As was her custom in the spring of 1970, Joy Piccolo spent a little time one morning with folded hands at St. Catherine of Siena, the Catholic Church across the street from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Afterward, she made her way to see her husband Brian at the hospital, and crossed paths with his doctor on the sidewalk. They exchanged pleasantries, and then Dr. Edward Beattie got to the point.

Advertisement

“It’s not looking good, Joy,” he said. “We’ll keep him as comfortable as we can. It’s not going to be long.”

The words were not unexpected. But they were stunning.

Now 76, Joy Piccolo-O’Connell still gets emotional talking about the feeling she had that day.

“It was very hard for him,” she says, pausing, then taking a deep breath. “It was hard because he loved those kids.”

Six months before the conversation that Joy cannot forget, Brian was the kind of father who would play all day with his three adorable daughters. He delighted in taking Lori, Traci and Kristi shopping for shoes and wading in the kiddie pool with them in their backyard.

He was a Chicago Bears running back, strong and vibrant, a physical specimen with a warmth that lit any room he entered. He loved to eat, and sometimes emerged from a restaurant saying, “The food almost made me cry, it was so good.” He claimed to make the world’s best linguine with white clam sauce.

As the end approached, his spirit was broken. He was 60 pounds lighter with chunks of muscle missing. His ordeal left him with lumps, indentations, scars and burn marks that made his torso look like a raised-relief road map.

On June 17, 1970, the line snaked around the room, out the door and down the block at the old Michael Coletta Sons Funeral Home on 79th and Southwest Highway in Chicago. The funeral director told Joy that he never saw anything like it. They came from all over the country to pay their final respects. Mourners included Mayor Richard J. Daley, George Halas, Frank Leahy, NFL emissary Buddy Young and Giants running back Tucker Frederickson.

Everyone knew they were at the right place when they saw the wood-paneled Chrysler station wagon with the license plate BP41 parked out front.

When the funeral mass at Christ the King concluded with “Thanks be to God,” Brian’s teammates Dick Butkus, Randy Jackson, Ralph Kurek, Mike Pyle, Ed O’Bradovich and Gale Sayers guided his casket down the nave. They lifted it into the hearse, which drove to Grave 2NE in Section AM, Lot 222, at Saint Mary Catholic Cemetery and Mausoleum on 87th and Hamlin in Evergreen Park.

Advertisement

Brian was 26 years old.

“It’s still hard to come to terms with the whole thing, to have him pulled from such a young family,” says Traci Piccolo Dolby, who was 3 years old when she lost her father.

He could have been such an example to others. He could have touched so many. He could have changed the world.

No one understood why this had to happen to Brian Piccolo.

Now, almost 50 years later, we understand.

Louis Brian Piccolo grew up in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the youngest of three brothers. His Italian father Joseph and Hungarian mother Irene ran a deli. Irene was a hard woman and a domineering force in Brian’s life who loved her sports, and her beer.

Irene pushed young Brian hard. Being pushed brought out his best. When Brian played catcher in baseball, Irene stood right behind the screen so he could hear her instructions.

He was a natural in baseball and planned on being a major leaguer until Wake Forest offered him a football scholarship. His senior year in college, he led the nation in rushing yards and touchdowns and was named Atlantic Coast Conference player of the year.

His accomplishments weren’t impressive enough for an NFL team to select him in the 20-round draft, however. Brian was bewildered about not being drafted, but he didn’t lose faith.

Three days after marrying his high school sweetheart, Brian flew to Chicago to sign as a free agent with the Bears. Upon returning home, Brian sent Halas a handwritten thank you note. In a letter dated January 17, 1965, Halas responded, “Anyone with the attitude and desire that you have cannot help but make good and we are certainly looking forward to seeing you again after school is out.”

Brian spent his first season on the taxi squad. The following year, he made it on the field as a special teams player.

Brian was a popular teammate, and he gladly made many appearances in the community. He became known more for how easily he smiled than for how hard he played. And Brian played hard.

Advertisement

As the Bears reported to training camp in 1967, 159 race riots vexed the country in what became known as “the long, hot summer.” In Detroit, 43 people died, and 9,000 members of the National Guard were deployed.

In the Bears’ team picture that year, 16 of the 49 players are black. One of them is Sayers.

Halas’ son-in-law Ed McCaskey liked the idea of having a black player and white player room together, so he told Sayers he would be rooming with fellow running back Ronnie Bull. Sayers asked to room with Brian instead, and they subsequently became the first interracial roommates in the NFL.

More than roommates, they became brothers, and a symbol of what America could be.

Brian also became Sayers’ backup that season, and in 1968 he replaced him in the starting lineup after Sayers tore ligaments in his knee. In six games as a starter, Brian gained 450 rushing yards. At a point when most were skeptical about Sayers’ chances of playing again, Brian repeatedly told him how much he believed in him.

In 1969, Sayers returned and Brian went back to the bench.

One day Brian started coughing. Six weeks later, he still was coughing. On Nov. 16, after scoring a touchdown against the Falcons, Brian took himself out of the game, coughing and complaining of chest pain.

An X-ray two days later showed a spot on his lung. It was diagnosed as embryonal carcinoma, which usually occurs in the testes. On Nov. 28, a malignant tumor the size of a grapefruit was removed from his breastbone at Sloan Kettering. Chemotherapy was next.

Bears players dedicated a game to Brian, but they lost. (They only won one game that season.) When a group of them showed up at the hospital after losing, Brian, still spirited, told them, “What’s the matter with you guys? You dedicate the game to me and you can’t even win it?”

Doctors were optimistic at the time, and Brian, as was his nature, was even more optimistic. In a press conference at his home in the Beverly neighborhood in Chicago on Dec. 11, Brian declared he would return to the field.

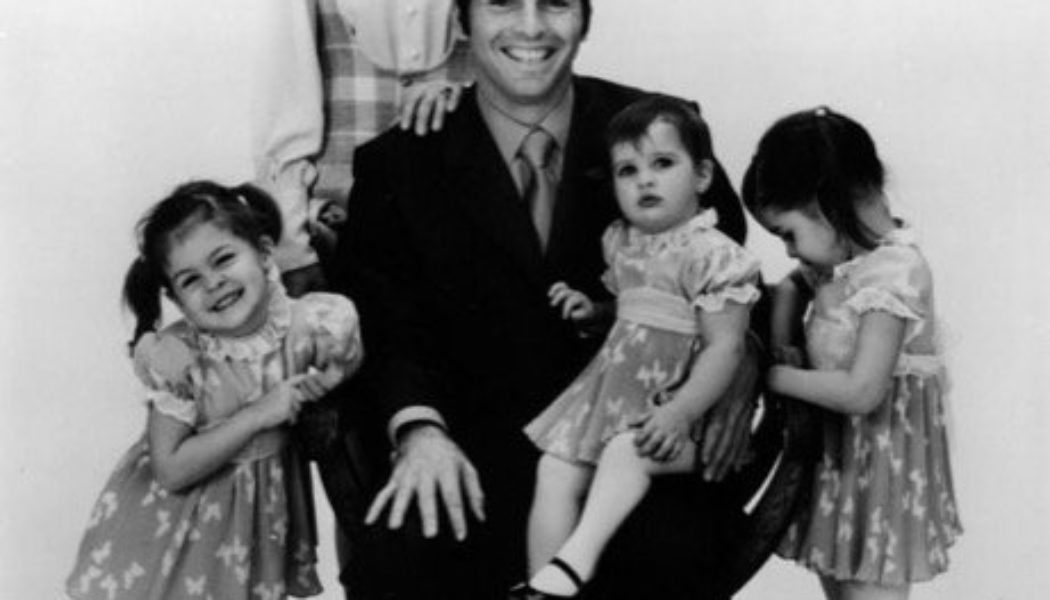

Shortly after, the family arranged to be photographed in the Chicago studio of family friend Billy DeCicco. The picture turned out to be a family treasure.

Before Brian Piccolo’s illness took a turn for the worse, the family got their photograph taken in Chicago. (Courtesy Joy Piccolo-O’Connell)

Things were going well a couple months later until Brian noticed a lump on his chest near where his tumor had been removed. On Feb. 15, he was back at Sloan Kettering. Another round of chemo was prescribed.

He was released March 10, just in time for a birthday party for Traci. And nothing was better for Brian than a birthday party for one of his girls.

“There had to be at least two dozen balloons, all blown up, and tied everywhere around the room,” Jeannie Morris wrote in the remarkable book “Brian Piccolo: A Short Season.” “Joy’s responsibility ended when the actual party began. Brian ran the whole show – the distribution of cake and ice cream, the games, the opening of presents.”

Piccolo spent hours with Morris, the journalist and wife of former Bear Johnny Morris, during his ordeal, sharing his life story and his struggle with her. It was therapy for him, and the start of something bigger.

Two weeks after Traci’s party, Brian had a mastectomy.

“Losing his breast really took him down,” Joy says. “There was this huge cave. It was horrible to look at. … He realized it was getting close to the end. That was the low point for him. I think he could see the writing on the wall.”

As Brian’s hopes and dreams faded, desperate doctors who didn’t know any better pumped poison through his body. The chemo burned his arms around the veins where it was injected. His teeth and jaw felt like he had been hit in the face with a baseball bat. There was a lot of nausea and vomiting. And his hair kept disappearing.

Brian had begun to lose his hair even before chemo treatments, and he wasn’t happy about it. He started wearing a toupee. Then Ed McCaskey asked him to attend a fundraiser for pediatric cancer. Brian showed up with the hairpiece, looked around the room at the bald kids and had a moment of clarity. He removed his toupee and handed it to McCaskey.

“He realized then there were far more important things in his life than losing his hair,” Joy says.

People were good to the family during this time. Joy stayed in Manhattan with Max and Dorothy Kendrick, friends of the McCaskeys. Dr. Beattie would give Joy a hug and walk down the hall in tears. Frederickson, who knew Piccolo from their childhood, came by with his color television set because Brian’s room didn’t have one. A steady stream of visitors included many Bears teammates, Cubs star Ron Santo, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, restauranteur Eli Schulman, comedians Shecky Greene and Phil Foster.

But nobody could make this pleasant. “Oh God, I hated New York,” Joy says. “And I will always think of New York that way. It was such an ugly time in my life.”

On April 9, doctors removed Brian’s left lung, the final insult.

Shortly after, he told Joy, “I’m done, leave me alone.”

It was around that time when Sayers was given the George S. Halas Award as the most courageous player in the NFL. At a New York banquet, Sayers accepted the trophy and gave his memorable speech.

“You flatter me by giving me this award, but I tell you that I accept it for Brian Piccolo,” he said. “It is mine tonight. It is Brian Piccolo’s tomorrow. … I love Brian Piccolo, and I’d like all of you to love him too. Tonight, when you hit your knees, please ask God to love him.”

Brian needed to see his daughters, whom he had been separated from for nine weeks. So just before Memorial Day, he and Joy flew to Atlanta, where the girls were staying with Joy’s parents. The trip was hard on Brian. He couldn’t stop coughing, and his chest felt like it was on fire. But he was able to hug his girls one more time.

Before they left Atlanta, he asked Monsignor Michael Regan, the priest who had married him and Joy, if he could receive holy communion one more time. They set up a makeshift altar in a bedroom at his in-laws’ home, and as the priest performed the sacrament, Lori, Traci and Kristi sat around their father on the bed.

Brian and Joy returned to Sloan Kettering, and soon the very real stench of death was in the air.

“The elevator door would open, and you knew someone was dying from the smell,” Joy says. “It’s something you can never forget. It was a foul smell.”

Friends and family were told to come if they wanted to see him one more time. Ed McCaskey couldn’t fly from Chicago because he had a severe ear infection, so he took the train.

Brian was struggling to breathe the night of June 15. At about 2 the next morning, Joy walked down the hall and broke down.

Then Ed McCaskey told her the nurse wanted to see her.

Brian wasn’t suffering anymore.

“That beatific, boyish, attractive smile – I never saw him without it,” Rev. Patrick J. Gleason said during the funeral mass, according to newspaper reports. “He had it the last time I saw him, the last time he was home – when he knew he would soon die.”

In her dreams, Joy sometimes saw that smile.

“Then when I’d reach out for him, he’d be gone,” she says. “I used to think he was trying to tell me that I’d figure it out.”

For a single mother with no job, there was much to figure out. But somebody always seemed to be looking over her.

When Brian was healthy, a life insurance salesman came to practice one day. Brian, for some reason Joy could not understand, purchased a substantial policy.

After his death, Joy cashed in, and the income enabled her to remain a stay-at-home mom.

Brian had a network of friends who were there with support, guidance and advice – the life insurance salesman, the lawyers, the undertaker, the guy from Royal Crown Cola, the graphics and design guy, Ed McCaskey.

Ed McCaskey speaks during a Piccolo Award press conference. (Courtesy Chicago Bears)

And then there was Halas.

It was Halas who paid for all of Brian’s medical bills and the family’s peripheral expenses, Halas who honored the remainder of Piccolo’s contract, Halas who paid for the funeral, and Halas who set up college funds for Lori, Traci and Kristi.

Halas even had a hand in making sure Joy kept her house. She had a mortgage with American National Bank, but was told the loan would not be honored because she didn’t have a regular income. It turns out Halas was on the bank’s board of directors, and he pulled a few strings.

“Nobody will ever know what he did,” Joy says. “You didn’t have to ask him for anything. It just happened. … There was nothing the Bears wouldn’t do for us. To this day, the Bears are never too busy for us.”

Halas even made sure Joy chose wisely when she started dating again. He sent a private investigator to check out a young man who she had been set up with by her Beverly neighbor.

Halas gave his OK, and three years after Brian’s death, Joy wed Rich O’Connell, the son of a Chicago cop. Rich, who made his livelihood in the ready-mix concrete business, became the husband, father, protector and provider that Joy and her girls needed. He and Joy completed their family with two sons, Tom and Mike.

These days, Joy and Rich live in Delavan, Wisconsin. Family is at the center of their lives. Joy spends much of her time caring for her 97-year-old mother Grace Murrath, who is in an assisted living facility. Murrath gave much during Brian’s illness, and now Joy gives back. Joy also is active in various charities.

She still enjoys the Bears, and the family still holds 10 season tickets. They occasionally watch a game in a suite with Virginia McCaskey, whom Joy considers a second mother.

“My life,” Joy says, “has been full. … I am blessed and I am grateful.”

Lori Piccolo, Traci Piccolo Dolby, Virginia McCaskey, Joy Piccolo O’Connell, Kristi Piccolo and Grace Murrath, Joy’s mother. (Courtesy Joy Piccolo O’Connell)

Lori works in corporate relations for The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Traci helps run Dolby Packaging with her husband John. Kristi works in business development for Dept. 11., a digital marketing agency.

Joy has 12 grandchildren. When Brian was in the hospital, he autographed a number of photos of himself. Joy still had a handful, and now the grandkids each have one.

Traci says, “Every time I look at him, I say, ‘You are my gift.’”

“I’m going to be famous one day.”

Brian said it all the time to Joy’s mother Grace, and Joy’s sister Carol.

He never said why. But he was right.

In 1971, Morris’ book drew attention to Brian’s story. Then ABC premiered the movie “Brian’s Song,” which borrowed heavily from Morris’ book, as well as the book Sayers wrote with Al Silverman, “I Am Third.”

“Brian’s Song” was the highest-rated TV movie in history up to that point. It won four Emmys, including for best dramatic program. The movie’s theme song, “The Hands of Time,” won a Grammy for best instrumental.

Kristi says everyone who meets her wants to know why she doesn’t look like James Caan, who played her father.

The girls watched the movie just once when they were children, and only made it to the part when Sayers told the team that Brian was very sick. All three girls were overcome, and Rich turned off the television.

Middle school teachers all over the country, meanwhile, were ordering copies of “A Short Season” in bulk. It was one of the only books they could get boys interested in reading.

In 1972, a school opened in Queens, New York. Students who had watched “Brian’s Song” voted to name it Brian Piccolo Middle School 53. The following year, Orr Middle School in the Austin neighborhood of Chicago was renamed. It is now called The Piccolo School of Excellence.

St. Thomas Aquinas in Fort Lauderdale, Brian’s high school, built a stadium in 1975 and named it in Brian’s honor. To this day, after every game, the marching band plays “The Hands of Time.”

In 1982, Wake Forest built the Piccolo Residence Hall for athletes.

Not far from where Brian grew up in South Florida, the Brian Piccolo Park and Velodrome opened in 1989.

The Atlantic Coast Conference has been presenting the Brian Piccolo Award every year since 1970 to the most courageous player. The Bears also have given a Brian Piccolo Award every year since 1970 to the rookie who best exemplifies the courage, loyalty, teamwork, dedication and sense of humor that Brian had. In 1993, they started giving the award to a veteran as well.

The new Halas Hall that opened this year features the Brian Piccolo Room, one of five rooms named in honor of former Bears players. Joy recently visited the space to present the Bears with the trophy that Sayers gave her husband shortly before his death. It’s tarnished and nicked up, but the Bears are treating it as a treasure and restoring it.

Shortly after Brian’s death, the Bears retired his No. 41. His jersey remains one of the team’s best sellers. Wake Forest also retired his No. 31.

Fame, as it usually does, had accidental consequences. Wonderful, accidental consequences.

In the aftermath of Brian’s passing, Halas, Ed McCaskey and Brian’s friend DiCicco put together a group of people to start the Brian Piccolo Fund. Their first initiative was a golf outing. At the time, it was believed to be the only charity golf outing in the country, and it was incredibly successful. Every NFL team sent a player. Participants over the years ran the gamut from Wilt Chamberlain to Don Rickles to the cast of “Hill Street Blues.”

In 1980, students at Wake Forest had their first Brian Piccolo Cancer Fund Drive. Thirty-seven years later, it’s still going strong. They kick off the fundraiser every year by playing “Brian’s Song” on a big screen at the Mag Patio. Students solicit donations for running laps around the quad and participating in a dance marathon.

The Piccolo Fund has raised close to $9 million. With the money from Wake Forest, the total raised in his name is closer to $12 million. The Piccolo Fund never has paid salaries, so the money initially went directly to research at Sloan Kettering, and now it goes to Rush University Medical Center. Joy and her daughters remain active in the administration of the foundation, and in organizing its events.

The money was directed toward testicular cancer for years. At the time of Brian’s diagnosis, not many survived his disease. Now, thanks in part to research funded by the Piccolo foundation, the cure rate for testicular cancer is 95 percent. Among the thousands who have survived the cancer since Brian perished are cyclist Lance Armstrong, punter Josh Bidwell, figure skater Scott Hamilton and baseball player John Kruk.

The Piccolo Fund is now directing funds to researching cures for breast and ovarian cancer.

Brian loved Joy’s sister Carol, who was afflicted with cerebral palsy. When they were teenagers, he took her to basketball and football games, navigating her wheelchair through crowds. After Brian started traveling for football, he sent Carol a postcard from wherever he went. And he promised Joy’s mother that he would always take care of Carol.

Carol lived at Clearbrook in Rolling Meadows for 30 years until her death in 2017 at the age of 68. The Piccolo Fund has donated 10 percent of its money to Clearbrook, which supports people with disabilities.

Brian’s time was too brief, his demise too painful.

Virginia McCaskey has said she questioned the will of God one time in her 96 years – when she watched Brian dying.

But Brian did not die in vain.

“It’s powerful, the number of people who have approached us and said, ‘I’m alive because of your dad,’” Traci says. “If we need a reason for why it happened, that’s it.”

That’s it. Brian Piccolo had to die so others could live.

The author of this story is a testicular cancer survivor. To learn more about The Brian Piccolo Fund, or to donate, go to https://www.brianpiccolofund.org

(Top photo of Joy and Brian Piccolo at his Bears signing ceremony in December 1964: AP Photo)

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity

![The 50 best Western movies ever made [They got No. 1 right, but No. 25 deserves a higher rank]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/the-50-best-western-movies-ever-made-they-got-no-1-right-but-no-25-deserves-a-higher-rank-327x219.jpg)