This Sunday we hear the passion and death of Jesus Christ, but only after Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The Church gives two options for the palm procession before Mass for Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion (Year B): Mark or John’s account of the entrance of Jesus into Jerusalem.

Jesus was not the first king to enter Jerusalem. But the other kings’ entrances were totally unlike his.

The great conqueror Alexander the Great entered Jerusalem in 329 B.C. as a giant man wearing a plumed helmet atop an enormous white warhorse. Seeing him, the city leaders quaked with fear. He demanded taxes, and got them, but he spared the city — perhaps because his teacher, Aristotle, taught him to admire monotheism.

Roman general Pompey the Great entered Jerusalem in 63 B.C., perhaps in the war chariot he is often depicted in. He massacred thousands of Jews who attempted to defend the Temple, then captured the city and entered the Holy of Holies, desecrating it.

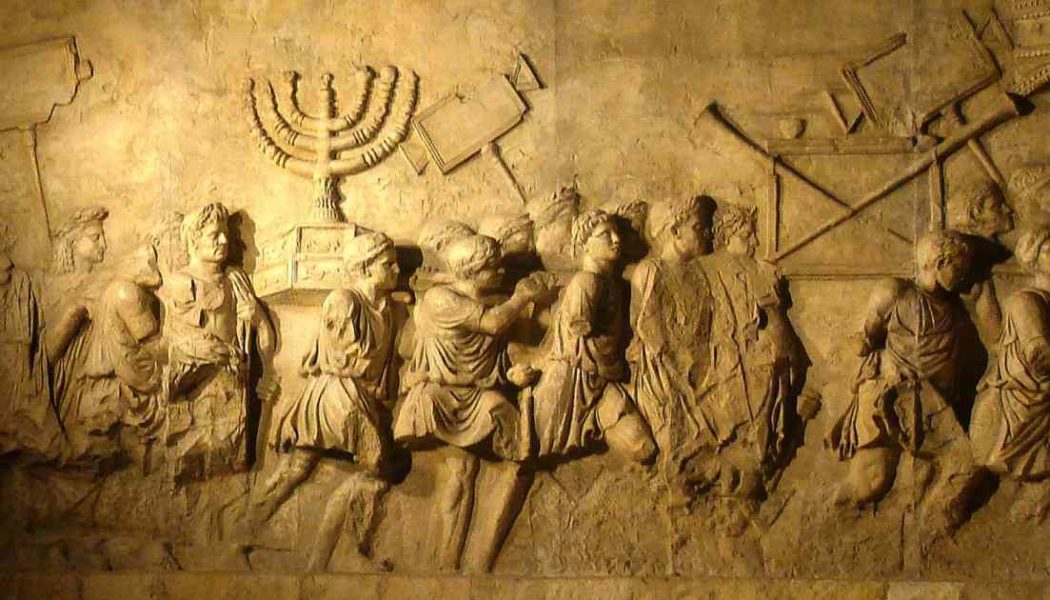

Finally Titus came in 69 A.D. and entered Jerusalem with catapults, battering rams and siege towers. He destroyed the Temple amid a cataclysmic fire, but not before stealing the treasures of the Temple, as depicted in the Arch of Titus in Rome (pictured above).

They came to the Jerusalem dressed for battle and had their way with it. Jesus entered around the year 33 A.D., unarmed, riding on a donkey, and Jerusalem had its way with him.

Yet it was Jesus, the man of peace, not the great men of war, who had the lasting victory.

We tend to think of Jesus’s donkey as a sign of humility, because it is an inferior beast — but it is actually a sign that he is an even greater king.

John’s Gospel cites the prophet Zechariah’s description of the Messiah king’s entry into Jerusalem. Zechariah says: “Shout for joy, O daughter Jerusalem! Behold: your king is coming to you, a just savior is he, humble, and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

This is actually a more powerful image than those military conquerors. Zechariah goes on to say: “He shall banish the chariot from Ephraim and the horse from Jerusalem. The warrior’s bow will be banished, and he will proclaim peace to the nations.”

This is a more powerful entrance than any of the others because it is a power that doesn’t need to push itself brashly forward.

“Some boast of chariots, and some of horses; but we boast of the name of the Lord our God,” says Psalm 20.

The prophecy of Zechariah proclaims that the donkey-rider will have a kingdom greater than Alexander’s or Caesar’s: “His dominion will be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth.” He even says how this will come about — “by the blood of your covenant.”

The quiet, constant, subtle but unstoppable power of Jesus is shown in the inordinate amount of time the Gospel of Mark spends describing how Jesus got his donkey to begin with. Jesus seems to know how and where his disciples will find a donkey and seems to be able to claim the animal with a word. You get the sense that Jesus is the master of this creature and all creatures, this circumstance and all circumstances; this moment and all time.

Jesus enters as the ultimate power: The quiet power of divine majesty.

In his Gospel’s telling of the tale, Luke paints this moment as the fulfillment of the angels’ Christmas prophecy. “Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will,” the angels declared. At the entry into Jerusalem, the people proclaim “Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!”

And at first, this all seemed to go better for Jesus than for the Roman conquerors, too. Jesus didn’t have to fight for the city. “Many people spread their cloaks on the road,” says Mark. This is a sign of homage due to royalty. They cry out, saying, “Hosanna,” which means “Save us!” or “Hail, Savior!” They announce the “kingdom of our father David,” and say “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord,” from Psalm 118.

You have the sense that the victory promised by that Psalm has arrived — the defeat of worldly power by the calm, conquering God.

Matthew reports that “the whole city was shaken and asked, ‘Who is this?’” The crowds reply, “This is Jesus the prophet, from Nazareth in Galilee.” Not “a” prophet — “the” prophet.

But then we get the day’s main Gospel reading, and see this all-powerful one die a humiliating death.

Nonetheless, Jesus goes to his death with great presence and dignity.

He is deliberate. He knows that a lot of attention will be paid to the way he dies, so he is careful with what he does and with what he says. Every movement and every word matters.

The night before he dies, he institutes the Eucharist — that “blood of the covenant” that Zechariah told us will conquer the world. At the Last Supper with his apostles, Jesus makes the Eucharist something that will endure in his kingdom.

He is forthright as he prepares his followers. Jesus doesn’t mince words. He warns them that he will be betrayed. He tells them they will be scattered. And he doesn’t let his “captain,” Peter, be less than forthright. Now is not the time for bravado or wishful thinking: It is the time to face the truth — and the truth is that Peter will fail.

In the Agony in the Garden, Jesus shows his state of mind. He is courageous enough to die, but honest enough to request that, if it’s possible, he could be spared.

Then when he is betrayed and put on trial, he stands up to his accusers with dignity. He doesn’t beg for mercy or loudly protest his innocence. He refuses to answer dishonest questions and, ultimately, shares the truth about himself.

Finally, he goes to his final end with royal dignity, by his own power.

The people misunderstand and insult him. He ignores them. He is the figure described in the Frist Reading from Isaiah.

“I gave my back to those who beat me, my cheeks to those who plucked my beard; my face I did not shield from buffets and spitting,” he says. “I am not disgraced. I have set my face like flint, knowing that I shall not be put to shame.”

He is confident about who he is. The bad attitudes of the weak don’t affect him.

But he is more than just a great king, of course. In Sunday’s Second Reading, St. Paul says “God greatly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

The great conquerors of the past came to bring peace by pacifying opponents, by violence. Jesus came to bring peace by transforming opponents, by loving them; a love that even submits to violence.

He came to go down to the depths below us and lift us up. And his power reigns from the donkey to the cross to everyone who suffers with him to this day.

Images: Wikimedia