The most heavily anticipated economics book of the year makes a radical argument: Having married parents is good for kids.

I know, I know. It seems like a joke, right? Of course having two involved parents living in a stable home together is good for kids. Anyone who has considered having children with a partner or was ever a child themselves must know that. But for years, academics studying poverty, mobility, and family structures have avoided that self-evident truth, the economist Melissa Kearney writes in The Two-Parent Privilege, released this week. And while the wonks avoided the topic, the rise of single-parent households in America exacerbated inequality and contributed to astonishingly high rates of child poverty.

“The high incidence of single motherhood has spread to what we might think of as the middle class,” Kearney told me. “It has undermined the economic security of a much wider swath of the population.”

Kearney, an economist at the University of Maryland, has amassed reams of evidence on the rise of single parenthood and the way it has put lower-income children at an even greater disadvantage to their high-income peers over the past four decades. Her book shows that marriage itself matters; it is not just a correlate of other factors, such as wealth and education.

So far, many readers on the left have concurred that this is a problem they should have been paying more attention to, while those on the right have had a simpler response: Duh. “Happy to welcome Melissa Kearney to the club of folks who understand more kids would be better off if we had more two-parent married families,” quipped the American Enterprise Institute’s Naomi Schaefer Riley, one of many scholars from the prominent conservative think tank who have lauded the book.

But it is worth asking: What good comes of pointing out that many people could use a cohabiting partner and that many kids could use a second involved parent? Kearney has written an important, careful book on a topic that is an “elephant in the room,” as she puts it. Still, I am not sure anyone has any idea what to do with that elephant.

Kearney’s three teenagers benefit from living in a two-parent home, she told me; she herself benefited from growing up in one. Kearney’s father worked odd jobs and ran a printing business; her mother was a secretary and schoolteacher. There wasn’t a ton of money to go around. But Kearney became an intergenerational success story, going to Princeton before getting her Ph.D. at MIT and gaining prominence as an academic. “Wanting to know the answer is different than knowing the answer; she wants to know the answer,” Phillip Levine, an economist at Wellesley College and a frequent co-author of Kearney’s, told me. “The greatest compliment you can give to an academic, I think, is to credit their intellectual curiosity.”

Much of Kearney’s work is about family planning and family structures. Did the rollout of the MTV show 16 and Pregnant reduce or increase teen pregnancies? (It reduced them.) Why is the American birth rate falling? (There isn’t a simple answer, but women’s “shifting priorities” seem to have something to do with it.) If men suddenly earn more, do they become more likely to marry their partner? (No.) Do increasing housing costs change fertility rates? (Yes.)

Kearney’s own research and the research of other scholars convinced her that the rise of single parenthood was an important and overlooked social phenomenon—a key to understanding the country’s low rates of mobility and high rates of poverty. Since the 1980s, marriage rates have fallen for everyone, particularly for folks without a college degree. Over the past 40 years, among kids whose mother had a bachelor’s degree, the share living in a two-parent home dropped from 90 percent to 84 percent. Among kids whose mom did not have a high-school diploma, the share went from 80 percent to 57 percent.

A single-parent home is typically a lower-income home. One parent means one income. Two parents means two incomes, or at least the potential of two incomes. And most single parents are nowhere near the top of the earnings distribution. According to census data, single mothers make an average of $32,586 a year; roughly 29 percent of single parents fall below the country’s very low poverty line. Married couples take home an average of $101,560. If you’re trying to understand why such a wealthy country has such high rates of child poverty, single parenthood is a big cause.

Kearney told me that she often heard from her peers—“economists who are inclined to downplay the importance of marriage”—that what she was describing was really an income issue, not a marriage issue. Kids with two parents earning a cumulative $55,000 a year have not-dissimilar outcomes to kids with one parent earning $55,000 a year, after all. But the kid with one parent would economically benefit from having a second parent in the household, Kearney told me, sighing in frustration. And nobody is suggesting that the government grant single parents tens of thousands of dollars a year to make up for the lack of a second earner in the home.

Household finances are not the only issue. Single parents have fewer hours to read, talk, and play with their kids than co-parents do. And they tend to be stretched thinner. This is not to stigmatize single parents or argue that they are not doing a stellar job with their kids, Kearney was at pains to tell me. Many kids raised by single parents succeed (two of the past three Democratic presidents among them). It is just to say that parenting is hard. Doing it alone is harder. And that difficulty shows up in the aggregate statistics.

Particularly for boys. “Girls internalize their struggles more,” Kearney told me. “I don’t know if it is that girls aren’t struggling as much. But boys are certainly struggling in ways that manifest themselves such that it impedes their educational performance, progress, and ultimately their economic life outcomes.” All in all, kids growing up with only one involved parent are less likely to obtain a college degree than their peers. They earn less. They are more likely to fall below the poverty line. And they are less likely to get married and more likely to become single parents themselves.

Why has marriage declined so much? Hard-to-quantify cultural factors are surely at work, but so are easy-to-quantify economic factors. Earnings for men without a college degree have not just stagnated, but fallen in real terms. At the same time, women have become more likely than men to go to college or graduate school, and their incomes have risen regardless of educational attainment. The economist Na’ama Shenhav has shown that a 10 percent increase in women’s wages relative to men’s wages produces a three-percentage-point increase in the share of never-married women and a two-percentage-point increase in the share of divorced women.

Women are going it alone—not because they want to, but because they feel that they have no choice. In straight couplings, women tend to like to date men who earn more than them and men tend to like to date women who earn less; thus, women’s thriving and men’s flailing have left a “marriageability gap.” In surveys, women overwhelmingly say that they want to get married. (That includes young people: In one poll released this week by the Knot Worldwide, just 8 percent of Gen Zers described marriage as “outdated.”) But they report struggling to find someone with a steady job, someone to match their sensibility and ambition. So they have kids on their own.

Those kids, on aggregate, are worse off than many of their peers: That’s Kearney’s elephant. It’s a big one and an awkward one. How a family works “is really no one else’s business,” she writes. “I am not blaming single mothers. I am not diminishing the pernicious effects of racial bias in the United States. I am not saying everyone should get married. I am not dismissing nonresident fathers as absent from their children’s lives or uninterested in being good dads. I am not promoting a norm of a stay-at-home wife and a breadwinner husband.”

What to do, then? Conservative scholars, of course, have a boatload of policy and social prescriptions. Parents should get married, they argue. Nonresident fathers should step up. Families with a breadwinner dad and stay-at-home mom tend to be good for kids. Couples should try to work it out instead of divorcing. Traditional values often result in happy children.

“One of the reasons there’s a class divide in America today is that more educated young adults are more likely to move slowly into their relationships, and make better decisions about friendship and mating,” Brad Wilcox, the director of the National Marriage Project and the author of the forthcoming book Get Married, told me. “If our leading institutions clearly articulated the standard that marriage matters, it would be helpful in rearranging how people approach entering into marriage and entering parenthood.”

Liberals seem more stuck. The idea of the government pressing for marriage feels icky. Plus, marriage rates are heavily stratified not just by income and educational attainment but by race; Democrats, like Republicans, have a long history of supporting and implementing brutal, paternalistic policies that break Black families in the name of “fixing” them. And many policies aimed at raising marriage rates or encouraging co-parenting just don’t work. George W. Bush’s “marriage cure”—federally financed classes and outreach programs promoting wedlock—was ineffective. Responsible-fatherhood programs? A randomized controlled trial showed that they do not lead to more in-person contact between dads and kids or increased financial support from fathers to their children.

Kearney supports figuring out better interventions for parents and couples, and implementing them. “How many high-income couples pay for high-priced couple’s therapy to keep their relationship alive?” she said to me. “There’s a skittishness around the idea that the government would provide funding to programs that provide relationship education to low-income couples.”

She advocates for improving men’s economic situation. She champions strong anti-poverty policies to support low-income kids and low-income families, including the expanded child tax credit. Yet “no government check—even one much larger than what’s politically feasible in the U.S. today—is going to make up for the absence of a supportive, loving, employed second parent,” she has argued. To that end, Kearney also proposes working “to restore and foster a norm of two-parent homes with children.”

Yet that norm already exists, something Kearney acknowledged when we talked. Few single mothers want to be single mothers, especially not the low-income ones. They just can’t find anyone to stay with them, or anyone worth staying with. Polls do show some erosion in the idea that marriage is important for couples with kids. But this seems as much an effect of the rise of single parenthood as a cause of it.

The real elephant in the room, I think, is that the United States doesn’t want to contemplate, let alone create, a policy infrastructure that supports single parenthood. It doesn’t want to make sure that kids thrive with a single earner in the home. It won’t do this even though it seems obvious that a large share of children are going to grow up with one parent going forward, and even though we aren’t realistically going to increase the marriage rate among lower-income Americans. We don’t want to build a society where children are seen as a collective gift and a collective responsibility. It’s not single parenthood that’s failing these kids. We all are.

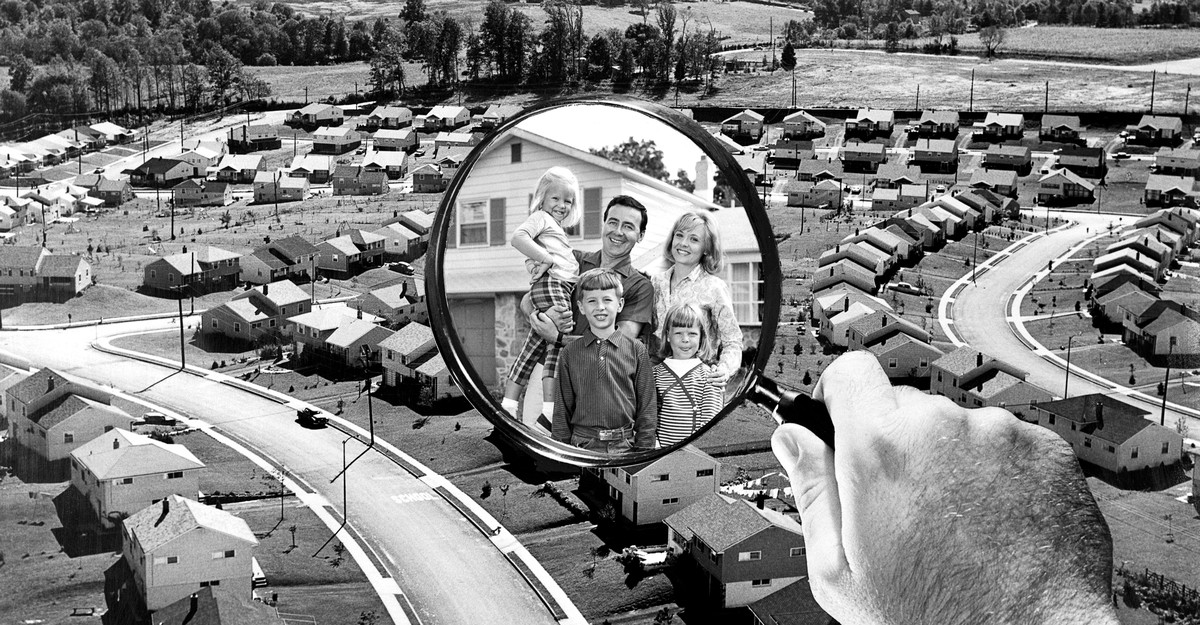

![Is single parenthood the problem? If so, should the government try to fix it? [Note: The Atlantic paywall]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/is-single-parenthood-the-problem-if-so-should-the-government-try-to-fix-it-note-the-atlantic-paywall-1050x600.jpg)