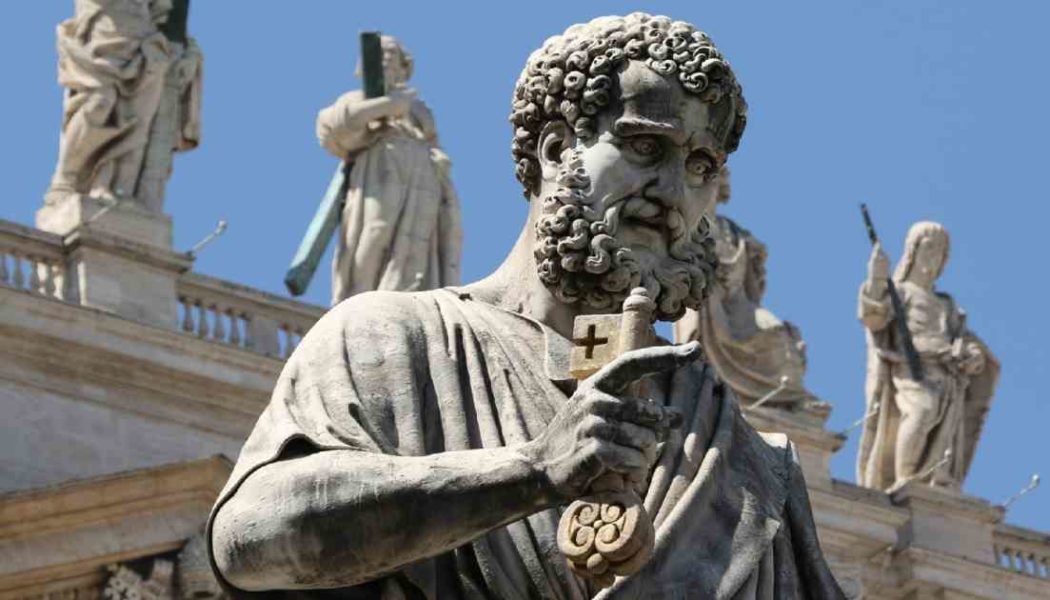

In the Gospel for the 21st Sunday of Ordinary Time (Year A), Jesus gives the keys to the kingdom to Peter. From the very beginning of the Church, Christians understood that this gives Peter incredible authority. We know that too.

But we may have forgotten something just as important: They saw popes martyred regularly; we don’t — and so we tend to forget the enormous sacrifices Jesus asks Christian leaders to make.

Seeing where this passage falls in Matthew’s Gospel is significant, as we shall see.

In the Gospel of Matthew, this moment doesn’t hold the same place as it does in Mark. In classical story-telling, the climax comes at the center of a story — functioning the way the midpoint of a movie does today. Halfway through most movies, everything changes; a false understanding becomes impossible to maintain and a new direction begins: Dorothy and her companions arrive at Oz and find it inhospitable; Luke and his companions arrive where Alderaan should be and find the Death Star instead.

Their understanding of the story they are in changes utterly. In Mark, that is what happens at this moment in the story of Jesus: It is the climactic moment when the Lord finally reveals who he is and what his true mission is — the Passion. But Matthew’s midpoint came two chapters before this story, when John the Baptist was beheaded, then Jesus multiplied the loaves and walked on water.

For Matthew, the death of John the Baptist is the “Aha!” moment when the apostles see that John is not as important as they thought, and when Jesus feeds the 5,000 then tramples the waves they see that he is way more than they thought; in fact, more than human.

This Sunday’s Gospel passage is closely related, but comes two chapter later, as Jesus keeps revealing new truths about the Kingdom he has been talking about all along. The astonishing truth he reveals this time is that Peter will have the leading role in the Kingdom on earth, the Church.

In case we don’t understand what that means, the Church provides us a clarifying reading from Isaiah.

In Sunday’s First Reading, Isaiah shows how Eliakim is made steward ruler of the House of David. Speaking of movies, Robin Hood and Lord of the Rings help us understand the power steward rulers had. In Robin Hood, King Richard’s brother John was weak and wicked, but he still had the power to tax and misuse the people of England. In The Return of the King, Denethor can use his real power recklessly, to the ruin of his family and people.

The two lessons for us: Peter’s steward power is real, and sanctioned by God, but that doesn’t guarantee he will use it well. In fact, Sunday’s First Reading ends by saying that Eliakim’s power will be like a peg fixed to a sure spot. The next lines in Isaiah after our reading ends continue the metaphor by describing how Eliakim’s decisions were so bad, his “peg” broke off.

The Early Church knew exactly what it meant that Jesus named their leader “Peter”, giving him the keys to the kingdom, and saying, “Upon this rock I will build my church and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.”

St. Cyprian of Carthage, who was born a little over 150 years after Jesus, explains:

“A primacy is given to Peter, whereby it is made clear that there is but one Church and one chair. If someone does not hold fast to this unity of Peter, can he imagine that he still holds the faith? If he desert the chair of Peter upon whom the Church was built, can he still be confident that he is in the Church?”

The same understanding of that authority was reiterated at the First Vatican Council in Pastor Aeternus (Eternal Shepherd), the1870 Dogmatic Constitution giving the popes, as St. Peter’s successors, “primacy of jurisdiction over the whole Church of God.” The Council famously added: “When the Roman Pontiff speaks ex cathedra,” from the chair, formally in his teaching office, and “defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church, he possesses, by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, that infallibility which the divine Redeemer willed.”

Nearly 100 years later, the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium (No. 25) added: “religious submission of mind and will must be shown in a special way to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra.”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, in the 1990s, said it this way: “The Pope, Bishop of Rome and Peter’s successor … as pastor of the entire Church has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered” (No. 882).

Wow. That is a lot of authority in the hands of one weak man.

Papal authority may be understandable in cases like St. Gregory the Great or the great St. John Paul II, but is a hard pill to swallow when this same authority is given to some of the weak popes we have seen in the Church’s history — including the fisherman who denied him three times, and made unhelpful demands on the Gentiles, St. Peter.

That is why it is good to keep in mind the limits of papal power. We heard one important qualification in the Second Reading today. St. Paul writes:

“Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How inscrutable are his judgments and how unsearchable his ways! For who has known the mind of the Lord or who has been his counselor? Or who has given the Lord anything that he may be repaid?”

In other words, all of this power that Peter and his successors have really has nothing to do with them. They aren’t wise enough to best the Holy Spirit at wisdom; their advice can never match God’s gift of right judgment; and the Church can live and thrive very well without their personal qualities.

Peter in Sunday’s Gospel is praised for getting Christ’s identity right, when he says, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” — but even here, Jesus stresses that “Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but your heavenly Father.”

Popes remain mortal and the Kingdom remains the Kingdom; Popes are subject to all the demands you and I are in the Kingdom.

Matthew’s Gospel mentions the Kingdom 53 times; 11 more mentions than Luke and three times as many mentions as Mark. Before he tells Peter he will be given the keys to the Kingdom, Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew tells us who the Kingdom belongs to:

- The Kingdom belongs to “The poor in spirit” — never to anyone, including a pope, who is a lover of wealth.

- It also belongs to “Those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake” — never to a lover of fame and honor.

- Those who inherit the Kingdom will be those who “feed the hungry, clothe the naked and give drink to the thirsty” — to those who serve, never to those who act like they exist to be served, pope or not.

And when Jesus talks in Matthew about who is great in the Kingdom,

- … the great aren’t the religious types who cry “Lord, Lord”; but rather “he who does” the least of his commandments “and teaches them.”

- … and the great aren’t the apostles who are argue about who is the greatest; but rather “Whoever humbles himself like a child.”

- Apostles can get to greatness too, of course, but only through bitter suffering.

In fact, many people who think they are a big deal in the Kingdom will discover that they are persona non grata instead. For instance:

- “Many” foreigners from “east and west” will enter while the supposed “sons of the kingdom,” Jesus says, “will be thrown into the outer darkness.”

- A wealthy Pope will find it very hard to enter the Kingdom, since Jesus says “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.”

- And when God’s previously chosen leaders didn’t bear fruit, Jesus said, “the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a nation producing the fruits of it.”

Christ’s promises guarantee authority to the Pope and expect suffering; they don’t guarantee good results.

That’s why this story makes so much sense in the structure of Matthew’s Gospel.

Like I said, this is after the big reveal of who Jesus is in Matthew at the death of John the Baptist, the multiplication of loaves and Christ walking on water. All of the lessons from that turning point can be applied here.

- Peter and his successors have to learn that the great John the Baptist is the paradigm for a Christian leader: The ultimate Christian leader is the one who is beheaded in a dungeon, and the ultimate exercise of the office of Peter is martyrdom, as dozens of the first popes showed.

- The feeding of the 5,000 is an object lesson in what a Christian pope, and every Catholic leader, should be: A servant who feeds the people even when he thinks he has nothing left to give.

- Every pope needs to learn what Peter learned when he walked on water: Never, ever, look away from Christ the judge.

It’s the same for every pope, every bishop, every religious, and ever member of the laity: Believe despite opposition, serve despite your circumstances, and never forget that you will be swallowed up by vicious waves if you follow a path that isn’t with Jesus, for Jesus, and toward Jesus.