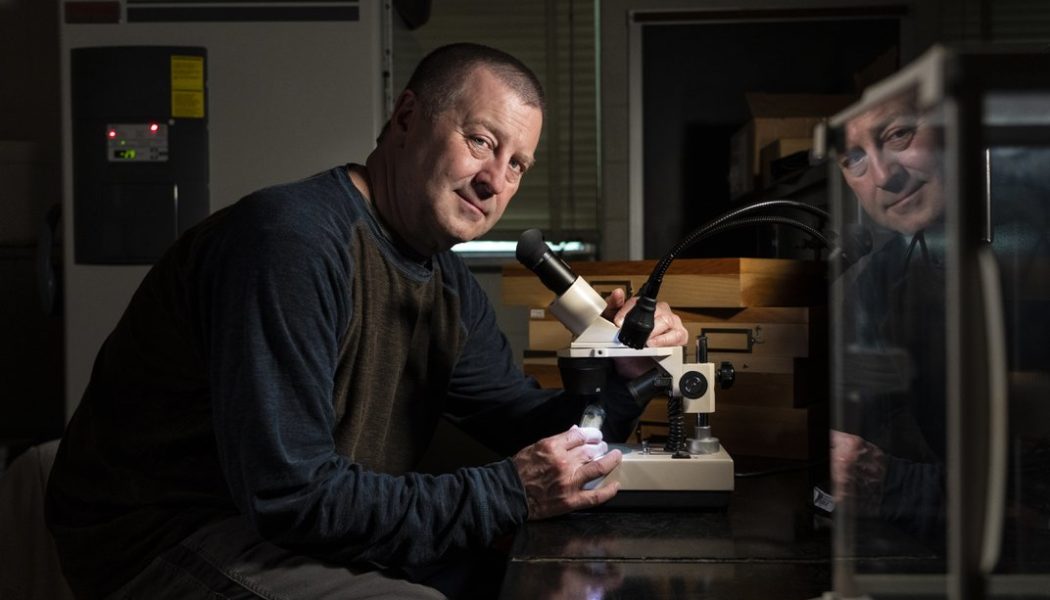

In the dark of a June evening, standing in the black mud of a New Jersey bog, an hour’s drive from home, Christopher Heckscher was alert to any flicker of light. He is an explorer, though this wilderness lies in one of the most densely populated regions of the United States: the Northeast megalopolis. And now, as pale stars appeared from behind the clouds, he needed one more firefly.

Heckscher, a professor at Delaware State University, is an ornithologist who studies thrushes, sparrows and other migrating songbirds. But another fascinating flier captured his attention early on, and he has been publishing papers about fireflies for almost 20 years. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Heckscher was able to focus on his favorite insect close to his home region. He joined with other North American members of an international panel of firefly experts, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission Firefly Specialist Group, to determine which firefly species are closest to extinction, using extinction risk criteria from the IUCN, which maintains a worldwide record of threatened species known as the Red List.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/1e/611e8c4c-e881-4128-8837-cb886ac5a3cb/dsc3484.jpg)

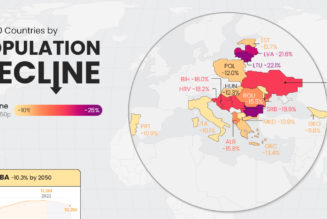

The group concluded that 18 firefly species are threatened, but the major takeaway was that scientists know surprisingly little about the 170 or so named firefly species in the U.S. and Canada. “We had to call over half of the species we assessed ‘data deficient,’” says Candace Fallon, a conservation biologist, who co-led the analysis. “We are still in this information-gathering phase,” Fallon says. “We are still figuring out what species we have in the U.S. and where they occur.”

Heckscher is working to fill that data gap. Colleagues say he’s a rarity. “There just aren’t that many people who are out in the New Jersey wetlands during the right time of night and who are able to distinguish one species of firefly from another,” says Sara Lewis, a professor at Tufts University and a co-chair of the IUCN firefly group. In the world of firefly conservation, Heckscher’s explorations are, she says, “extremely exciting.”

On that June evening, as the sun set, throwing billows of magenta clouds in the western sky, Heckscher saw ferns, grass-like sedges and hummocks of mosses, all signs of a healthy wetland. Wood thrushes dueled with their melodious birdsong across the bog, sounding like an entire bird choir. A great blue heron flew over, its enormous wings silhouetted against the sky’s last light.

A friend who studies moths had tipped Heckscher off to this pristine bog. Bogs are wetlands that depend on rainwater and accumulate hundreds of years of moss in their acidic waters, turning them into giant, sour sponges. As darkness fell, a whippoorwill called—the presence of this declining bird species testifying that this little slice of nature just beyond the New Jersey suburbs was still functioning as it had for eons.

Heckscher expected fireflies to appear in the deepening shadows a few minutes after sunset.

Twenty-five years ago, Heckscher was a wildlife biologist with the State of Delaware’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, managing the state’s rarest species. One project had him searching for the Bethany Beach firefly, which hadn’t been seen since 1968. Was the firefly extinct, falling to one or all of the hazards threatening fireflies throughout the world, such as habitat loss, light pollution and climate change? Or had it simply gone unnoticed for 30 years? The scientific species description gave few hints, only that it had been found in Bethany Beach, Delaware. Frank Alexander McDermott, a researcher who wrote dozens of articles on fireflies, published the first paper about it in 1953. James E. Lloyd, a professor at the University of Florida known as the “Firefly Doc,” had been the last to see it.

Fireflies, known as lightning bugs in the South and Midwest, are neither flies nor bugs. Scientists save the word “bug” for a specific kind of insect with sucking mouthparts—a definition that excludes ants, butterflies and beetles. Fireflies are beetles—magical, but still six-legged insects.

Adult fireflies use their glow as “a love song in light,” as Tennessee-based firefly expert Lynn Faust puts it. A male will flash his signal, and a female will flash a response when she recognizes one of her own species. The females of a few firefly species Heckscher studies can also manipulate their flashes to lure fireflies from other species, which they then eat. In firefly larvae, the glow warns predators of toxic chemical defenses, much as the red of a ladybug or the orange of a monarch butterfly does.

A number of land creatures make light from chemicals, including various fungi, earthworms, millipedes and fungus gnats, Lewis writes. But beetles are the champion, with about 2,500 different species that make light, most of them fireflies. Their glow comes from an abdominal organ called the lantern. Inside that organ, oxygen interacts with a small, energy-packed molecule called luciferin. Some scientists believe fireflies create their pulsating patterns by regulating the flow of air.

There are at least 2,200 firefly species around the globe. Each has a glowing larval (immature) form. These larvae eat snails, slugs and worms, punching way above their weight in the web of life. But not all firefly species have adults that glow. Roughly 60 to 75 percent do, according to Oliver Keller, a biologist with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, who is putting together a checklist of the world’s firefly species. These species are mostly found in Asia and in North America, east of the Rocky Mountains. Fireflies thrive where the air and the ground are moist, and the American West is generally too dry for their taste.

The remaining firefly species are “dark” fireflies. They glow in their juvenile forms, and often as eggs, but not as adults. Instead, these adults find each other through scent-like pheromones, which they detect with elaborate antennae. These fireflies lack the lantern organ that fireflies use to flash. (There are also intermediate species that have both a tiny light organ and elaborate antennae to detect pheromones.) In some other species, the female firefly emits a weak, steady glow but does not fly. She merely crawls to the top of a blade of grass or, perhaps, up a tree trunk.

The adult Bethany Beach firefly Heckscher was searching for both flashed and flew. Although some believed the species was extinct, Heckscher had a hunch that it was hiding in an overlooked wetland. He narrowed the search by studying 50-year-old aerial photographs. Between the sand dunes away from the ocean, fresh water pooled, and grasses and shrubs grew. Heckscher went to one of these wetlands and quickly netted the long-missing firefly. Scientists have since found the species in a handful of these tiny wetlands studding a 27-mile-long ribbon of Atlantic coast in Delaware and Maryland.

It was the first in a string of remarkable discoveries. In 2004, Heckscher found a firefly he couldn’t identify rising from the moss near a river feeding into Delaware Bay. He thought it was just an oddball individual until he found one just like it near a river on the other side of the state in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

He had discovered a new species of firefly. He gave it the scientific name Photuris mysticalampas. (Informally, it’s known as the mystic or mysterious lantern firefly.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/a4/29a4c83f-e5fb-48b2-bf4a-d9009288cb99/dsc3416.jpg)

Heckscher has been searching for elusive fireflies ever since, and finding them inspires awe. Once, he searched for mystic lantern fireflies in a cedar swamp on a hot, humid night. Distant lightning lit the swamp in a pink haze. Trees and ferns flashed suddenly from the darkness, bathed in pink light, studded by the yellow-green glow of fireflies.

Heckscher’s greatest achievement is his method of looking for fireflies: seeking out pristine and unusual wetlands. It was that tactic that brought him to a bog in the Edward G. Bevan Fish and Wildlife Management Area in southern New Jersey in late June.

The genus of fireflies that Heckscher studies, the Photuris, are particularly difficult to identify. Many other types of fireflies can be identified through physical characteristics, but not these, because many of them look alike. To identify these fireflies, he says, he has to pay close attention to their flashing patterns. (The mystic lantern firefly, for instance, generally holds its signal between 0.4 and 0.8 seconds and repeats it every three to seven seconds.)

All around the edges of the bog, fireflies signaled to each other. Some flashed in a steady rhythm before pausing, while others flashed irregularly as they flew, but they were all out of Heckscher’s reach. Keeping an eye on a firefly while running quickly through the dark bog would mean tripping over the humped and twisted vegetation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/54/7a/547a8428-9d55-4cf2-b7c5-3d4a21be0c18/fireflies_kbg0022_kbg_plusnight2.jpg)

Finally, one flew within reach. Heckscher expertly flipped on his headlamp so he could track the firefly between flashes. A Photuris anna blinked in the fine mesh of his net as he scooped it into a collection vial. P. anna is a species Heckscher had introduced to science just a few months before. Named after one of his daughters, and commonly called Anna’s firefly, it crossed his path in a New Jersey bog a lot like this one. The best example of that species is now kept in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History’s entomology collection so other scientists can refer to it.

Each of Heckscher’s specimens presents him with more data. So he turned to the last page of his field notebook to write vital information—including the date, temperature and the firefly’s flash pattern—in handwriting so tiny it could have been written by the firefly itself. He ripped out a piece of paper smaller than a postage stamp. “Slow train,” he jotted to describe the firefly’s flash, a series of blinks. “Freshw. bog,” he noted of the habitat. He dropped the paper into the vial with the firefly.

Soon, Heckscher had a second firefly in a collection vial, another P. anna. A pre-dawn wake-up call for a bird-research expedition loomed closer, but the bog held so much promise that he hated to leave without at least one more firefly. He had hoped to find a brand-new species in this isolated wetland. And a few weeks before, in a twin of this bog just across a sandy access road, he had captured a firefly with a sparkling flash that seemed different from any he had seen before. It was too soon to say it was a new species, and he had already given up seeing another like it on this cool night in June.

Still, he was not disappointed. At home, where he moved his firefly collection after the roof of his university office sprung a leak, he had collected all the specimens he needed of what he believes may be yet another new species. This one gives one blink, while other, similar-looking fireflies give four quick flashes. He won’t declare it to science, however, until he’s compared it with the other species in the Smithsonian’s firefly collection.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/57/4d/574d2a39-2b1e-4834-b6c2-71caa2cefbe8/dsc3687.jpg)

Heckscher had other goals for the evening. At the nearby bog he had captured a Photuris eliza, another of the new species he had just described. This species is also named for one of his daughters. He discovered that firefly in Delaware and had never seen it outside of that state until recently. He wanted more samples from New Jersey to confirm that its range extended there. All night he had seen the irregularly timed, crisp, bright flashes of P. elizas around him, always outside the range of his net.

As Heckscher stood in the dark bog, vehicles grumbled down a nearby road. Passenger jets blinked across the sky. The paved-over world pressed in. As the evening cooled, there were even fewer fireflies to be seen (their flashing slows to a halt as temperatures drop), and none went anywhere near Heckscher. Reluctantly, he hoisted up his backpack and followed the surveyor’s tape he had tied earlier to mark a path through the dense brush to a sandy access road.

Suddenly, he flicked off his headlamp. A firefly glowed near his elbow. Within seconds, it was in a vial. The firefly had been mangled when he found it, so it was hard to figure out exactly what it was, but Heckscher suspected it was Photuris eliza. Later, he would compare it with specimens in his collection of 1,000 fireflies and be satisfied with his hunch.

On the access road, exposed patches of white sand glowed in his headlamp. Heckscher flicked off the light again, took two steps to the edge of the road and plucked a glowing firefly from a shrub with his fingers, dropping it into another vial. It represented the third of the four firefly species Heckscher had recently discovered and scientifically described.

He had named this one Photuris sheckscheri, after his father, Stevens Heckscher, a mathematician and naturalist. He’d first discovered it in a shrubby wetland much like where he found this one. He was once again in the right place at the right time. The fourth firefly species that Heckscher recently described, Photuris sellicki, named after the Canadian explorer Philip Sellick, occurs in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, a significant distance away and a different environment, so he would not encounter it in this coastal bog. He first noticed that species back in 2008. A lot has changed since then.

Heckscher says he’s seen a surge of public interest in fireflies in the last five to ten years. He credits Faust’s field guide Fireflies, Glow-worms and Lightning Bugs. While she wrote the guide for the public, Faust notes that it was peer-reviewed by other firefly experts, just as published scientific research is.

“Now there are firefly tours and festivals,” says Heckscher. “Fireflies are becoming popular, like they should have been a long time ago.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/44/b9/44b9ebc2-79dc-4fe4-9a08-76ce86ffa898/dsc4031_kbg.jpg)

Scientists and conservationists welcome the public’s participation. “Everyone can play a role,” says Fallon. “Whether it’s protecting habitat, assisting with research through community science programs, students deciding to research fireflies or getting folks excited about identification, there are a lot of different ways this can play out.”

What hasn’t changed since Heckscher began his explorations is some fireflies’ dependence on rare habitats. The Xerces Society and another wildlife conservation organization, the Center for Biological Diversity, filed a petition with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2019 for an emergency listing under the federal Endangered Species Act for the Bethany Beach firefly, the species Heckscher rediscovered back in 1998. Fallon expects a ruling in 2024.

The petition noted that houses are being built on one of the last between-dune wetlands with an abundance of Bethany Beach fireflies. The species, found only in Delaware and Maryland, is already listed as endangered in Delaware. It’s the first firefly to be considered for a federal endangered listing. In March 2023, the Xerces Society also filed a petition to list Photuris mysticalampas as an endangered species.

“If you’re going to value the diversity of life on earth,” Lewis says, “it’s not just valuing lions or tigers or bears. Fireflies are, of course, dazzling beetles, but they’re also kind of a gateway bug for raising awareness about the need to conserve biodiversity and particularly the importance of insects.”

That’s what keeps Heckscher in swamps and bogs at night. “Any time I get even two firefly species out of a bog in New Jersey, I’m pretty happy,” he says. “What’s amazing to me is that this single bog had three species of fireflies that, before my paper was published, were undescribed.”

With the new data these specimens represent, the firefly explorer added a few more glowing dots to the map of biodiversity, helping to chart a future for these brilliant beetles. “When you add rare insects to rare habitat types, it creates an important conservation target,” Heckscher says. That’s what he’s exploring. “I’m not getting a lot of sleep these days, but I wouldn’t want to give it up. I couldn’t give it up. I love the challenge.”

Recommended Videos