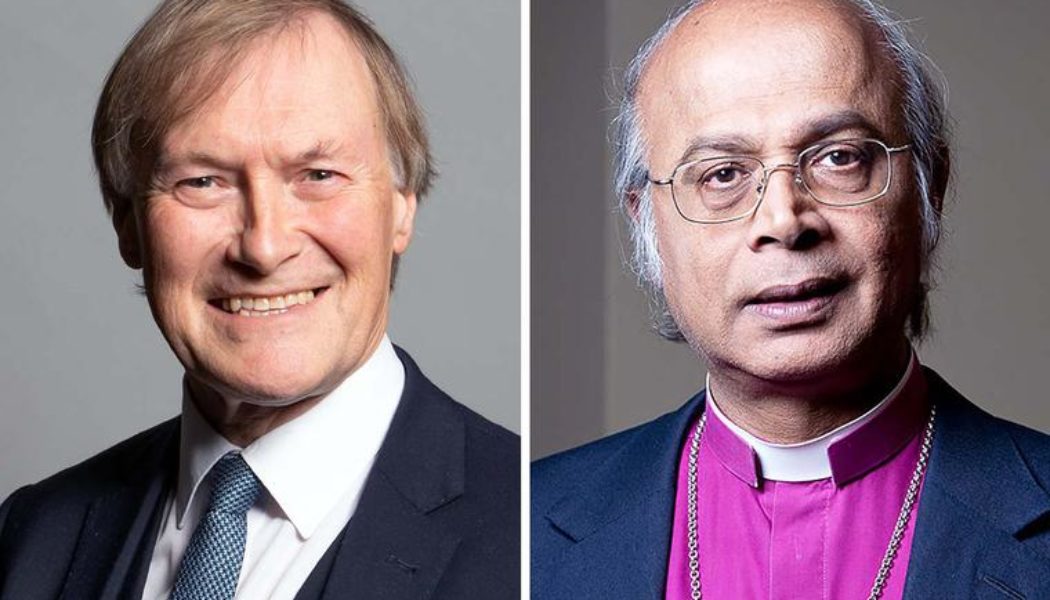

Connecting the dots between the killing of Catholic parliamentarian Sir David Amess and the reception of ex-Anglican bishop Michael Nazir-Ali into the Catholic Church.

“While it is often said that good can come out of someone’s death, it is difficult to see what good can come from this senseless murder.”

So wrote Sir David Amess, the British Member of Parliament stabbed to death while meeting his constituents on Oct. 15. He was not writing about himself, of course, but of the murder of another MP, Jo Cox, in 2016. But the words apply all the more to Sir David who, by universal and multiparty consensus, was the best of the British parliamentary tradition.

A Conservative MP since 1983, Sir David was a staunch Catholic about whom many said, “his Catholicism meant everything to him.” His is survived by his wife Julia and their five children.

“My Catholic faith has sustained me through my period as a Member of Parliament, guiding me in all aspects of my life,” Sir David wrote. “I have been a staunch advocate for animal welfare and a vocal supporter of the pro-life movement.”

The political culture in Britain is different than in the United States, and Sir David was an example of a devout Catholic who devoted his energies to protecting the most vulnerable — the unborn, the poor struggling to heat their homes, animals subject to needless cruelty.

The murder of Sir David was apparently an act of jihadist extremism. The suspect, Ali Harbi Ali, a naturalized Briton from Somalia, has been charged under the Terrorism Act rather than simply for murder, indicating that the police believe an Islamist dimension was at play.

The Islamist killing of a Catholic parliamentarian links the Amess story to another major religious story in Britain, the conversion of the emeritus Anglican Bishop of Rochester, Michael Nazir-Ali, to the Catholic faith.

Nazir-Ali, now a Catholic layman awaiting priestly ordination in a few weeks into the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham — the non-territorial “diocese” set up by Pope Benedict XVI for Anglican converts — was one of the most prominent bishops in the Church of England.

Born and raised in Pakistan, he served as bishop of Rochester — the former diocese held by the martyr St. John Fisher in the early 1500s. In the 1990s Nazir-Ali emerged as one of the Church of England’s most theologically sophisticated and publicly compelling voices. That he was a dual Pakistani-British national made his public profile all the more remarkable, given the establishment status of the Church of England.

In 2002, he was one of two names nominated to be archbishop of Canterbury, the worldwide Anglican primate. The post went instead to Rowan Williams.

Nazir-Ali’s conversion is not, by itself, shocking news. He is the 14th Church of England bishop to convert to Catholicism in the last 30 years. Indeed, the “ordinariates” were set up in large part because so many Anglican clergy desired to become Catholic and continue to exercise their pastoral ministry as priests.

The reasons for Nazir-Ali’s conversion are also standard, as it were. He tired of, as he wrote, the Church of England “jumping on every faddish bandwagon about identity politics, and mea culpas about Britain’s imperial past.”

“With my background, I don’t think of myself as a convert,” the former Pakistani Anglican priest and English Anglican bishop says. “Conversion is from one religion to another. I see this more as a fulfillment, that what Anglicanism in its classical form has held more dear is being fulfilled in the progression of the Ordinariate.”

That’s more or less what America’s most famous convert priest, Father Richard John Neuhaus, said on his move from Lutheranism to Catholicism in 1990. Nothing authentically Christian was being left behind; it was a fulfillment of a path already embarked upon long ago.

The connection between Amess and Nazir-Ali? Before Sir David’s murder, the most famous Catholic politician assassinated by jihadi extremism was Shahbaz Bhatti. Indeed, this year marks the 10th anniversary of the murder of Pakistan’s minister for minority affairs.

Unlike Sir David, Bhatti’s death was not unexpected. Offered foreign asylum because of the danger to his life, Bhatti stayed in Pakistan even though he knew that he would be killed. In 2016, Pakistan’s Catholic bishops opened the cause for him to beatified as a martyr.

Nazir-Ali lived inside an Islamic culture from his upbringing in Pakistan. He knew its authentic spirit and the corruptions to which it was prone. Nazir-Ali’s presence was a light from an Islamic country that come to Britain; the alleged murderer Ali was part of the darkness.

Amess and Bhatti were Catholic public servants killed in the line of duty. But Sir David and Dr. Nazir-Ali also shared something in common, a defense of the orthodox Christian patrimony in an England that seems incapable to giving an account for its own Christian heritage. Sometimes that incapacity is most prominent in its established church.

Both Sir David and Dr. Nazir-Ali were considered “traditional” or “conservative” in their respective worlds. They were traditional in their Christian orthodoxy, to be sure, but their creativity makes it hard to describe then as “conservative.” They were faithful in doctrine and innovative in their approach.

Pakistan and England, orthodoxy and extremism — that’s what links England’s two biggest religious stories this week.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity