Several years ago, while doing some investigative reporting on the history of the feminist movement for my book Subverted, I traveled from California to the U.S. Library of Congress to read the Harry A. Blackmun Papers. During previous research, I’d discovered that a little-known book titled Abortion — containing many historical, social, legal and theological errors — had been used as a foundation upon which to build the arguments in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton opinions, which legalized abortion in every state at any time during a woman’s pregnancy.

For our democracy to function effectively, Americans count on the Supreme Court to construct its legal opinions on only the most solid, reliable sources. So how could the Court have cited this decidedly unreliable book seven times as a source for the most controversial decision of the 20th century?

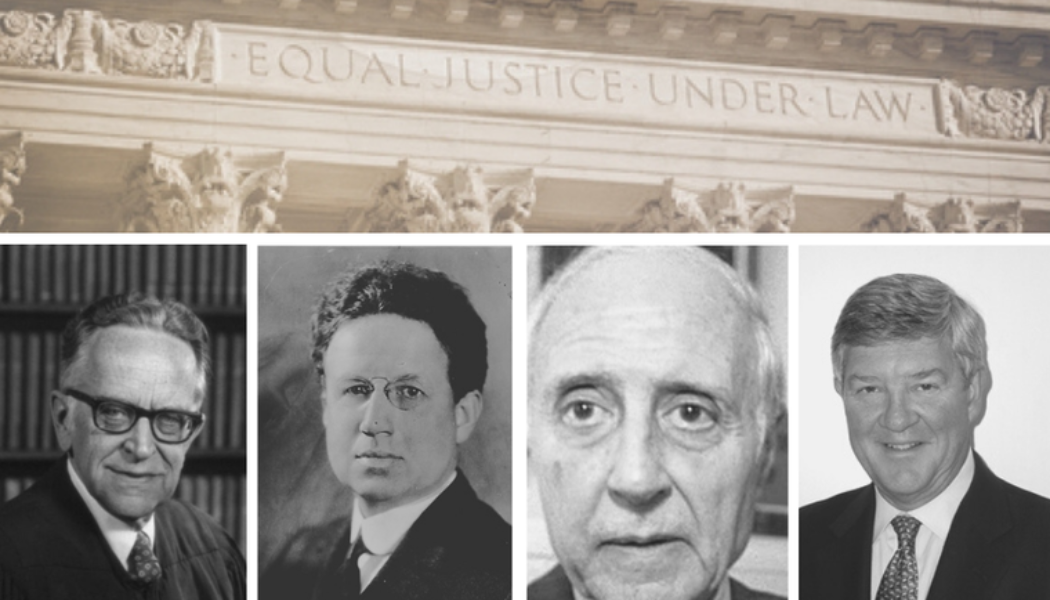

Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of Roe and Doe, had seemingly kept every scrap of paper that ever crossed his desk — 500,000 pages in all, which (along with 38 hours of oral history) now sit in some 1,600 boxes on more than 600 feet of shelf space in the Library of Congress. So it seemed the Blackmun Papers might contain clues to help unravel the mystery.

The abortion debate in our nation is typically framed as a culture war pitting “liberal Democrats” against “conservative Republicans.” This intensely polarizing issue has affected all three branches of government on federal, state and local levels. So how did Harry Blackmun, by all reports a good family man, professed Christian and conservative Republican, wind up writing the Roe and Doe opinions that legalized abortion in every state?

To put it mildly, it wasn’t easy. A Richard Nixon appointee and conservative Republican confirmed by the U.S. Senate in a 94-0 vote, Blackmun had grown up in a working class neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota, the son of a father who struggled to make ends meet by wholesaling fruits and vegetables. Talented as an orator, Blackmun won a scholarship to Harvard at age 16, but separating from home for him had been tough. The night before he left for his sophomore year at Harvard, both he and his mother Theo wept, and he wrote in his diary that “parting with the best home folks available and with one’s greatest pals in the world, was one darn hard job.” At age 61, when he arrived on the Court, Blackmun was by all accounts a devoted husband and family man who attended the United Methodist Church, tithed regularly and even gave an occasional sermon.

Shortly after Blackmun arrived on the court, the assignment was handed to him as an unwelcome surprise. Chief Justice Warren Burger (a childhood friend of his) assigned him the task of writing the opinions — even though, according to former Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, Blackmun’s craftsmanship lacked finesse and he was “by far the slowest writer on the Court.” Not only had the justices’ votes in the closed-door conference after oral arguments been too close to call, but the Chief believed the Court’s final decision would stand or fall on the writing of Blackmun’s opinions.

Unfortunately for Blackmun, abortion was a subject he’d rarely thought about. One evening in 1972, shortly after he’d been assigned to write the abortion opinions, Blackmun was having dinner at home with his wife Dottie and their three grown daughters. He asked the four women sitting around the table, “What are your views on abortion?” New York Times journalist Linda Greenhouse reports that his daughter Susan, the youngest, recalled: “Mom’s answer was slightly to the right of center. She promoted choice but with some restrictions. Sally’s reply was carefully thought out and middle of the road. … Nancy, a Radcliffe and Harvard graduate, sounded off with an intellectually leftist opinion. I had not yet emerged from my hippie phase and spouted a far-to-the-left, shake-up-the-old-man response. Dad put down his fork mid-bite and pushed back his chair. ‘I think I’ll go lie down,’ he said, ‘I’m getting a headache.’”

Still, when facing a difficult task, Blackmun was no slacker. Given a tough job to do, he was determined to do it right. To write his opinions, he retired to the justices’ second-floor library, where he spent most of his waking hours in silent solitude, laboriously working at a long mahogany desk. Months passed. As the winter snows melted into spring and the cherry blossoms burst into bloom, Blackmun remained squirreled away in the library.

When in mid-May, Blackmun at last showed a draft of his Roe opinion to one of his politically leftist, $15,000-a-year law clerks, the clerk claimed to be “astonished” the draft was so crudely written and poorly organized, according to the Blackmun Papers. To make a long story short, Blackmun got flak from his colleagues on the bench, both from the left and the right. So he withdrew the draft, asking that all copies be returned to him. Feeling the oral arguments for the cases had been weak, he had already been planning to visit the Mayo Clinic Medical Library in St. Paul, Minnesota, to do his own research on abortion. The Mayo Clinic was a special place for Blackmun, according to Greenhouse’s book; he had spent what he would later recall as the nine happiest years of his professional life there as a “doctors’ attorney.”

According to The Brethren, while he was researching abortion at Mayo in the summer of 1972, one of his politically liberal law clerks — 28-year-old George Frampton — stayed behind in Washington to help write the opinions. In contrast to Blackmun, George (a former managing editor of Harvard Law Review) was an excellent writer. It’s clear from the written record that George helped Blackmun structure the opinions and wrote much of the abortion history in Roe and Doe.

What’s more, Blackmun and his clerk constructed Roe and Doe largely upon the false assumptions found in that unreliable book previously mentioned. Published in 1966, the book’s full title was Abortion: The first authoritative and documented report on the laws and practices governing abortion in the U.S. and around the world and how — for the sake of women everywhere — they can and must be reformed. Its author was a magazine writer named Lawrence Lader, whose most significant previous work had been a biography of Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger (whom he proclaimed to be “the greatest influence” in his life).

Co-founder with Dr. Bernard Nathanson of the National Association to Repeal Abortion Laws (now NARAL Pro-Choice America), Lader was an heir of old money who believed the world was becoming so overpopulated with poor people that we would all soon starve to death, a premise he laid out in another of his books, Breeding Ourselves to Death. In his view, the way to stop all those poor women from overbreeding and ruining the planet was to get them on contraception, with abortion as a backup when contraception failed.

A sexual revolutionary, Lader wrote in Abortion II: Making the Revolution that the idea of legalizing abortion “struck at the tenets of the Roman Catholic Church and fundamentalist faiths, but even more important, at the whole system of sexual morality to which the middle class gave lip service.” Calling pregnancy “the ultimate punishment of sex,” he said that to tamper with abortion meant the whole system of sexual morality in the U.S. could come tumbling down.

Lader had written his Abortion book to craft an argument that would repeal abortion laws in every state — and, amazing as it sounds, he succeeded. His fabricated abortion history, along with two error-ridden abortion history papers by NARAL attorney Cyril Means, provided the underlying structure for Roe v. Wade and are explicitly cited in the opinion 14 times.

One of Lader’s most persuasive arguments was based on the assumption that abortion on demand was “the ultimate freedom” for women — a “right” women had always wanted and which, due to the miracles to modern medicine, was now safer than pregnancy. Ironically, Sanger would eventually split with Lader over his radical ideas about abortion; she frequently and repeatedly condemned abortion as murder. And yet as late as August 1992, According to his papers, Blackmun was still echoing Lader’s claim that women “need” abortion to be “free” when he said Roe and Doe “are, I believe, a watershed on the road we must travel toward the emancipation of women.”

What Blackmun apparently didn’t know was that most of the early feminists who won for women the right to vote opposed abortion, and up until 1967 the call to reform America’s abortion laws was led primarily by men. In his 1,283-page volume Dispelling the Myths of Abortion History, retired Villanova University law professor Joseph Dellapenna writes, “Despite the growing mythology that describes the entire birth-control movement, as well as the abortion reform movement, throughout the twentieth century as a ‘woman’s movement,’ both movements were largely led by men (especially doctors) until the late 1960s.” Further, Dellapenna observes that “until quite recently most feminists were strong opponents of abortion, and the farther back one goes in time the more nearly unanimous feminists become in their hostility to abortion.”

So why, Dellapenna asks, have so many pro-abortion historians (including Lader and Means) seemed “incapable of realizing that until recently even the most militant feminists considered abortion an abominable crime against nature and against women, a crime that society should prohibit and attempt to stamp out”? He concludes that historical revisionists have crafted a new history of abortion “for which there is no evidence except the historian’s intuition.” So that was certainly one false assumption in Lader’s book that led Blackmun and his clerk astray.

But perhaps Lader’s even more persuasive argument had to do with religion — and particularly with the history of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of intentionally killing a baby in the womb. By cherry-picking his way through the history of the Church, Lader concocted a history in which he claimed the Church had been confused for two millennia about where to draw the line about abortion and when life begins. Weaving an intricate web of words in which he included a medieval debate among theologians over when a baby’s body was “ensouled,” Lader divided the baby’s soul from the body, thereby implying that until a “fetus” is “infused” with a soul, the baby in the womb is not a real person even in the eyes of the Church.

What Blackmun didn’t know is what the Catholic Church has taught since apostolic times: that a living human person is not separated into two parts (physical/spiritual), but is one unified embodied soul. As David Albert Jones, director of Oxford’s Anscombe Bioethics Centre, observes in The Soul of the Embryo, even during those historic periods when the “ensoulment” debate was going on, “the deliberate destruction of [the embryo] was regarded as a form of homicide.” Christ, the timeless Son of God, entered into time in the flesh as an embryo.

When Lader verbally sliced and diced the baby in the womb into pieces — the material body split off from the soul — he was simply echoing an old Gnostic heresy that has plagued the Catholic Church since the first century. Gnosticism, which teaches that a “gulf” exists between God and the material world, is a shape-shifter. It can take many shapes depending on whatever ideas are currently in vogue.

Why was Blackmun, who wrote of the “ensoulment” notion in his opinion, so vulnerable to the theological errors Lader promulgated? Although we can’t read Blackmun’s heart, we can know from reading his papers that he was quite fond of the theories of liberal Protestant minister Harry Emerson Fosdick.

A key figure in the liberal-fundamentalist split in American Protestantism in the 1920s, Fosdick was a rationalist who refused his entire adult life to recite the Nicene or Apostles’ Creed. He rejected many apostolic Christian teachings, including Jesus’ virgin birth, his bodily resurrection and the second coming (which he called an “outmoded phrasing of hope”). Preaching “deeds, not creeds,” Fosdick taught that one becomes a “real person” through action. Characterizing a baby as unfinished at birth, he wrote, “The basic fact concerning human beings is that every normal infant possesses [only] the rudiments of personal life.”

One of Fosdick’s many critics, New Testament scholar J. Gresham Machen, declared, “The question is not whether Mr. Fosdick is winning men, but whether the thing to which he is winning them is Christianity.”

Firing back at his critics, Fosdick countered, “They call me a heretic. Well, I am a heretic if conventional orthodoxy is the standard. I should be ashamed to live in this generation and not be a heretic.”

Still, millions of Americans (including Blackmun) thought Fosdick was just marvelous. This was an easy-to-understand, human-centered “gospel” without all that confusing mystagogical stuff in it. Industrialist, philanthropist and population controller John D. Rockefeller Jr. was so drawn to Fosdick’s version of “Christianity” that he funded the nondenominational Riverside Church in Manhattan (complete with a school, gym, dance hall and 22-story bell tower), where Fosdick became the first pastor and preached for 16 years.

Greatly impressed by Fosdick, Blackmun fondly recalled Christmas Eve 1930 when he, as a 22-year-old college student, was introduced to the famous preacher at a friend’s house and they shared an “instructive” evening together. At age 78, in a talk he gave on Sept. 20, 1987, from the pulpit of the Metropolitan Memorial United Methodist Church in Washington, D.C., Blackmun recalled:

Dr. Fosdick then was the senior minister at Riverside Church and at the peak of his national reputation. … After dinner, he asked if we would like to go over to the church and climb the bell tower to see the city from that height. We agreed. He led my roommate and me up those long stairs into the cold of a December night in New York. We finally reached the level of the bells and looked out upon what seemed to be a great mass of lights. Lights of the Bronx and up the Hudson, lights across the East River to Queens and Brooklyn and Long Island, lights west across the Hudson into New Jersey, and lights south over Manhattan itself. I exclaimed about its beauty and how special it was to be there on Christmas Eve. Dr. Fosdick turned to me and said: ‘Young man, it is beautiful, but under that apparent beauty and under those lights there is more misery than you can imagine.’ I have never forgotten. … The struggle against the imperfect has never been won. … ‘The question … is what are you going to do about it?’ That, I think is the challenge — the Christian challenge if you will — for these times.

According to Fosdick’s version of Christianity, the world is imperfect and unfair, and it’s entirely up to the courageous, powerful, self-made man of action to fix it. Blackmun seemed to envision himself to be such a man. We’re often told a public servant must not allow his personal relationship with the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (or his lack thereof) to “impose” itself on others in the public square. But one cannot separate what a man believes from who he is and what he does. Harry Blackmun’s beliefs about God and man very much affected and influenced the writing of Roe v. Wade, a public document that has contributed to the deaths of millions of innocent little people. As journalist Stuart Taylor Jr. observed in Legal Times, Blackmun saw “every abortion case as a new front in a holy war in which he had a highly personal stake.” To deny the reality that our private lives affect the public square is to submit to illusion.

As for the historical errors that entered the Supreme Court’s abortion opinions through the false legal histories constructed by Lader and Means, detailing them all would require a lengthy book. Fortunately, in Dispelling the Myths of Abortion History, Dellapenna has already debunked those errors for us. In his scholarly paper “The Historical Case Against Roe v. Wade,” he further observed that in another court abortion decision, Casey v. Planned Parenthood (1992), “the only point that all nine justices agreed upon … was that the constitutionality of abortion laws turned upon their compatibility with the ‘history and tradition’ of the nation. Unfortunately, the history in Roe was largely wrong, and none of the justices in Casey seemed inclined to reexamine that history in anything more than the most general terms.”

Far from regretting the historical and theological errors he’d foisted off on the Court, Lader was proud of the ideas in his Abortion book, so much so that he wrote two more books, Abortion II: The Making of a Revolution and Ideas Triumphant, in which he bragged about his victory. The day the Supreme Court’s abortion rulings came down — Jan. 22, 1973 — President Lyndon B. Johnson died, so the case got virtually no press coverage that day. But Lader noticed, and he was elated. The next day, he reported, the leaders of the abortion movement celebrated over champagne, as Lader recounts in Ideas Triumphant.

Meanwhile, because the opinions contained so many errors, Roe and Doe quickly ignited an explosive controversy that left poor Blackmun a prime target of scholarly scorn and public abuse.

The whole truth unites people. But “half-truth, limited truth and truth out of context” (which is how French philosopher Jacques Ellul, in Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, said propaganda operates) tends to divide us and tear us apart. The first critiques of the complicated construct of words known as Roe came from the political left.

In a scathing Yale Law Journal article, liberal law professor John Hart Ely (an abortion supporter) wrote that Roe is “a very bad decision. … It is bad because it is bad constitutional law, or rather because it is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be.”

Ely’s critique was soon joined by other influential voices. “One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found,” observed law professor Laurence Tribe in Harvard Law Review. University of St. Thomas law professor Gregory Sisk, one of Roe’s harshest critics, declared in Missouri Law Review, “The general consensus among legal scholars, whatever their view of abortion or of the ultimate result in the case, remains that the Roe opinion is intellectually and legally shoddy.” As pro-life attorneys Dennis J. Horan and Thomas J. Balch pointed out in their essay “Roe v. Wade: No Justification in History, Law, or Logic”: “Virtually every aspect of the historical, sociological, medical, and legal arguments Justice Harry Blackmun used to support the Roe holdings has been subjected to intense scholarly criticism.”

Meanwhile, the public’s reaction to Roe ranged from adoring praise to impassioned outrage. Letters addressed to Blackmun poured into the court by the tens of thousands, and he read nearly all of them, according to Edward Lazarus in his book Closed Chambers: The Rise, Fall and Future of the Modern Supreme Court. Every epithet imaginable was hurled at Blackmun. He was called Hitler, Butcher of Dachau, Pontius Pilate, Herod, a baby killer and a madman. Letter writers declared “your mother should have aborted you” or “I have been praying for your immediate death.” He received death threats and, once, a bullet through his living room window.

Blackmun, who saw himself not as an abortion advocate but simply as a man who’d received a difficult assignment and had done the very best he could to fulfill it, found the experience disorienting. Writing to a Catholic priest who was a personal friend of his, according to Greenhouse’s book Blackmun confessed, “I share your abhorrence for abortion.” Further, speaking of all the angry letters he’d received, he told the director of chaplain services at Rochester Methodist Hospital, “I have never before been so personally abused and castigated.” During his years on the bench, Blackmun changed from being one of the more conservative members of the Court to one of its most liberal — perhaps, one of his clerks suggested, at least partly due to the adulation he received from the left and the scourging he received from the right, as recounted in Dispelling the Myths.

Although Blackmun cared what Americans thought about Roe, over the years he became more thick-skinned and determined to stick by his guns. Hanging over his writing desk in his office at the court was a framed quotation entitled “Duty As Seen By Lincoln,” which, Koh writes, read:

If I were to try to read, much less answer, all the attacks made on me, this shop might as well be closed for any other business. I do the very best I know how — the very best I can; and I mean to keep doing so until the end. If the end brings me out all right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything. If the end brings me out wrong, ten angels swearing I was right would make no difference.

What if Blackmun had known he and his clerk built Roe upon Lader’s historic, legal, social and theological errors — and that many feminists despised abortion as a crime against women? Did he know that Fosdick had invented his own “self as god” religion, abandoning the Bible and the teachings of the apostles? What if he’d known Lader’s “ensoulment” argument (specifically mentioned in Roe), which split the unborn baby’s soul from the body, was historically and theologically inaccurate? If Roe falls, it will not be because one political party lost and the other won, but because the opinion was built upon a foundation of sand.

Although Blackmun never publicly regretted having written Roe and Doe, ambivalence about the opinions appeared to haunt him for the rest of his life. In an interview published in February 1974 in the Washington Post, he prophetically stated the Roe v. Wade ruling would be regarded “as one of the worst mistakes in the court’s history, or one of its great decisions, a turning point,” as Blackmun’s papers tell. Speaking at the National Prayer Breakfast on Jan. 18, 1979, Blackmun quoted Scripture: “I set before you life or death, the blessing or the curse. Choose life, then, so that you and your descendants may live. …” Then he added, “Help us to remember those words. And may we, indeed, choose life.”

When speaking publicly, Blackmun refused to admit any flaws in the opinions. As he neared retirement, he even quipped in a talk at Harvard Law School that he wanted “to hang around and prevent those jokers from overruling Roe,” as Sisk recounted in “The Willful Judgment of Harry Blackmun.”

Yet privately, when speaking behind closed doors at the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies (according to Blackmun’s papers, a place where he felt safe because he assumed no media people were present), Blackmun confessed in 1992, “The insertion of language, insisted upon by a colleague, to the effect that a fetus was not a person has developed as a focus of abuse. … I wish that language had not been present in the final draft.”

Blackmun said more than once that he would carry Roe “to his grave.” And he did. When he died at age 90, nearly every newspaper in the nation mentioned either Roe or the abortion “right” in the headline over his obituary. For a boy who grew up in a working-class neighborhood in St. Paul and went on to become one of the most powerful judges in America, the fact that his memory will be forever linked primarily to this one case is a sad legacy, indeed. In an ironic twist, at his memorial service, held March 9, 1999, at the Metropolitan Memorial United Methodist Church, the congregation sang Blackmun’s favorite piece of music, The Whiffenpoof Song — “We are poor little lambs, who have lost our way.”

One of many surprises in the Blackmun Papers was a touching poem by an anonymous author. It’s unclear whether Blackmun, the Republican, wrote it or whether it was simply a favorite of his. The poem was tapped out on an old 20th-century manual typewriter and titled The Dawning:

I pray as prayed the contrite thief

To Him who died on Calvary,

‘When thou dost to thy kingdom come,

In mercy, Lord, remember me.’

We knew not, knew not what we did,

And, truly, Son of God art thou;

For us who slew thee didst thou pray

Forgive, O God, forgive me now.

In some segments of our society, Roe v. Wade has been worshipped for nearly 50 years as if it were a stone deity upon whose feet are etched the words “on this rock stands the emancipation of women.” In truth, the opinion is no such thing. For Roe is merely a paper document constructed of words that were written and rewritten by uninformed men — and, in the light of a new day, can be written again.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity