Wednesdays are always my busiest days, when it comes to life at my computer keyboard.

First of all, there is my “On Religion” column deadline. That’s been carved into my calendar for almost 36 years. This is also the day when I work with the Lutheran Public Radio team to research and produce the weekly “Crossroads” podcast. We’ve been doing that for over a decade.

Right now, you can toss in lots of packing for our move from Oak Ridge up to the Tri-Cities region in the mountains of Northeast Tennessee. Late last week, I reached for a book (during an online interview with Jonathan “The Anxious Generation” Haidt) and realized that I had already packed that shelf and the boxes were sitting in my future office nearly 150 miles away. Then, dang it, the same thing happened with a different book during some email chatter with a Nashville media pro a day later.

Yes, things are extra busy in my neck of the woods. Thus, please allow me to offer a rather quick Rational Sheep post today, a natural follow-up to my recent post that ran with this double-decker headline:

Should men of the cloth hang out …

In bars? Taverns? Walmarts? Ordinary people places like Waffle House?

The big idea was that interesting things often happen when people with religious vocations hang out, well, in perfectly ordinary corners of the public square.

Things get really interesting when clergy wear distinctive garb that signals their presence to people in Big Box stores, at fast-food tables, in the quiet aisles of bookstores and even on nearby barstools.

Some strangers can get nasty (please see the classic anecdote in that first column). But on the positive side of things, I noted that:

…. My Orthodox godfather — founder of St. Anne Orthodox Church in Oak Ridge — tells stories about what happens when he wears his traditional cassock while going hither and thither in the hills of East Tennessee. Things get especially interesting at Walmart and Waffle House.

People ask Father Stephen Freeman all kinds of strange and complicated questions and it doesn’t matter if the shoppers are hard-shell Baptists, Methodists or generic evangelical Protestants.

It’s the cassock. But he can handle it, with since he has both a thick Southern accent and Duke University graduate-school smarts in systematic theology. He once told me: “I’m the priest of Oak Ridge, whether people are Orthodox or not.”

Father Stephen’s bottom line: A priest isn’t just someone who serves inside the walls of his Church. He is a priest for everyone.

When I wrote that post, I wanted to include material from an “On Religion” column that I wrote 25 years ago about a nun’s decision, after years of life in “secular” clothes, to return to the attire she wore early in her ministry.

I wanted to quote that column, but I couldn’t since — for the life of me — I could not find the right combination of terms that would pinpoint it in my Tmatt.net archive.

Google simply could not, or would not, find that column. I don’t know why since, strangely enough, one of my many search attempts contained a trio of words that should have allowed the gods of Google to find it. #Hmmmmm

Meanwhile, the packing process provided an old-school answer to that very problem. Take that, Google.

Last week, I was working my way through a heavy box of old magazines and journals — the kind of analog stash that journalists who spent decades in the pre-Internet age tend to have lined up on shelves in the basement. Lo and behold, I found the issue of the New Oxford Review that, long ago, alerted me to this particular nun’s essay.

Behold! Here is that 1999 column: “Sister Winifred’s veil: This is not a news story.” Knowing this sister’s unique name made the search engine work, finally.

Please consider this flashback an update on the previous post!

Whenever Pope John Paul II travels, the events that receive the most attention are his spectacular public Masses and encounters with heads of state and other dignitaries.

But these tours also include quieter rites and meetings with priests, nuns and lay people. The pope leads prayers, delivers words of advice or encouragement, offers his blessing and shares a few moments of fellowship.

In other words, these events are rarely “newsworthy.” This depends, however, on one’s point of view.

Sister Winifred Mary Lyons was one of 130,000 New Yorkers at a 1995 papal Mass in Central Park and, later, she was in St. Patrick’s Cathedral when John Paul led the recitation of the rosary. Afterwards, she had a brief chance to meet the pope. Years later, she still has trouble describing what she believes was a holy moment.

“As I walked out of the cathedral, I met a friend to whom I immediately said that I was going to return to wearing a veil,” said Sister Winifred, a pro-life leader in the Archdiocese of New York’s schools. “I could not believe I was saying it. The words were not mine.”

It would be hard to make a more symbolic decision. It had been 23 years since Sister Winifred set aside her veil and started wearing “secular clothes” while going about her work in the Sisters of Charity. During the 1960s and ’70s, she was one of thousands of women and men in religious life who rode the waves of change that rolled through Catholicism and the culture. She dyed her hair and pierced her ears. Her peers changed and so did she.

The first time she tried on her veil, again, she looked in a mirror and saw an image of herself as she was years earlier. This startled her, she said, and she literally lost her breath. In an essay in the New Oxford Review, she explained how this simple veil has brought her a renewed sense of her ties to the past, while her daily work continues to carry her into the present.

Sister Winifred thought she might encounter some resistance to her decision. But in all honesty, she said, this has not been the case, even though she knows that many people – in holy orders and in the pews – consider this a “monumental decision” after a tumultuous era.

The reactions of people around her have been quite touching, she said.

“Being greeted on the street was something I had totally forgotten. Moreover, the witness value has overwhelmed me: I know I cause others to think about God, if only for a few seconds, and I realize afresh the public dimension of the consecrated life and the hunger there is for it in this world. Again, this is something I had forgotten. I am in no way negating the witnessing I did and which all women Religious do, daily, but we do it after we identify ourselves. Wearing the veil, we do it in spite of ourselves.”

It’s fairly easy, she said, to describe the outward manifestations of this “public dimension” to her decision. She can see it in people’s eyes and hear it in their voices. Once again, total strangers walk up and ask her to pray for them. It’s easy to detect an increased vulnerability and openness in the people she sees in her work – especially among the women she counsels and consoles in crisis pregnancy centers.

Yet her decision wasn’t about taking some kind of a public stand, she said. The biggest changes that have taken place since her return to wearing a veil haven’t been on the outside. This really isn’t a news story, she said. It’s just part of her story.

“It’s very difficult to put this into words. The change on the outside is important. I know that,” said Sister Winifred. “But what happened to me on the inside has been so much deeper – deeper than all of the external changes. It is this inner reality that is so much more important. … Yet that’s the part of this that is beyond words. It’s a mystery to me, too.”

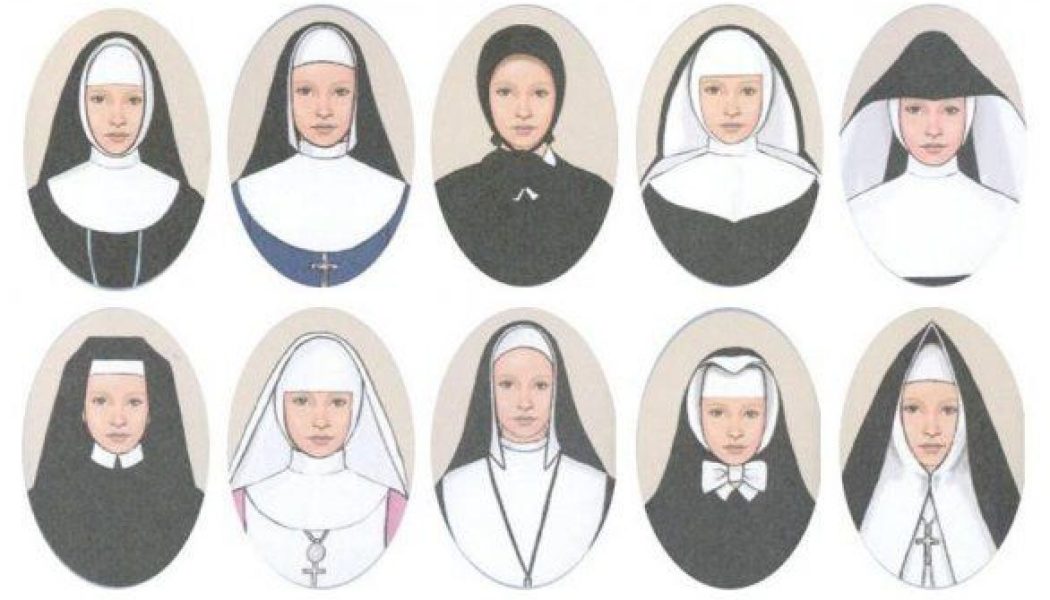

FIRST IMAGE: A collection of images of traditional habits for Roman Catholic nuns, found at Pinterest.