Hey everybody,

Today is the feast of St. Simon Stock, the 13th-century Carmelite who, by tradition, received from the Blessed Virgin the brown scapular which forms part of the Carmelite habit, and which — in smaller form — is worn daily by non-Carmelite Catholics around the world (including me!).

The scapular represents the filial piety of Catholics who have entrusted themselves to the protection of Our Lady — it is a sign of receiving Mary as a mother, and asking for her intercessory prayers.

It became a popular devotion beyond the Carmelites in the 16th and 17th centuries, and remains one today — and it probably helped that Pope John Paul was devoted to the scapular sacramental, reportedly asking in 1981, after an assassination attempt, that doctors leave his scapular around his neck while they operated on his body.

Of course, there are people who criticize the scapular as a kind of talismanic devotion — taking the so-called scapular promise (“whoever dies clothed in this scapular shall not suffer the fires of hell”) literalistically, instead of understanding it as a way of talking about persevering in the spiritual life.

It would be a mistake to imagine that one can die very far from God, in a pile of sin and depravity, and be taken up to heaven because one has worn the right wool squares around one’s neck. But I don’t know too many people who actually think that’s what their scapular is about.

Taken properly, as a sign of consecration to Christ through the maternal intercession of the Blessed Mother, the scapular can be a physical sign of the way in which, as John Paul II put it, “devotion to [Mary] cannot be limited to prayers and tributes in her honor on certain occasions, but must become a ‘habit,’ that is, a permanent orientation of one’s own Christian conduct, woven of prayer and interior life, through frequent reception of the sacraments and the concrete practice of the spiritual and corporal works of mercy.”

JPII added: “In this way the scapular becomes a sign of the ‘covenant’ and reciprocal communion between Mary and the faithful: indeed, it concretely translates the gift of his Mother, which Jesus gave on the Cross to John and, through him, to all of us, and the entrustment of the beloved Apostle and of us to her, who became our spiritual mother.”

Whether you’re a scapular wearer or not, let the feast of St. Simon Stock remind us to make our devotion to Mary a “habit,” a “permanent orientation of … Christian conduct,” through the sacraments and the works of mercy.

St. Simon Stock, pray for us.

The news

Bishop Jean-Marc Eychenne of Grenoble-Vienne, France, shows his identity card. Screenshot from Église catholique en France YouTube account.

The ID card system has gotten some pushback in France, with some victim advocacy groups calling it a publicity stunt, and saying that it’s been rolled out in place of more systematic safeguarding policies needed in France.

I don’t know about all that.

But I do know that in the U.S., there exists a cumbersome, time-consuming, and expensive (in terms of personnel) back-and-forth process between dioceses for checking to see whether a cleric is a priest in good standing, who has faculties, and who has completed the safe environment trainings and background checks required for ministry.

When priests go out of town for weddings, retreats, vacations, or to fill in for a friend, there is a lot of paperwork going on between curias to make sure things are in order. A digitized system that would simplify that process would save priests a lot of headaches, and save chanceries a lot of time and money.

Of course, much like the current “letter of suitability” system, the digital ID card system is only as good as its users — if chanceries weren’t honest about a priest’s status, the card system wouldn’t fix that. And if chanceries didn’t update statuses in their databases, well, the card system wouldn’t be especially useful. But there are “user error” problems with the current approach as well, and sometimes they’re caused by the sheer volume of letters being handled in a vicar for clergy’s office — a volume that would be considerably reduced by this system.

It would be foolish to think that this system could replace other needed safeguarding reforms — as the victims’ advocates in France pointed out. But while it can’t solve all problems, it could solve some problems — and I know a lot of clerics hoping the bishops of the U.S. will take up a similar system soon.

Read all about France’s efforts, right here.

“We are witnessing in recent weeks a Church in which leading men are cementing their power, refusing developments, and further deepening the rifts between the Church and the world,” the Zdk’s Irme Stetter-Karp said earlier this month, complaining about the Vatican’s refusal to endorse a resolution calling for lay preaching at Masses.

“I am angry and shocked,” Stetter-Karp declared. “But today more than ever it is clear: This Church as an absolutist system of power must come to an end.”

In an analysis last week, Luke Coppen broke down the ZdK’s efforts to obtain a permanent share of decision-making power within the Catholic Church in Germany — and its escalation of confrontational rhetoric after the Vatican didn’t endorse synodal way proposals.

Interesting, of course, is that German bishops have to date seemed to fall into line with whatever Stetter-Karp pushes for in Germany. But as they’re forced into a corner, it’s not clear they’ll continue “accompanying” the ZdK — and their pushback would mark a major sea change for ecclesiastical dynamics in Germany.

Read all about that, right here.

—

The Vatican City State got on a Saturday a new constitution, promulgated by Pope Francis, and making a number of interesting reforms. Most headlines about the new law have focused on the fact that lay people can now serve on the city-state’s governing commission.

But most striking at The Pillar is that the new constitution talks about the exercise of authority in a very unusual way — removing all references to ordinary governance power, and focusing on governance “functions,” exercised in cooperation with the pontiff.

That might seem like pedantic semantics.

But amid a major Vatican debate about lay people and the “power of governance” in the Church, this revised rhetoric in the fundamental law of Vatican City is a big deal. But — what exactly does it mean?

—

Pope Francis has told journalists in recent months that he’s hoping to go to his native Argentina next year.

In 10 years of papacy, the pontiff has not yet been home to his country — and the reasons why are pretty complicated, actually. And, in fact, 2024 isn’t chosen at random: there’s a pretty good set of reasons why that might be the most sensible year for the pope to return home.

But to understand much of that, you’ve got to understand something about Argentine politics, and the pope’s long-standing tensions with various politicians, of various parties.

So our Latin American correspondent, Edgar Beltran, took a very deep dive into some of Francis’ history in Argentina — talking with a number of experts on the subject — to explain why the pontiff has delayed his homecoming.

Sources close to the Dicastery for Bishops confirmed that Pope Francis decided last month to request Stika’s resignation, after reviewing the results of a Vatican-ordered investigation into the bishop’s management.

Of course, the Knoxville diocese has not commented on our reporting, and it remains to be seen whether Stika will actually tender his resignation. If he doesn’t, it could take some time for a difficult situation in Tennessee to resolve. But our reporting indicates that a long saga in the diocese is coming to its end game.

My suspicion is that Bishop Mark Spalding of Nashville will be appointed to temporarily lead the diocese if, and when, Stika makes his exit.

And, if you’ve forgotten how exactly it started, you can read our lengthy May 2021 profile of Stika — which gives a rather comprehensive view of the man himself, even while we’ve uncovered considerably more about his leadership since its publication.

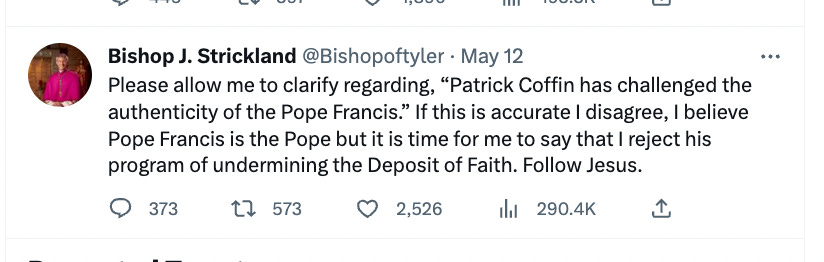

Did +Strickland do a schism?

Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, attracted some attention this weekend, when on Friday night he tweeted that “I believe Pope Francis is the Pope but it is time for me to say that I reject his program of undermining the Deposit of Faith.”

There is a backstory to the tweet, which involves Strickland signing on to participate as a lecturer in a kind of online course organized by a sedevacantist named Patrick Coffin, and then pulling out once he learned it was a sedevacantist affair.

But the backstory isn’t important right now, or at all, actually.

To many people, though, it does seem important that a sitting diocesan bishop accused the pope of advancing a “program undermining the Deposit of Faith.”

The “deposit of faith” constitutes the whole of sacred revelation, as contained in Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition, to be interpreted by the Church’s magisterium — so it’s no small potatoes for a sitting diocesan bishop to say the pope opposes that sacred deposit.

I was reminded by the tweet, to be honest, of some of the more fiery columns written decades ago by Milwaukee’s Archbishop Rembert Weakland in opposition to Pope St. John Paul II’s Curia, with whom Weakland disagreed on just about everything.

I don’t think +Strickland would appreciate being compared to +Weakland, but I can’t think of another American bishop who has so openly and directly expressed such vehement opposition to a pope’s leadership in a public context.

Now, let’s be real for a minute, OK? Really real.

There are a lot of Catholics, bishops among them, who think that Pope Francis’ approach to governance and teaching in the life of the Church is counterproductive, theologically flawed, or inimical to the flourishing of the Gospel. There were a lot of Catholics, bishops among them, who thought that about JPII or Benedict XVI’s leadership, or about that of Paul VI and John XXIII before them.

The pope is a sign and agent of unity in the Church, but he fosters that unity through faith, sacraments, and governance, not his own personal priorities or opinions.

This is a big Church, and we’re not all going to agree — so it shouldn’t be a source of scandal that some bishops think the Church’s pastoral life should be going in a very different direction than the pope is taking it. Especially in the modern era, when the personality of the pope looms so large, and seems to shape an office which once dwarfed its occupants, it can hardly be a surprise that a cadre of bishops disagree with the rhetoric, policies, or priorities of the Roman Pontiff. There’s no sin in that, so far as I can tell.

And there are probably a fair number of bishops today who basically agree with what Strickland had to say, even if they think he said it inelegantly, at best.

But a bishop has the responsibility of both leading his own people, and of building up unity in the life of the entire Church — of encouraging filial piety toward the pope as a universal shepherd and the principle of unity, and of encouraging obedience to him.

A bishop also has a responsibility to assure Catholics of the unique charism of the pope to teach, and of the Lord’s promise to protect the Church from error or apostasy, even if not to protect the Church from the imprudent choices of her leaders, or of the consequences of those choices.

While Strickland didn’t expressly encourage disobedience to the pope, you’d be hard-pressed to argue that language about “rejecting” and “undermining” is going to help Catholics who feel discouraged or confused at the moment to find their footing — or remind them about the charismatic infallibility of the papacy which acts as a kind of safeguard for the deposit of faith itself.

In that sense, it is a scandal if a sitting diocesan bishop made it harder for Catholics to find the proper disposition at a difficult moment in the Church’s life, or if he enflamed the passions of Catholics, undermining their ability to accept the primacy of the pope as an article of both faith and practice.

Now, the bishop might say there’s a reason for his rhetoric. I asked him for an interview on Monday to explain himself, but he declined to give that interview — so we’re left without his elaboration.

I have noted before that Strickland seems to speak before he thinks at crucial moments, and that while he’s sometimes revered as a straight-shooting hero, there are consequences to that kind of thing, and they often lead to confusion.

Still, while I’ve seen commentators and reporters suggest that Strickland’s tweet on Friday constitutes a kind of schism, I don’t think that’s so.

Schism is the “refusal of submission to the Roman Pontiff, or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him.”

It generally means a formal act of rejection – excluding the pontiff from the Eucharistic prayer, for example – or an act of disobedience to an actual directive from the pope. So while people might argue Strickland is in the proximate occasion of schism, I can’t see how he’s actually committed the canonical crime.

There is another canonical crime, though, that might be applied to Strickland’s rhetoric:

Canon 1373 establishes that “a person who publicly incites hatred or animosity against the Apostolic See or the Ordinary because of some act of ecclesiastical office or duty, or who provokes disobedience against them, is to be punished by interdict or other just penalties.”

It could be plausibly argued, I think, that Strickland’s tweet might well provoke disobedience against the Apostolic See, given that it talks about a kind of rejection of the pope’s leadership — or suggests as much.

We discussed c. 1373 at The Pillar yesterday, with Ed of the opinion that the Holy See might very well sanction Strickland, in light of the canon, for the scandal of his tweet.

Ed argued that bishops have been removed for less — pointing out that the bishop of Arecibo, Puerto Rico, was removed from his office last year for, effectively, some disagreements with his brother Puerto Rican bishops.

But that bishop was reportedly removed after considerable lobbying by influential churchmen who didn’t like his influence on the Church in Puerto Rico. And I don’t think the Holy See will have much response to Strickland’s tweet.

In the first place, the Vatican is still enough of the old school that while a magazine or journal article might rank as important, a tweet seems to many officials like some ephemeral bit of noise on the internet, unimportant, because it’s not understood.

But more than that, Pope Francis’ approach to overt criticisms of his leadership — whether from left, right, or center, is to ignore them — to deprive his critics of the oxygen they’d gain from his attention. Whether a particular criticism is valid or not is immaterial to him — the pope has demonstrated that he prefers to freeze out his critics, as he’s done in Germany, rather than respond with defenses or overt sanctions.

While I am certain the Holy See will make life difficult for the bishop of Tyler, by a thousand kinds of administrative and bureaucratic coldness, I think Strickland was probably already on the list for that kind of treatment in Rome.

Furthermore, I don’t think there’s anyone to lobby for his removal, or for any kind of sanction against him, for that matter.

If the American churchmen influential in Rome are asked their opinions, I suspect they’ll say they see Strickland’s rhetoric as a problem. But I don’t think they’ll stick their necks out too far over the issue.

I suspect those influential American churchmen in Rome realize they only have so much political capital for these kinds of things, and they don’t perceive Strickland as a major obstacle to achieving their goals for the life of the Church.

They might be bothered by his impertinence, sure, but I don’t think anyone in ecclesiastical leadership takes him seriously enough to push to get this on the pontiff’s desk.

In the Church, there is a certain kind of latitude extended to people perceived as harmless-seeming zealots, especially if they lack very much influence on their brother bishops. I suspect that’s how Strickland will be perceived in Rome, unless American cardinals push the issue.

In short, I’ll be very surprised if the pope makes any move regarding Strickland.

Again, I’m not saying I’ve got an opinion on what should be done about him — I know I’ll soon get emails about why my opinion is wrong on Strickland — it’s just my read of the situation itself.

Marshall Matters

In a surprise move last week, Catholic YouTube celebrity and internet provocateur Taylor Marshall announced that he was running for president.

Of the United States of America.

Now, in our little corner of the world, Marshall is not an unknown commodity. The guy has some half-a-million subscribers on YouTube, wrote a book hypothesizing about various infiltrations of the Vatican, developed a friendship with Archbishop Viganò, and paid the expenses of the guy who threw “the statue” in the River Tiber during the 2019 Amazon Synod.

He’s also the guy who said just a few months ago that the U.S. government is running an elaborate psyop on the American people to distract us from the possibility of demonic extraterrestrial aliens — or something very close to that.

Marshall is a former Anglican curate who became a Catholic, who once had a little apostolate selling catechetical materials, and whose messaging gradually became more provocative, and less connected to reality, as his YouTube audience grew.

He built an audience while rejecting at various times the legitimacy of the Church hierarchy and Vatican Council II, and, when the moment struck, allied himself with the political conspiracy theorism and biblically apocalyptic rhetoric surrounding the “Stop the Steal” movement.

He is, to my mind, best understood as a kind of religious entertainer, a performance artist, floating often outlandish conspiracy theories and provocative opinions, while managing to connect, in some down-to-earth way, to the real neuralgia about Church and state experienced by a real-life swath of Catholics.

He’s not unlike alt-right polemicist and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, actually — and as it happens, Marshall’s been interviewed as a Vatican “expert” on Jones’ Infowars.

If you’re not down with that kind of thing, let me say Marshall shouldn’t be written off entirely, because, the fact is, he has an audience, and makes a very nice living giving hot takes on the Church, selling books about freemasons and invented conspiracy theories, and portending some coming doom for America and the Church.

It is easy to make fun of Marshall’s schtick. But I think his audience deserves more careful consideration. They matter to me. They’re people who practice the faith, and have concerns and anxieties — people who went looking to make sense of things, and found this dude on YouTube promising he’s got all the answers.

That audience, by the way, exists in real life — when I speak at parishes, seminaries, or diocesan events, I’m often asked what I think of Marshall’s book, or encouraged to check out his YouTube channel — and often enough, by clerics.

And I promise you — this week we’ll see canceled subscriptions, and we’ll get nasty emails, from people who think I fail to appreciate Marshall’s prophetic genius.

While I don’t think Marshall evinces a firm or cogent grasp on issues in the Church, or talks about them sincerely or responsibly, his popularity says something about the unease many Catholics feel about the state of the Church, and about their place in a rapidly changing world — “not an epoch of change,” Pope Francis says, “but a change of epoch.”

And in a certain way, Marshall’s place in the U.S. Church is not all that unlike that of Fr. James Martin — and the popularity of both of those men is instructive.

Like Fr. Martin, the fact that Marshall has a (big) audience tells us some important things about what different swathes of Catholics value, what they fear, and what they’re looking for — even if both men take advantage of that audience, or exploit it to pursue their own (radically different) agendas.

Marshall’s popularity, like Martin’s, strikes me as a kind of funhouse mirror, through which something can be gleaned — with enough filters to straighten the image — about the state of the Church. And it seems to me we should be willing to look.

In fact, if we really want to learn what disenfranchised Catholics think about the Church, we might learn more from the comments in Taylor Marshall’s YouTube videos than we can from all the synods on synodality that every synoded synodally.

And I, for one, think that’s useful.

But Taylor Marshall is not a known commodity outside our small corner of the world.

And let’s just be clear about something.

Taylor Marshall is not going to be the president.

Taylor Marshall will not be president.

He won’t be.

I’m pretty sure that he doesn’t even want to be president.

With that out of the way, I should say that I’m an admirer of third parties and the role they play in American political life, and I think it can be perfectly legitimate to vote for them. I think democracies are healthier without a duopoly locked in enduring combat, when small parties can play key roles in forming coalition governments, and when new ideas have room to move forward.

I think the Democrats and Republicans have done well enough in this country at capturing the whole of our political imagination, and the perpetuity of binary power transfers, such that most of us believe there are only two meaningful options for voting.

The guidance of the Church affirms the legitimacy of choosing the candidate who you think would be the best, even if he won’t win — or even of not voting in a particular race. But when election year rolls around, I hear a lot of well-meaning Catholics say that anything but a vote for Candidate X is really a vote for Candidate Y — or vice versa.

We even hear that from a swath of well-meaning pulpits.

I don’t think the mathematical or moral assessment on that actually checks out, but you hear it in election years, pretty often — “If you don’t vote for Our Guy, you’re voting for the Other Guy. And the Other Guy is pure evil, so you’ve got to vote for Our Guy. And this is the most important election of our lifetime. Again.”

The Church teaches clearly that voting for certain candidates, with inhuman policy agendas, is morally abhorrent, or that one needs rather significant “proportionate reasons” to overcome the monstrosity of their agendas. And it teaches that when all candidates have morally abhorrent agendas, you can choose one who “deemed less likely to advance such a morally flawed position and more likely to pursue other authentic human goods.”

The Church doesn’t teach that if you don’t vote for one of the frontrunners, you’re somehow voting for the other frontrunner. But come election time, you’ll hear a lot of that, with fervent conviction, from lots of Catholics.

And, in fact, in elections past, it was the kind of the thing you’d hear from Marshall’s audience, or from the man himself, as when, for example, he served in 2020 as a prominent member of Catholics for Trump.

So I’m interested to see whether Marshall’s presence as a “candidate” — he is not, as of yet, among the 727 Americans who have filed paperwork with the Federal Elections Commission declaring their candidacy for president — will change that discussion for some Catholics.

Of course, I can’t speculate about why Marshall is running for president. Or, I can, but it wouldn’t be charitable.

But I will say, sincerely, that if the candidacy of a polemicist YouTuber and “Infiltration” expert opens up discussion about breaking free from a consequentialist moral calculus, one mandating people vote for a candidate they just can’t stomach — well, I’m glad for the conversation, at least.

And did you know that 727 Americans have filed paperwork to declare themselves candidates for 2024?

This is one hell of a country, guys.

It’s not the celibacy

Finally, we covered last week the scandal of Fr. Alfonso Pedrajas, a Spanish Jesuit who served in Bolivia, and whose posthumously discovered journals revealed that he had committed serial abuse of minors, and that his ecclesiastical superiors had seemingly covered it up.

Pedrajas’ journals are sobering and sickening reading, by any standard.

Well, as the Bolivian bishops respond to the scandal, one took to the radio last week, to say that as “changes have to be made,” one of them is for the Church to ordain married men to the priesthood.

According to Bolivian radio network Erbol, Bishop Eugenio Coter argued that allowing married men to be ordained priests could be part of the solution to the problem of sexual abuse in the Church, since, he reportedly argued, marriage helps a person to develop an integrated sexuality, and provides companionship.

Please allow me to editorialize for a moment: Bishop Coter seemingly has rather profoundly misunderstood the dynamics of pederastic and pedophilac child abuse in any context. Marriage would not stop pederastic child abusers from committing abuse. In fact, as data from other public institutions shows us repeatedly, it doesn’t. And indeed, the most typical place for a child to be abused is in his extended family or among family friends, most of whom are not likely celibate.

Of course, I’ve seen it argued that there is a greater likelihood that married men will have a mature, integrated, and chaste sexuality than celibate men. I don’t see any reason to think that’s true — in fact, I don’t think it’s true. But even if it were, allowing for the possibility of married men wouldn’t, by itself, screen out from the priesthood men with the propensity or disposition to be abusers. Better screening, scrutiny, evaluation, and formation processes would do that, with the knowledge that sacred ordination, or admission to religious life, shouldn’t be offered to everyone who seeks it.

It is a demeaning view of marriage — and of women — to suggest that if only priests could be married, abuse would not happen. There is no evidence to suggest this, as experts in abuse and safeguarding have often argued.

Clerical celibacy has a long and rich theological and spiritual history in the West. It is not absolute, of course — deacons can be married men, as can members of the Church’s Anglican ordinariate. But celibacy is a disciplinary, not a doctrinal matter, and the Church could allow for more married men to become priests in the West. Certainly, there are prelates who think that’s a good idea.

But whatever their reasons, the notion that ending clerical celibacy would eradicate abuse is a red herring. At least as far as I can tell — If you think otherwise, let me know in the comments. I’d be interested to read your view.

Souls in the game

And to leave you with something decidedly more positive, here’s a promo for “Souls in the Game,” a forthcoming documentary on the basketball team at Saint John’s Seminary in Boston.

The full documentary comes out later this month. And since my beloved New Jersey Devils have been eliminated from the NHL playoffs, I know that all of you will have time to watch this film.

If you can, guys, please share The Pillar with your friends.

If you haven’t yet, please subscribe, support our work, or give a gift subscription:

And most important, please be assured of our prayers. And please pray for us — we need it!

In Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Comments 91

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews