Hey everybody,

Today is the Feast of St. Brigid, and this is The Tuesday Pillar Post.

St. Brigid was the daughter of a Christian slave; she was born in 451, in a small settlement along the coast of the Irish Sea. Born into slavery, Brigid developed a reputation for holiness as a young child, and at 10 became a servant in the household of her father, a local Irish chieftain.

Brigid annoyed her father because she had a penchant for charity, but the things she gave away to the poor belonged to him, not her. There is a legend which says that her father once tried to sell Brigid to the King of Leinster — but while the men were discussing the sale, Brigid saw a beggar pass by. She picked up her father’s jeweled sword, and gave it to the beggar, encouraging him to sell it for food, to feed his family.

According to the legend, the Leinster king was so impressed by Brigid’s holiness that he convinced her father to set her free. Brigid entered a monastery of women, founded at least two more, and became known across Ireland for her holiness and Christian witness.

She has been venerated as a saint, and the patroness of Ireland, for more than 1,000 years. And here’s something cool: Ireland’s government announced just a few weeks ago that, beginning in 2023, St. Brigid’s Day will be celebrated as an annual public holiday in the republic — the first Irish public holiday named after a woman. Of course, it’s kind of ironic that the government of Ireland sees fit to add a saint’s day to the roster of bank holidays as the country has secularized so dramatically in recent decades. But hey, maybe St. Brigid’s Day will change the narrative.

May St. Brigid, who was born a slave and found freedom in Jesus Christ, pray for us!

The news

— Tapes of prosecutors’ interviews with witnesses in the Vatican financial trial leaked to the Italian media last weekend.

The tapes are absolutely fascinating: A businessman told prosecutors that he worked with the Vatican to spy on Gianluigi Torzi, the broker now charged with embezzlement in the Vatican City’s court. Another witness said Torzi may have tried to get Italian intelligence dossiers on several Vatican officials, by claiming to ‘work for the Holy Father.’ And Monsignor Alberto Perlasca, the prosecution’s star witness, recalled the way Cardinal Angelo Becciu attempted to conceal a 500,000 euro Vatican payment to Cecilia Marogna, the woman indicted as Becciu’s ‘personal spy.’

Things are getting intense — and just strange — in the Vatican trial. Read all about it.

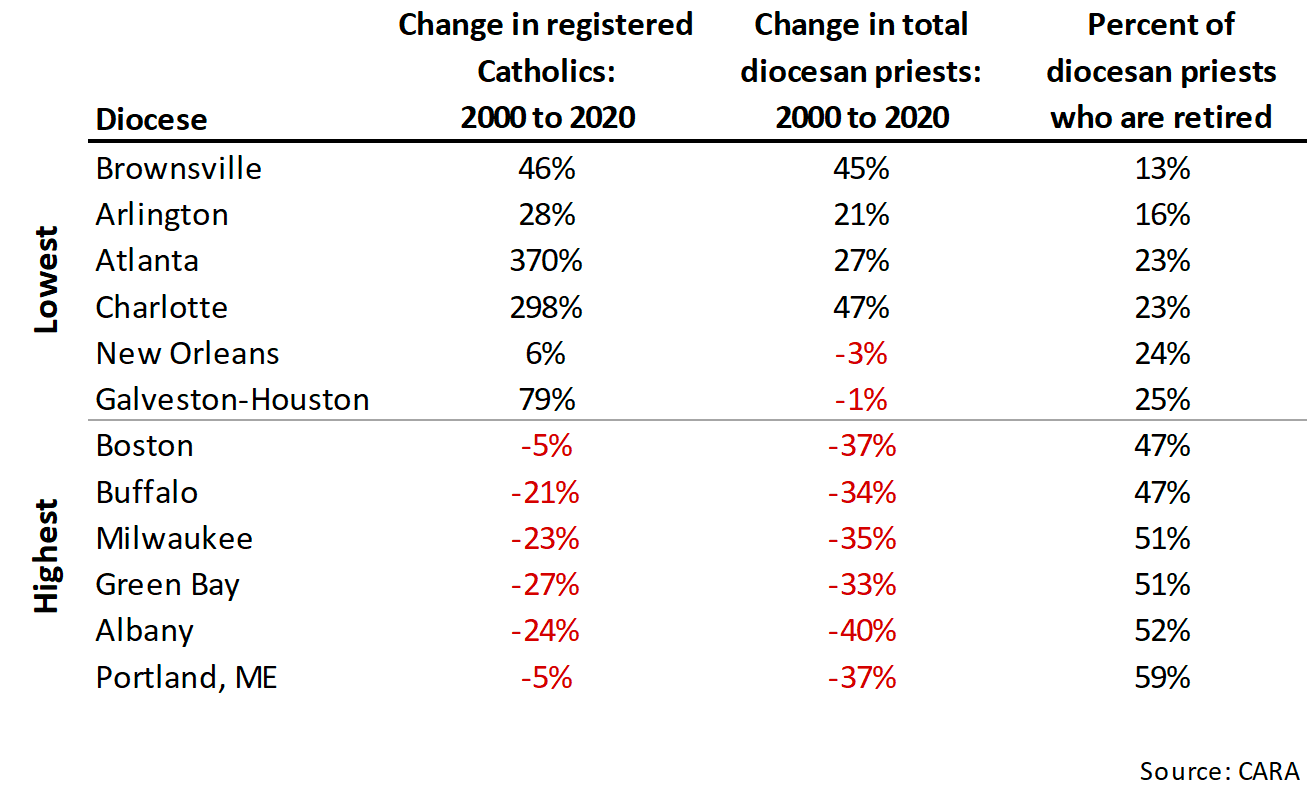

— More than one-third of diocesan priests in the U.S. are retired, and the share of diocesan priests who are retired is expected to keep rising in many parts of the country. The situation can be attributed to a vocations boom in the 1960s, of priests who are now retired or retiring — and to the fact that people, clerics included, are living longer after retirement than they once did.

A glut of retired priests presents some financial and logistical challenges to a diocese, of course. And a look at the ratio of ordinations to retirements across the country can tell us something about the shifting geography and demographics of Catholicism in the U.S.

— A year ago this month, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation said it was investigating an allegation that Bishop John Brungardt of Dodge City, Kansas, had sexually abused a minor.

In an unusual move for a bishop, Brungardt announced he would step away from ministry while both the KBI and a Vatican investigation took place.

One year later, where do things stand? Here’s an update.

— The Sacred Military Order of Malta and the Holy See have reached a kind of fragile peace, after months of tense negotiations, and a dramatic constitutional committee standoff last week. But after much back-and-forth, the order’s leadership and the Vatican have agreed to preliminary revisions to a draft constitution for the order, and to a path forward.

“God has listened to your prayers,” Grand Chancellor Albrecht von Boeselager told senior knights of the order on Friday. Which of the knights, and which of their prayers, we will see.

A few links

— Toward the top of the world, north of mainland Russia and on the way to the North Pole, sits an abandoned Soviet weather station on Kolyuchin Island. And every nine years or so, because of the patterns of sea ice formation in the Chukchi Sea, polar bears take up residence for a season or two, inside the houses of that abandoned weather station. And, really, you’re gonna want to see the pictures.

— Whether you usually agree with Matthew Walther, or you find yourself arguing with every word he writes, he is always worth reading. And this essay, on “the end of the heroic papacy,” is no exception.

For years I have insisted that there is something essentially Wagnerian about this pope. Despite its musical complexity and astonishing run time—around fifteen hours—the theme of the Ring cycle is remarkably simple: the renunciation of heroism, which brings an end to the order of the gods. In their place, mortals find themselves adrift in a homelier but less certain world. In a similar way, it increasingly seems as if Francis’s pontificate has brought us to the end of what I have come to think of as the “heroic papacy,” an understanding of the Petrine office that, from the vantage point of ecclesiastical history, looks every bit as untenable as Valhalla.

— Journalist Will Saletan left his longtime post at Slate this week for a new job at The Bulwark, a publication launched in 2018 by a group of journalists who worked together at The Weekly Standard. Saletan, for his part, wrote a kind of farewell essay last week, reflecting on what he’d learned in 25 years as a writer at Slate.

Saletan is an opinion columnist, and at The Pillar, we try to write our opinions only in these newsletters, and not in news coverage or analysis on the life of the Church. But even though we do different kinds of work, I’m struck by some of the lessons Saletan identified, and especially his growing recognition of his own biases, and unhelpful writing and thinking tendencies, and the way those have played out in his work.

Certainly, I can think of my own, and, like Saletan, I can think of the mistakes they’ve occasioned — some of them stay with you, in a certain way, because they’re the ones you can’t get back.

There’s one I’ve been criticized for recently. Some years ago, I yielded to some internal workplace pressures, and allowed a news report about abuse allegations to include a kind of protracted excursus on grant funding sources for a rival publication’s report. It was cheap, and a distraction from the story that mattered most. It was also out of character for me, and for the irenic, level tone I like to set in news coverage. Criticism of the story, and of me, is understandable — I should have ensured the focus of the story was on the place it belonged, pressure be damned — and I didn’t.

Ed and I left jobs and founded The Pillar in part because we’ve recognized and experienced tendencies in Catholic media that make us uncomfortable, and we wanted distance from the kind of Catholic media tribalism that prioritizes potshots at “rivals,” or that gives excessive deference to figures or institutions on the “right side” of things, whatever that is, in ways that can impede the truth from coming to the fore.

We think ideology is a poison that harms the potential of Catholic media — and since there’s enough of that already, we wanted space to try doing something different.

But to Saletan’s point, we’ll no doubt discover The Pillar’s own unique deficiencies, and the ways we can get better at this, and we’ll do that mostly through the things that didn’t work on first pass.

“If you look back at your work and don’t see any failures, that doesn’t mean you’ve succeeded,” Saletan wrote sagely. “It means you’ve failed to become wiser than you were.”

Still, there is another part of Saletan’s farewell essay that comes as an important warning for those of us who spend time online.

In today’s social media world, he wrote, “I don’t see people learning from, or even recognizing, their mistakes. I see them caricaturing and gloating over the mistakes of others. In the old days, there was a lot of hope that the information age would make us smarter. It didn’t. Instead, high-speed communication, combined with algorithms that discern our biases and feed us what we want, helped us sort ourselves into echo chambers. On Twitter, Facebook, Slack, and other platforms, we’ve formed like-minded battalions that quickly spot the other side’s sins and falsehoods but are largely blind to our own.”

The danger of echo chambers is not only that we don’t hear other perspectives. It’s that they quickly become fora for a kind of performative indignation — a demonstration of our moral superiority which depends on perpetual, biting, sarcastic and escalating outrage.

That kind of thing is endemic to social media, and it serves to reinforce unity among the “like-minded battalions” Saletan mentions. But it deters and prevents the people we disagree with from publicly changing their minds, working through an opinion, “learning from their mistakes,” or offering any show of weakness or humanity — because it stands always at the ready to exploit good-faith communication for the sake of performance. It diminishes the quality of the conversation, prevents mutual enrichment among people of different perspectives, and corrals people into predictable, and boring, idea caucuses. It’s unbecoming of Christians, and it entrenches the tribalistic mentalities that Francis, especially, has cautioned against.

Among people who work at some think tanks and universities, it’s become fashionable, and lucrative, to host symposia on solutions to overcoming the “problem of polarization.” I’m proposing that maybe the solution to that problem is pretty simple: repentance.

The mission of Catholic education

The Church in the U.S. annually observes this week as Catholic Schools Week, in which dioceses, religious institutes, and parishes encourage enrollment in Catholic parochial and high schools.

In light of that week, here’s some of the best reporting on Catholic education published by The Pillar over the past year:

Catholic school enrollment is falling fast: Why some experts see an opportunity

18 months into pandemic, Catholic homeschooling is on the rise

Does Wichita’s ‘stewardship model’ really work?

How a New York Catholic school hopes to transform education for students with disabilities

‘Culture is the hidden curriculum of a school’

Also, in light of Catholic Schools Week, please permit me to advocate, for a moment, for something important to me, and important to the life of the Church: the inclusion of children with intellectual and physical disabilities in Catholic school classrooms.

Longtime readers of The Pillar know this is important to me because two of my own children have intellectual disabilities. But, in truth, it’s also important as a matter of justice, and because of the centrality of people with disabilities to the Church’s credible pro-life witness.

The mandate of the Church’s social doctrine that parishes, especially, should include people with disabilities in all facets of ecclesial life is clear and obvious. Pope Francis, like his predecessors, has emphasized that the Church is to be “a home” for people with disabilities, in a way that our utilitarian and technocratic culture of death rarely is.

And in 1998, the U.S. bishops said directly that “defense of the right to life implies the defense of all other rights which enable the individual with the disability to achieve the fullest measure of personal development of which he or she is capable. These include the right to equal opportunity in education…” — a right which is no less operative within the context of the Church than outside of it.

Of course, federal policy in the U.S. makes special education programs for parish schools extraordinarily expensive — while federal dollars exist in theory to support all students in need of special education services, those dollars are usually administered by public school districts, and almost never make their way into parish schools. Inclusion is sometimes an expensive proposition, and funding is not equitably distributed.

But the U.S. bishops have said that, however much a challenge, funding should not be a deterrent.

“Costs must never be the controlling consideration limiting the welcome offered to those among us with disabilities,” the U.S. bishops wrote to pastors in 1998.

Of course, few bishops in 1998 turned that exhortation into policy, or centralized funding methods, or any other substantive supports for special ed funding in parish schools. And 24 years later, that situation is hardly better — while some dioceses have made laudable efforts to make inclusive special education an attainable reality in parish schools, most have not. The entire issue is seen as being simply out of reach.

The consequence is that pastors are in a difficult position when families like mine come along, expecting to enroll their children in Catholic school, and expecting that the Church’s pro-life commitment will have made that a reality. Pastors, who already stay up at night worrying about their budgets, are asked by families like mine to do a difficult and costly thing, often without curricular, logistical, or financial support from the chancery.

I empathize with those pastors, some of whom are probably Pillar subscribers. They have to balance an ever-shifting constellation of needs, for which they never have enough time, and for which there is never enough money.

But I empathize with them only to a point.

Like a lot of parents of children with disabilities, I appreciate that children like mine can represent an inconvenience, a financial burden, and often require more attention than typically developing children. I appreciate those things because I experience them, in my own day-to-day life, in my marriage, and in my bank account.

But like all parents, I’ve learned that the vocation of love has an immediacy: The existence of the small people in front of me requires that — at times inconvenient and unchosen by me — I must shelve my own plans and priorities in order to meet their practical, visceral, and important needs.

God calls all parents to love like that, whether or not we feel especially qualified, prepared, or well-disposed to the task. That’s just what it means to love in the image of God the Father.

And the Church – by which I mean her hierarchy – has no less responsibility on that front than parents do — because that’s what spiritual fatherhood is about.

It is easy, and common, to put off the prospect of enrolling children with disabilities in parish schools, with “not yet,” or, “someday,” or “we’re just not equipped for that.”

But responses like that, however common, are not a sufficient expression of the Father’s love — not a just response to the immediate spiritual, emotional, social, and intellectual needs of the small souls whom God has entrusted to the Church, which is to be a kind of sacramental conduit of the Father’s love.

I raise these points because children with disabilities rarely have the opportunity to advocate themselves to be welcomed in Catholic schools. But the fact is that parishioners with disabilities belong in Catholic schools as much as all other parishioners do.

Catholic schools have a unique mission – forming children for lifelong discipleship with Jesus Christ. The Church has the obligation to include in that mission the children whose formation happens to demand more time, more effort, and more money.

So pastors, principals, bishops, listen — don’t be intimidated! Don’t be afraid. You can do it!

The pope has said the Church should be “home” for people with disabilities — but that happens only when we decide to make it a reality. So let’s decide. Let’s invite all children to the come to the Lord through the doors of our schools. Let’s begin with “yes,” as the Blessed Virgin Mary did, and trust that the rest will come, through the Lord, as he wills.

And on a practical level, here are some resources. Check out the National Catholic Partnership on Disability, and the FIRE Foundation (I serve on the board of the Denver affiliate.) For even more practical resources, send me a note – I’ll be glad to point you in the right direction.

And if you like, check out this lecture, “Catholic Education and the Importance of Including People with Disabilities“ by Dr. Susan Selner-Wright, a professor of philosophy at Saint John Vianney Seminary in Denver, Colorado.

Happy Catholic Schools Week. Please be assured of prayers, and please pray for us — we need it.

And as a reminder — you’re the best way we can get The Pillar in front of the eyeballs of more readers, which is the kind of thing that helps us continue reporting the news. So if you like The Pillar’s work, don’t forget to send it to other people who might like it too. It helps a lot.

In Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity