LONDON — Katryn Wehr, Ph.D., has come to London from her home in Minnesota to speak about the work and life of the British writer Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957).

“She is just so interesting,” begins Wehr. “Sayers is an inspiring author because she was full of life and interested in so many things. She wrote mystery novels, poetry, plays, essays, speeches and translated Dante.”

Wehr is keen to point out the many literary genres in which Sayers excelled. Today what is less well remembered, however, she reveals, is that she was a devout Anglo-Catholic — that is, an Anglican with decided Catholic sympathies — and an effective Christian apologist who influenced C.S. Lewis in his use of mass media, including radio.

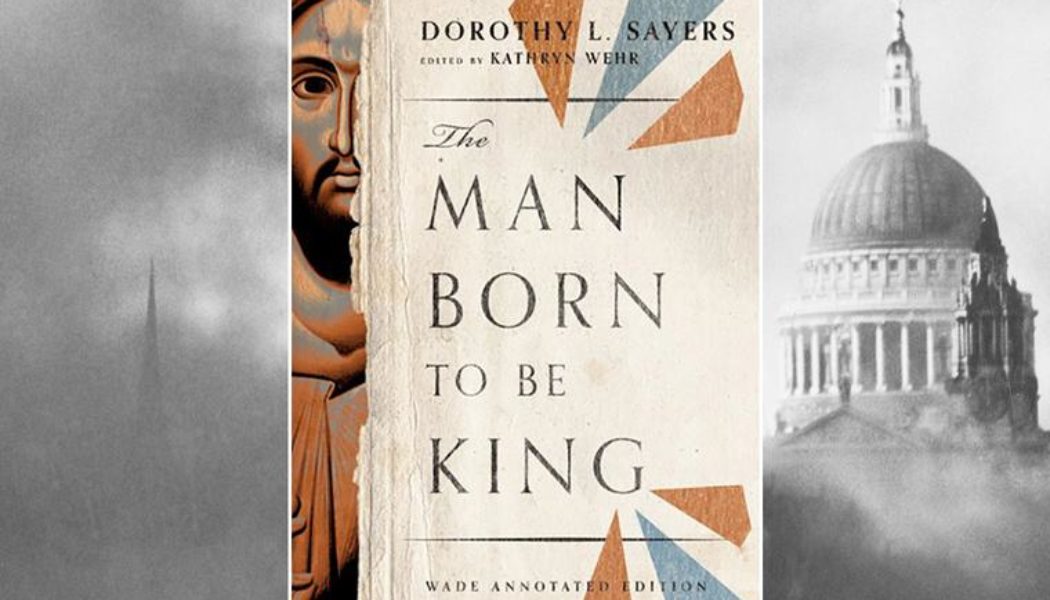

Wehr has edited the recently published The Man Born to Be King, Wade Annotated Edition (IVP Academic). Originally produced and broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) during the Second World War, The Man Born to Be King is a radio drama consisting of 12 plays on the life of Our Lord. The opening play of the cycle was first broadcast by the BBC in December 1941, and the subsequent plays ran at four-week intervals, ending on Oct. 18, 1942. The text of the whole cycle was published in 1943.

Needless to say, the appearance of this new critical edition of the plays has delighted Sayers aficionados. One reviewer summarized its achievements by saying it offers “insights into Sayers’ vocation as a Christian writer” and that, “along the way, we learn how dogma can be creatively communicated in drama.”

For Wehr, this edition of The Man Born to Be King has been a labor of love.

She first encountered the plays while studying theater in college and admits that this introduction had her “hooked.” Thereafter, she chose the 12 plays as the subject of her doctoral research at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. This new, and first, annotated edition is, she explains, “the fruit of my research on Sayers’ use of Scripture and theology within the plays, but with that information presented in a reader-friendly way, in footnotes and sidenotes.” The book is akin, she suggests, to a “backstage tour of the plays.”

Wehr works as managing editor of Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, an interdisciplinary quarterly committed to exploring the beauty, truth and vitality of Christianity, particularly as it is rooted in and shaped by Catholicism, based at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. Given her work as editor of this journal, and also that she is a self-confessed Anglophile, it is perhaps not surprising that Wehr found in Sayers a literary companion. Brought up a devout evangelical Christian, by the time Wehr first visited England as a mature student, she found that she had moved a long way from the Baptist faith of her youth. In time, she would become an Anglican, but that would not be the end of that journey. During the 2016 Easter Vigil at St. Andrews, Scotland, she was received into the Catholic Church.

Today, Sayers, like her contemporary and friend G.K. Chesterton, is best remembered as a writer of detective fiction. What Father Brown is to Chesterton, Lord Peter Wimsey is to Sayers. Yet viewing either Chesterton or Sayers solely, or chiefly, as creators of literary sleuths, limits and obscures the contribution to the intellectual climate of their times. This is particularly so with regard to the deeply held Christian beliefs of both writers. Chesterton was a Catholic convert from Anglicanism and Sayers was a devout Anglican; both were Christian apologists, combining sincere Christian conviction with an ability to communicate its truth to the general public.

Chesterton died in 1936, and the medium of his apologetics was limited largely to newspapers, magazines and books. Sayers, by contrast, while writing in the 1930s and ’40s, had access to a new medium through which to evangelize, namely, the radio.

In 1938, she was asked by the BBC to write a radio play on the Nativity. This she duly did, and He That Should Come was broadcast to the nation on Christmas Day. That proved such a success that the BBC commissioned Sayers to write a series of plays on the life of Christ. She consented to do so, on the condition that Our Lord would be one of the characters and that the radio plays should be realistic in tone and contemporary in use of language, with her characters not “allowed to talk Bible.” In short, she wanted to ensure that the voices should sound modern and relevant, as opposed to archaic and pietistic. The BBC agreed to her conditions. And so she got to work on the cycle of plays that would come to be known as The Man Born to be King.

In the 1930s, across the British Isles, the medium of radio had become the foremost mass media. By then, with the advent of the BBC in 1922, wireless set ownership and radio listenership had grown at a remarkable pace, so much so, that, by 1939, it is estimated that there were 9 million wireless sets in Britain, with the BBC, then the only broadcaster, reaching an estimated three-quarters of the nation’s 48 million people. Radio in the 1930s might, with some justification, be described as the pre-war internet.

It was to this mass audience, during the dark days of 1941, when Hitler’s Luftwaffe was bombing British cities, that Sayers was communicating perhaps the most fundamental Christian revelation: namely the story of the incarnation, death and resurrection of Our Lord, as recounted through The Man Born to Be King.

As it transpired, the only opposition to the play broadcasts came from some hidebound Christians, who were shocked at any portrayal or characterization of Our Lord outside the Scriptures. But they proved to be in the minority, as immediately after the broadcasts, the BBC received a flood of letters testifying to how deeply the plays had impressed listeners. Those with faith felt it strengthened and intensified by a radio-play presentation of a story they had heard many times before; others felt moved because they had never before heard the Gospel in their lives.

“It was The Chosen of the 1940s,” observes Wehr. By any measure, the BBC considered the broadcast and its reception a great success, especially coming, as it did, at a time of national crisis as the war dragged on.

Sayers brought to the work her faith, but, perhaps as importantly, she also brought her talents as a storyteller with a creative flair for presentation. By the early 1930s, she had written several stage plays and was well acquainted with what worked for theatrical performances. With a novelist’s sense of shaping a story, combined with a playwright’s sense of the dramatic, she dramatized what has rightly been described as “the greatest story ever told” for a mass audience, on the most far-reaching medium then available. From the point of view of Christian apologetics, this was an incredible opportunity — to which Sayers rose and in which she triumphed.

Sayers’ friend C.S. Lewis was aware of her success on the radio as a Christian apologist from the late 1930s onwards. When, therefore, in 1941, he was asked by the BBC to broadcast a series of talks on Christianity, he agreed to do so. These talks, together with a further series of broadcasts made in 1942, he would subsequently publish as The Screwtape Letters (1942) and Mere Christianity (1952). Lewis was especially impressed by The Man Born to Be King. After its publication in 1943, he would reread the text each Holy Week, sensing that in this cycle of plays Sayers had produced a work of art that was also an instrument of evangelism.

So, what does the success of a 1940s cycle of radio plays tell us about evangelizing through mass media today?

“Dr. James Welch, the head of religious broadcasting at the BBC at the time, was very clear in commissioning these plays for evangelistic purposes,” explains Wehr. “He wanted to reach the many British people who might never go to church but might now encounter Christ through radio drama.” And, in this regard alone, the plays were indeed a success.

However, the plays may also speak to those working in Catholic media today.

“Sayers felt very strongly that she herself was not an evangelist,” says Wehr. “Her job was to write the best plays she could and then ‘let God do what he likes with the stuff.’ The Creed was her guide: Christ is both God and man. If she could portray that, then she would have done her job.”