In my series on transportation technologies (parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7), we looked at the core principle that drives the lasting life of cities: They are built on communication lines, thanks to which they can trade between their hinterlands and the world. This creates markets, which justify an investment in infrastructure—including new communication lines—which develops the cities and their markets further, and there’s a virtuous cycle where the bigger cities become bigger.

If you enjoyed that series, you will enjoy this new sub-series, where we try to understand how big metropoles reached their status. Earlier this week, I started with Why Pittsburgh Rose and Fell in the premium article

. Today, I’ll cover Chicago. Later, I will share thoughts on California, Texas, New York, Québec, Kansas City, Atlanta, Minneapolis-St Paul, and more.

Here are other premium articles I’ve published recently:

Without further ado, here is…

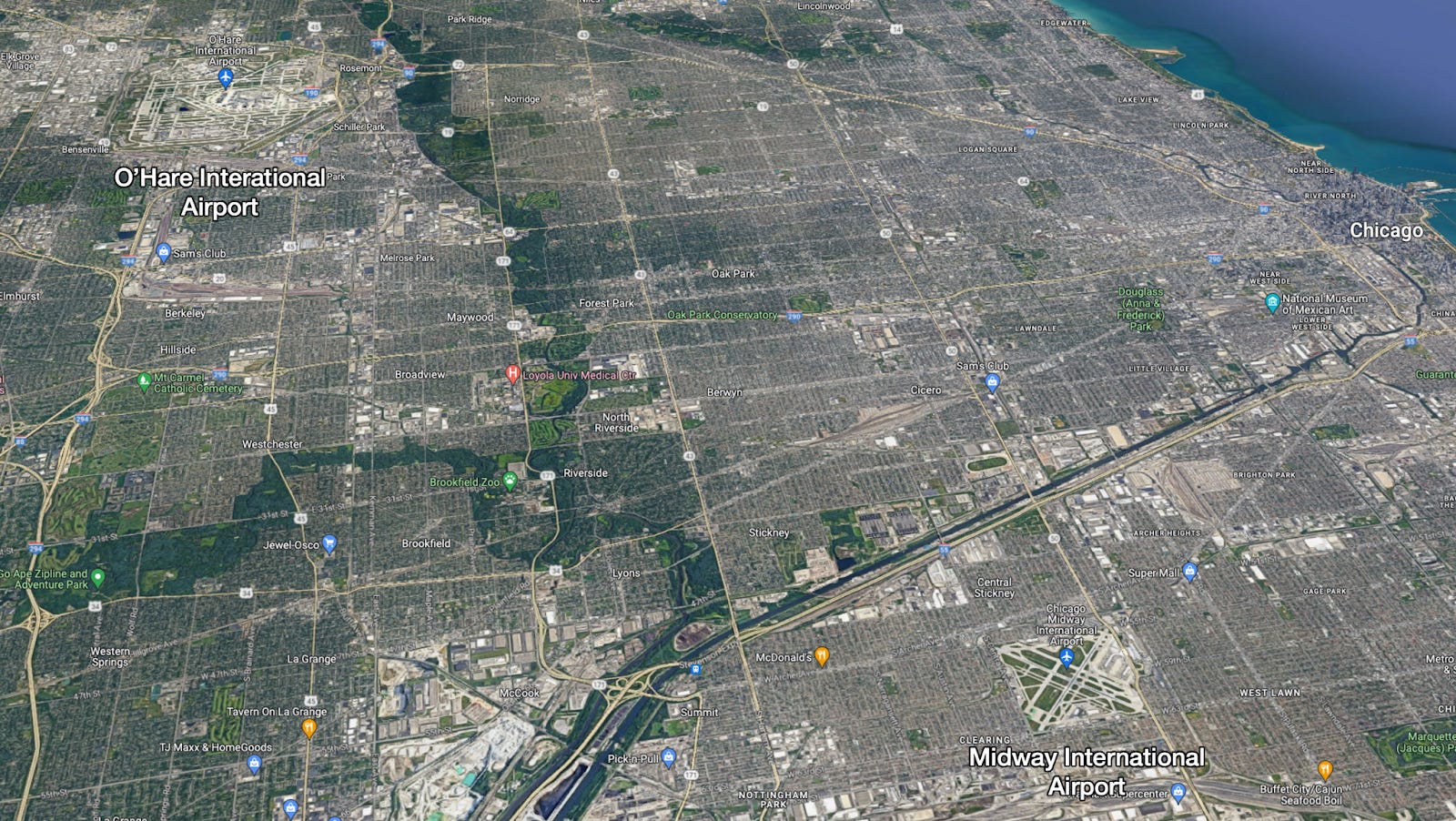

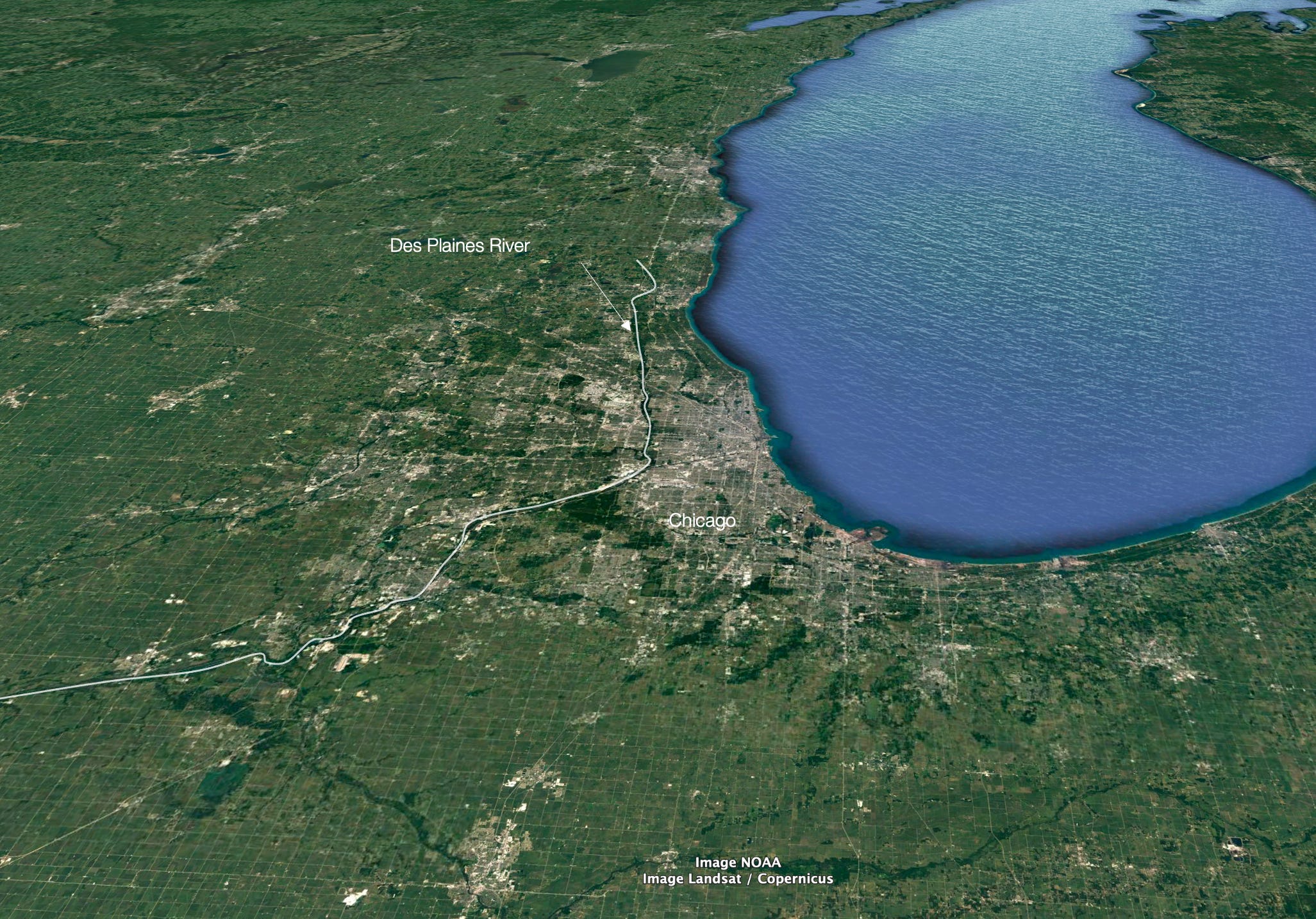

Chicago is the 3rd biggest city in the US, but if you look at a satellite image of the region, you wonder why such a big city is there.

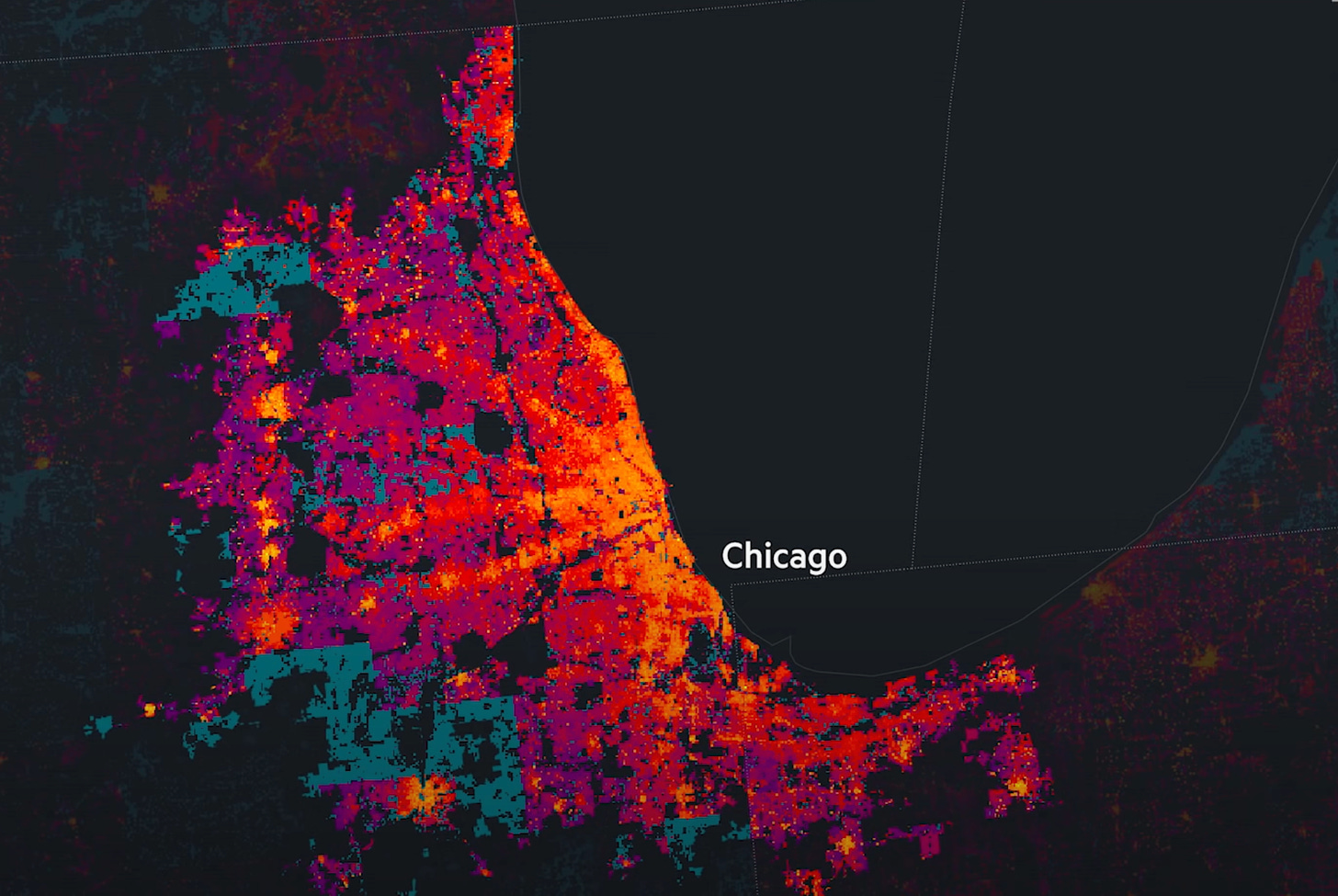

You can tell how big it is by looking at the night lights map.

Why so big? Sure, it’s on the Great Lakes, but aren’t the straits a better place for big cities? That’s where you can best connect land with water, like in Detroit.

Isn’t Chicago a bit far away from all the action?

Yes, but Chicago has something special.

This is the river basin of the Mississippi river. Do you notice something?

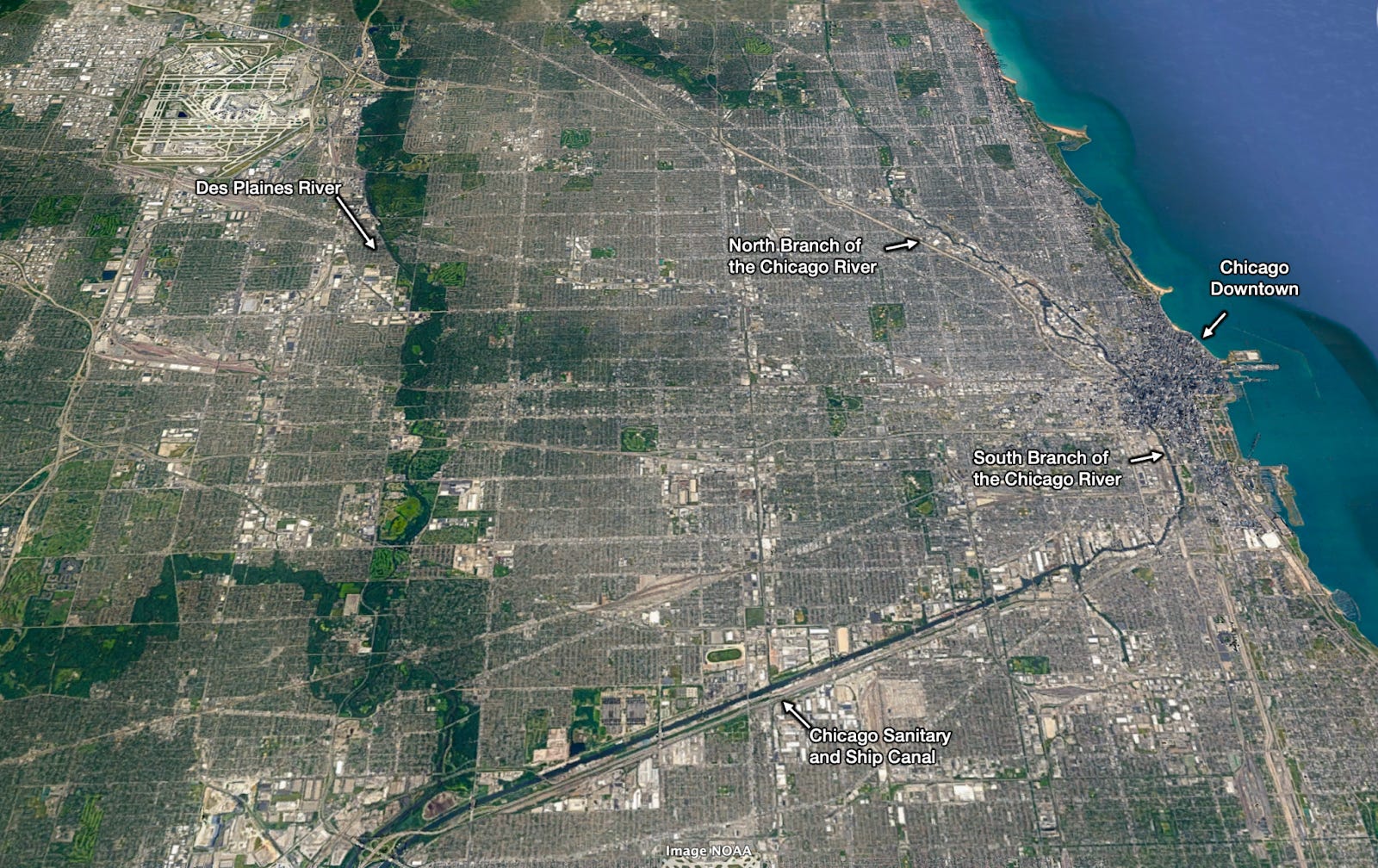

This satellite image of Chicago and Lake Michigan show how close the lake is to the Des Plaines River

, just 6 miles away!

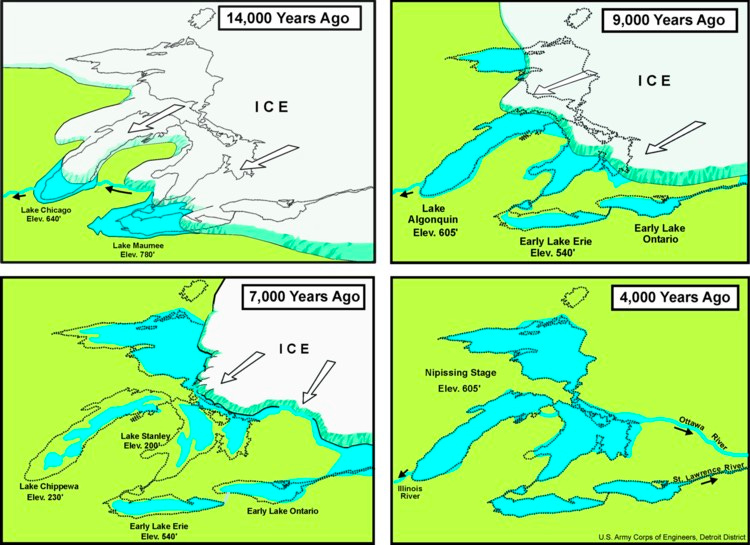

In fact, a few thousands of years ago, water from the Great Lakes did flow through the Mississippi!

It’s only when the water level went down that the flow inverted, just a few thousand years ago.

That ancient river carved out a riverbed, which left a marshy area and a drier area.

When people

wanted to go from the Des Plaines River (and hence the Mississippi River Basin) to Lake Michigan (and hence the Great Lakes), they could use their boats to cross the marshes and then carry them overland.

This type of region is called a portage, and this is the shortest portage between the Mississippi and the Great Lakes areas.

You can see all of this to this day:

-

The Des Plaines River

-

The Chicago River, both North and South Branch

-

How downtown Chicago concentrates around the mouth of the Chicago River

-

The new canal that connects both rivers, and the type of development it has followed in comparison to other parts of Chicago: bigger buildings, oriented towards the canal, likely for warehousing and transportation purposes

This means that out of all the geography of the US, the single best point to connect the Mississippi and the Great Lakes is here, where the Des Plaines River and the South Branch of the Chicago River nearly touch. Given the importance of the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes for transport—and hence the economy—a city was going to be founded here, and it was going to be big.

The American authorities recognized this immediately, and formed a fort here

. But early on, these two rivers weren’t connected. So they organized a trail to ease communication with wagons and roads.

But very soon after, the US built the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which you can see in the satellite picture above.

When the US expelled the natives from Chicago in 1833, the city had just 200 settlers. Seven years later, it already had 6,000. Just eight years after that, it inaugurated the canal connecting the rivers. For several decades, it was the world’s fastest growing city.

And this is why Chicago’s flag has two blue stripes with four stars in the middle: The blue stripes represent the branches of the Chicago River and the canal that connects them to the Mississippi basin, while the four stars represent the city in between.

Between the Great Lakes and the Great Plains, Chicago’s unique position made it the major hub for both. They became the city’s hinterlands.

The upper Midwest and Canada floated their logs of trees down the Great Lakes to Chicago’s sawmills. Chicago became a trade center for lumber.

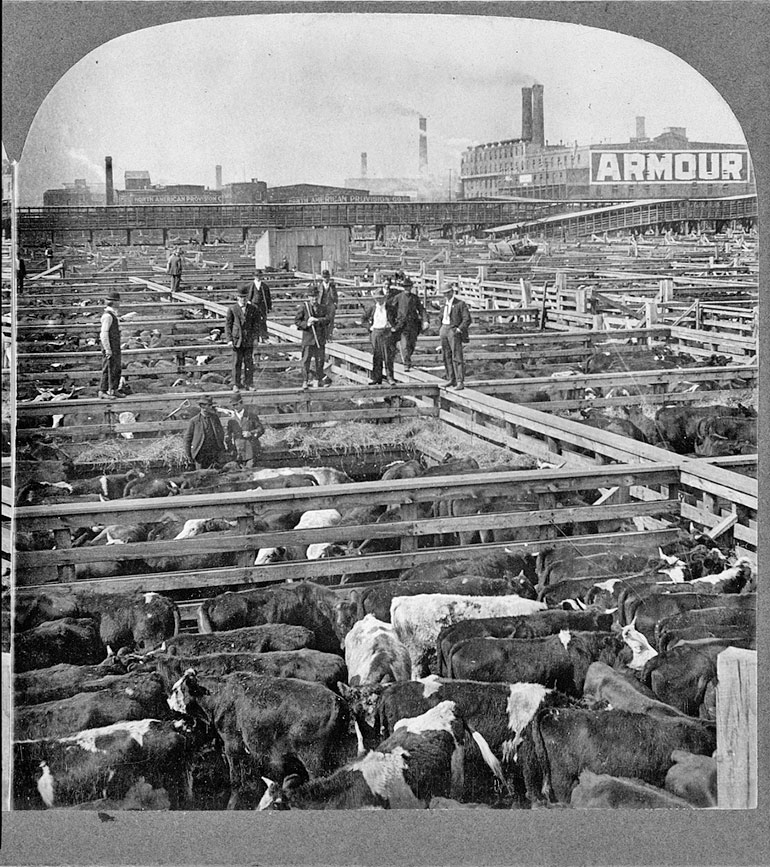

The city also became a center for the meatpacking industry, as cattle from the Great Plains were shipped to Chicago’s stockyards for slaughter and processing.

Over time, grain replaced pastures, and Chicago added grain markets.

In Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, William Cronon argues that Chicago’s success was due to its ability to harness the natural resources of the Great West and turn them into commodities that could be sold to the rest of the country and the world.

It’s good for your economy to connect the two biggest riverine systems, the middle with the east of the country, the north with the south.

But you know what’s even better? Using that to create another level of connections.

In 1848, the same year as Chicago completed the canal connecting the rivers, it also completed its first railroad, connecting it to lead mines. After that, the US entered a frenzy of rail-building. Within a few decades, it had built as many miles of railroad as the rest of the world combined, and Chicago was at the center of that.

Naturally! If you’re already the trading point between Mississippi and the Great Lakes, you have lots of goods, markets, and logistics infrastructure to receive more cargo. So it makes sense to invest more infrastructure into the city.

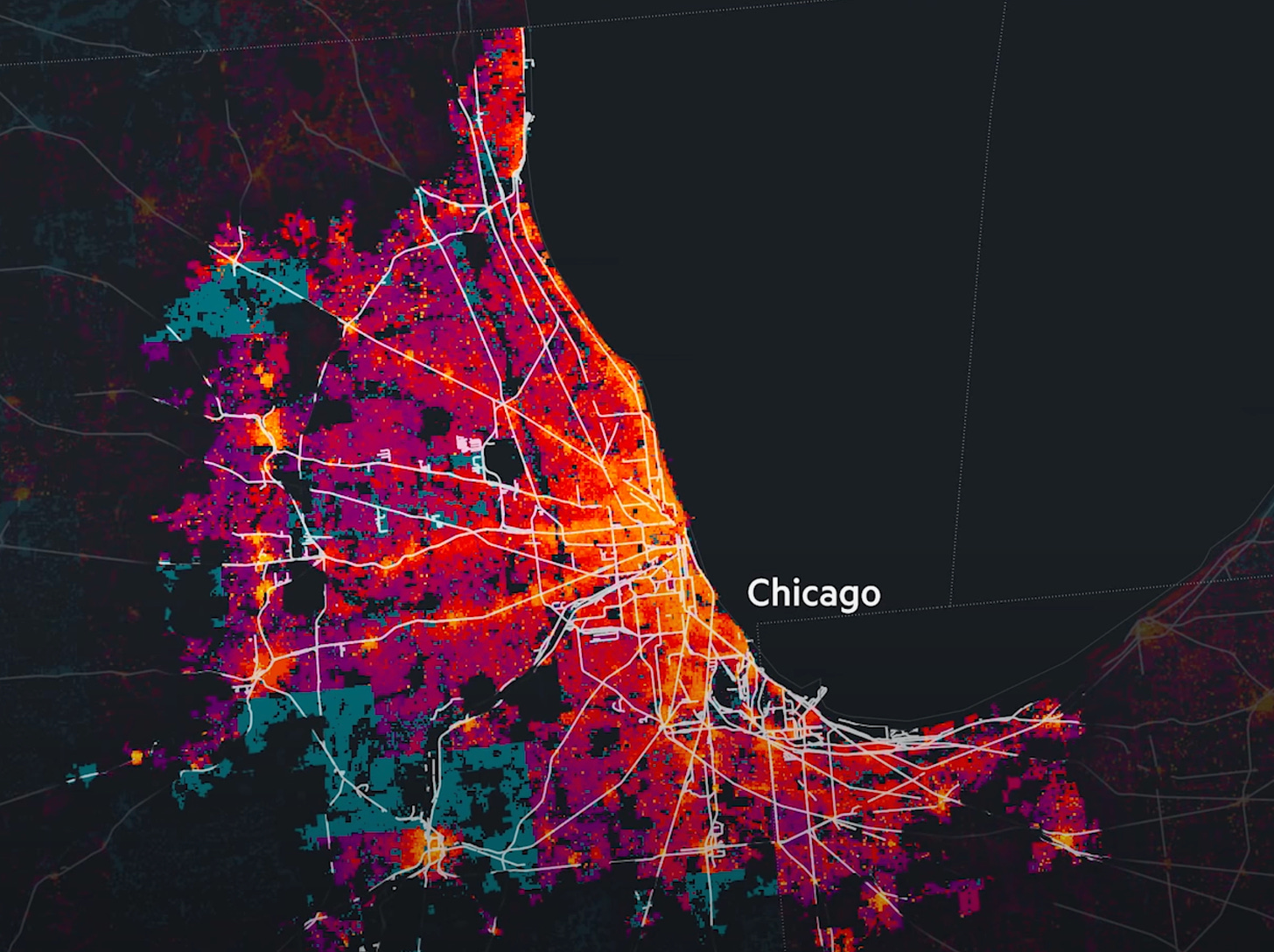

In the map below you can see the time when Chicago was developed: yellow is older, and purple/blue is more recent.

Can you see the yellow lines connecting at the center of Chicago? Yes, these are railroads.

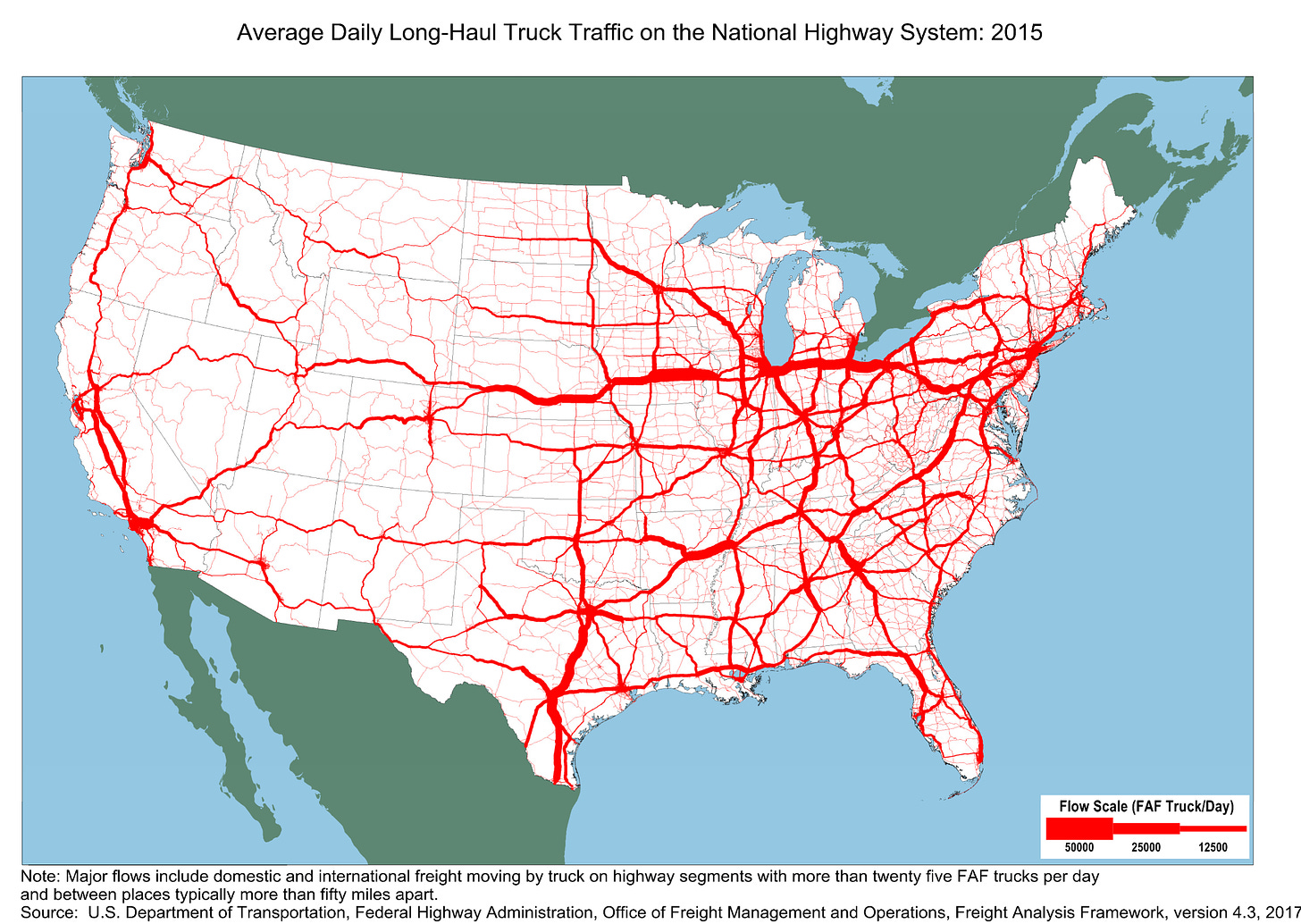

This was true for railroads, but also for roads, and then highways: If you have a truckload of goods in the Midwest, where are you going to go to unload it: Wherever there are more options to ship it anywhere else. If you have a spot in the middle of the country with connections to the two biggest water transportation systems and the best railroad network, you want roads to go to the same place.

And once you have the infrastructure for ships and railroads and roads, you’re even bigger, your market is also bigger. And it makes sense to invest even further in all of it.

In his 1916 ode to Chicago, Carl Sandburg referred to the city as the “hog butcher for the world, tool maker, stacker of wheat; player with railroads and the nation’s freight handle.” With more lines of track radiating in more directions from Chicago than from any other North American city, the description was clearly right on target. The city served as a vital gateway and distribution center for transporting the bountiful grain and livestock from the Midwest to the rest of the continent and the world.—Source.

Today, the biggest commodities market in the world is the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

Originally, it was the Chicago Board of Trade, a grain market created around the 1850s. Later on, it spun off a market for butter and eggs. The details of why this happened are interesting:

During the last half of the 19th century, a fast-growing nation was at the mercy of alternating periods of scarcity and plenty. Cold storage facilities were primitive, markets were disorganized, and major production was seasonal. In the case of butter, for example, a Chicago Product Exchange was formed in 1874 which established grades and rules of trading. Kegs of butter were individually smelled and tasted on the spot, and a price was agreed on. Some butter produced in the warm months was heavily salted and stored in basements for later use. The Chicago Butter and Egg Board was organized in 1898, and by 1915 the Board had developed 28 rules governing butter grading.—History of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

By the 1970s, the Chicago Board Trade and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange processed together nearly 80% of all the commodities transactions in the US.

The bigger your market, the more it has buyers, the more interest you have to go as a seller. The more sellers you have, the more buyers want to join. Network effects.

As trade increased, Chicago kept building up its railways and ports, improving its communications by land and sea.

As time passes, new transportation systems replace older ones. In the case of Chicago, it was first lakes, rivers and canals, then railroads, then roads and highways, and then airports.

Chicago has two airports. O’Hare is the most connected airport in the world and the fourth biggest in terms of passengers, and is the hub for United and American Airlines, and a focus of Spirit Airlines, while Midway is Southwest’s main base. Chicago is still one of the main cities to connect the US East and West coasts.

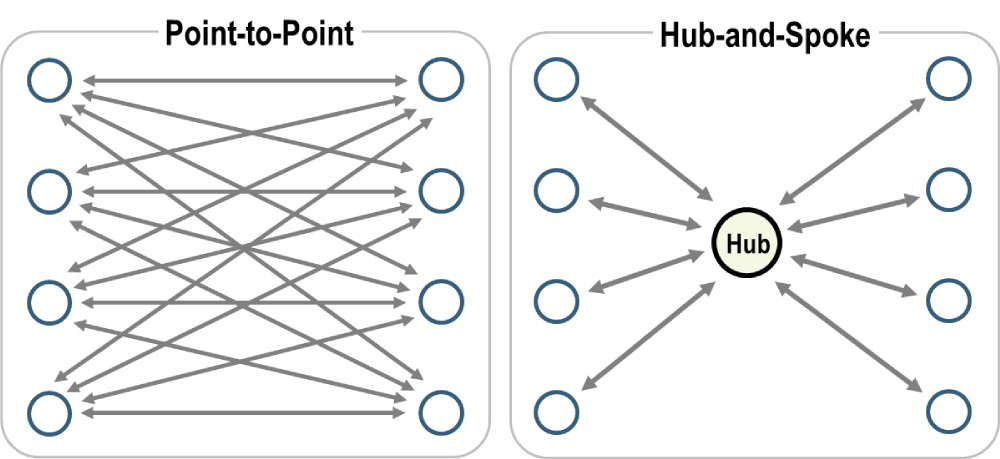

Why is this so valuable? Because of the economics of network effects. Imagine you want to connect four points with four other points. You need 16 connections.

If you create a hub, though, you just need 8.

Not only is it less wasteful, but also this allows each one of these connections to double the number of people traveling in them. The result is that many points that didn’t have enough people to justify a connection before can now justify it with a hub. The result is that hubs concentrate a big share of traffic. The bigger they are, the bigger they become.

The process was true for the Mississippi and the Great Lakes, but with air, it becomes true at a global scale.

As Chicago became a hub for east and west in the US, it got connections with most airports in the country. This is also useful for travelers from other countries: They can reach any US city if they travel to Chicago first. So now Chicago attracts international connections. This allows Americans living in small cities to reach these international destinations by traveling through Chicago, further increasing the number of trips Chicago receives.

All of this creates connections for Chicago to the rest of hubs in the world, which makes trading with them cheaper from Chicago, which attracts further business to the city, and hence wealth and population, further cementing its lead.

Chicago is a the perfect illustration of why some cities develop to become behemoths, and others don’t: network effects.

-

The most blessed cities have an unfair communication advantage. In the case of Chicago, it was at the crossroads of two of the biggest hinterlands in the world, the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Basin. It has network effects between these two.

-

This developed its markets. First meat and lumber, later grain, butter, eggs. More network effects.

-

With strong markets and strong connections, it makes sense to invest further: better ports, better canals. But then also new communication lines: roads, railroads, and later highways. Each time a new communication line is built, it strengthens all the other ones, along with the markets. More network effects.

-

Eventually, Chicago added airports, further reinforcing them.

-

It ended with a mesh of rivers, lakes, canals, roads, railroads, airports, and markets that could hardly be rivaled by any other city around it. It became the local hegemon.