There is a letter, undated but composed around the year 1646, written under obedience to his superiors, by Father Isaac Jogues, Jesuit priest and martyr. It concerns a Jesuit Brother who would also become a martyr: René Goupil.

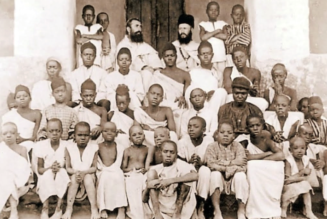

René arrived in the New World from Europe in 1640. For the next two years, as a Jesuit lay missionary, he worked both in humble manual labor in the Jesuit house and as a surgeon in the hospitals of Quebec. Father Isaac notes that Rene “totally submitted himself to the guidance of the superior of the Mission, who employed him two whole years in the meanest offices about the house, in which he acquitted himself with great humility and charity. He was also given the care of nursing the sick and the wounded at the hospital, which he did with as much skill — for he understood surgery well — as with affection and love, continually seeing Our Lord in their persons.”

In 1642, René set out for the Huron mission with Father Isaac, whose constant companion and disciple he would remain until his death. The Hurons were an Iroquoian-speaking tribe who were living along the Father Lawrence River. At the time the tribe needed the services of a surgeon. René desired to join the Huron mission and for this reason his request to leave Montreal was granted. Father Isaac observed René’s joy: “I cannot express the joy which this good young man felt when the Superior told him that he might make ready for the journey. Nevertheless, he well knew the great dangers that await one upon the river …”

Father Isaac and René departed Montreal for the Huron on Aug. 1, 1642, the day after the feast of St. Ignatius Loyola. The following day, the two missionaries were captured by the Iroquois, who were fighting the Hurons at the time. Father Isaac wrote of this moment and of René:

On this occasion, his virtue was very manifest; for, as soon as he saw himself captured, he said to me: ‘O my father, God be blessed; he has permitted it, he has willed it — his holy will be done. I love it, I desire it, I cherish it, I embrace it with all the strength of my heart.’” The priest heard René’s confession and gave him absolution since they did not know “what might befall after our capture.

While being forced to march to an unknown fate, the priest marveled at René’s presence of mind and at how his fellow prisoner “was always occupied with God. His words and the discourses that he held,” the priest wrote, “were all expressive of submission to the commands of the Divine Providence, and showed a willing acceptance of the death which God was sending him.” Father Isaac recounted how this Jesuit lay missionary saw his life in general, and this the moment of capture in particular, as a holocaust.

The humility and obedience that René rendered to those who had captured him astonished Father Isaac. Sometimes the priest suggested to René that he might try and escape but, of this suggestion, the priest wrote: “He would never do so — committing himself in everything to the will of Our Lord, who inspired him with no thought of doing what I proposed.”

Born in 1607, René Goupil was a native of Anjou, France. While still a youth he discerned a vocation to the Jesuits and asked to enter the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Paris. But poor health prevented him from going forward to receive Holy Orders. His physical frailty did not prevent him, however, from following his vocation as a Jesuit missionary. And when his health improved, he volunteered to serve in New France as a donné — in French, “given” or “one who offers himself.”

Eventually, the captives came to a village where a shower of blows from clubs and iron rods rained down upon the captives. Father Isaac wrote that René showed “a most uncommon patience and gentleness” — even when Father Isaac looked over toward his companion and saw that he was covered in bruises.

“Hardly had he taken a little breath,” continues the priest, “when they came to give him three blows on his shoulders with a heavy club, as they had done to us before. When they had cut off my thumb — as I was the most conspicuous — they turned to him and cut his right thumb at the first joint — while he continually uttered, during this torment: ‘Jesus, Mary, Joseph.’’

During the next six days, the men were held captive in Iroquois cabins. Father Isaac wrote that René again “showed an admirable gentleness”. He was burned by coals; hot cinders were thrown upon his body at night as all the while he was bound flat upon the earth. For the next six weeks, they were held captive by the Iroquois. The priest sensed the peril of the situation — something to which René appeared oblivious.

“He did not quite realize the danger in which we were. I saw it better than he, and this often led me to tell him that we should hold ourselves in readiness.”

The priest said: “My dearest brother, let us commend ourselves to Our Lord and to our good Mother, the Blessed Virgin; these people have some evil design.”

The two men did indeed commend themselves to God, “beseeching him to receive our lives and our blood, and to unite them with his life and his blood for the salvation of these poor peoples.” And they then began to recite the Rosary. When they had completed four decades, the priest saw an Iroquois draw a hatchet which had been “held concealed under his blanket,” and he wrote how it was this weapon that dealt “a blow on the head of René, who was before him.” The layman fell motionless, pronouncing the holy name of Jesus.

At the blow, I turned around and saw a hatchet all bloody; I knelt down, to receive the blow which was to unite me with my dear companion; but, as they hesitated, I rose again, and ran to the dying man, who was nearby. They dealt him two other blows with the hatchet, on the head, and dispatched him — but not until I had first given him absolution, which I had been wont to give him every two days since our captivity; and this was a day on which he had already confessed.

The day of martyrdom was Sept. 29, 1642. Father Isaac expected to be martyred in the same way as René but this did not happen.

“Indeed, I passed several days,” he wrote, “on which they came to kill me; but Our Lord did not permit this, in ways which it would be tedious to explain. The next morning, I nevertheless went out to inquire where they had thrown that blessed body, for I wished to bury it, at whatever cost. Our Lord gave me courage enough to wish to die in this act of charity.”

After René was killed, however, the children of his murderers stripped his body and then dragged it with a rope about the dead man’s neck, into a torrent that passed at the foot of the village. It was there the priest found the body. He was shocked to see that “dogs had already eaten a part of it. I could not keep back my tears at this sight; I took the body, put it beneath the water, weighted with large stones, to the end that it might not be seen. It was my intention to come the next day with a mattock, when no one should be there, in order to make a grave and place the body therein.”

The next day, however, the priest returned to where he had placed the body, only to find it gone. “How many tears did I shed, which fell into the torrent,” he wrote, “while I sang, as well as I could, the Psalms which the Church is accustomed to recite for the Dead.” Later he was to discover that the body had been dragged into a nearby wood. It was there he “found the head and some half-gnawed bones, which I buried with the design of carrying them away. … I kissed them very devoutly, several times, as the bones of a martyr of Jesus Christ.”

Subsequently, Father Isaac was keen to stress that the title he had used here — “martyr of Jesus Christ” — he had conferred on René not simply because he had been “killed by the enemies of God and of his Church, and in the exercise of an ardent charity toward his neighbor” but because “he was killed on account of prayer, and notably for the sake of the Holy Cross.” For, as the priest later explained, René was held prisoner in a cabin “where he nearly always said prayers — which little pleased the superstitious old man who lived there.”

One day, seeing a little child of three or four years in the cabin, “with an excess of devotion and of love for the Cross, and with a simplicity which we, who are more prudent than he according to the flesh, would not have shown,” René “took off his cap, put it on this child’s head, and made a great sign of the cross upon its body. The old man, seeing that, commanded a young man of his cabin, who was about to leave for the war, to kill him — which order he executed, as we have said.”

Father Isaac was adamant that it was because of this Sign of the Cross that René had been killed.

René Goupil was canonized June 29, 1930, by Pope Pius XI. His feast day is Oct. 19.