregnant when the guy was just using her was that she conceived deliberately so as to trap him into marrying her.) And rather clumsily another scene implies Declan was so distraught by feeling betrayed by Chrissie that he drowned himself.

Implausibly, after Chrissie reveals she aborted the only grandchild of Lily, all animosity between the two disappears. What grandmother would react that way without seemingly giving any thought to learning the fact that her only grandchild had been aborted?

Also, the movie implies that even the priest who accompanies the pilgrims to Lourdes doesn’t really believe in the mumbo jumbo. He says that it doesn’t matter whether the miracles reported at Lourdes were true. Chrissie, the character who seems to personify modern women, certainly doesn’t believe they are.

Kathy Bates’ character, Eileen, who was supposed to have been close friends with the Laura Linney character Chrissie, and Declan, the boy who fathered Chrissie’s aborted child, when they were young, is not believable as being the same age as Chrissie, since the two actresses are quite far apart in age, and her character’s animosity towards her former friend is inexplicable, although it is hinted that perhaps it is because she loved Declan and resented being the one not chosen.

So many plot holes. So much bad writing, I wish I could unsee it.

![My Gay Father-in-Law [Must-Read]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/my-gay-father-in-law-must-read-327x219.jpg)