Jesus gives instructions for bishops this Sunday, the Fifteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time, Year B, and thereby reveals the radical call to holiness at the heart of their vocation.

But lest we get the wrong idea, the Church provides two readings that provide important corollaries: One about the humble origins of those he calls to special offices, and the other about the radical call he gives every one of us.

The Holy Spirit makes every word count in the Gospel this week.

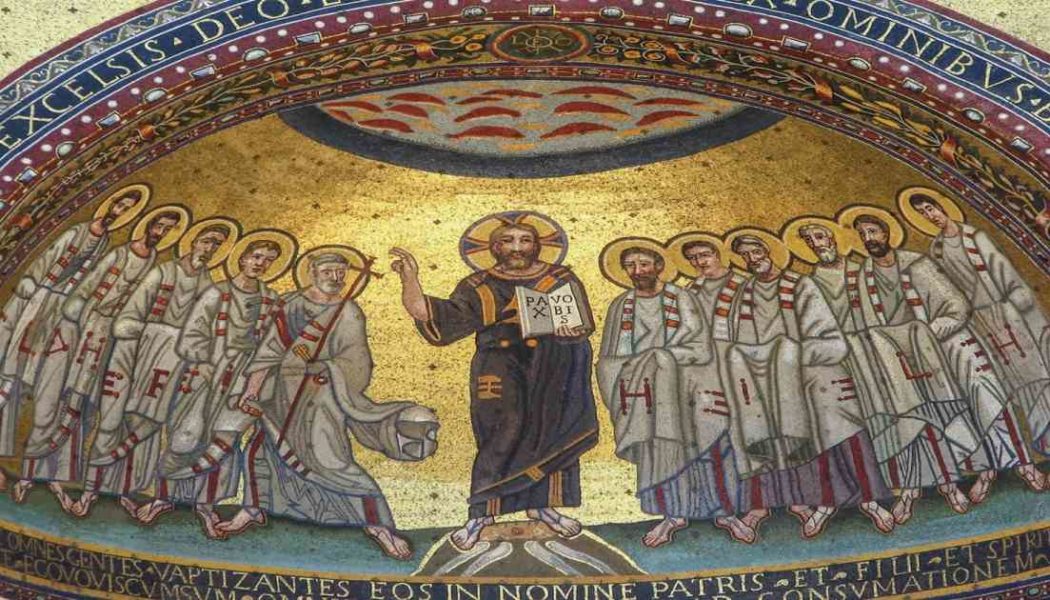

The Gospel begins, “Jesus summoned the Twelve and began to send them out two by two.” Later, in Luke, Jesus will send out the 72, giving missions to laypeople, bishops and priests alike. Here he is summoning the successors of the 12 tribes of Israel, and the first bishops, the first shepherds of his flock.

Jesus “gave them authority over unclean spirits. He instructed them to take nothing for the journey but a walking stick,” says Mark.

Jesus chose them; they don’t choose him. Nothing about this trip is their idea. Their mission comes from him alone, and so does authority. To this day, what bishops do for Christ isn’t their gift to him, it is Christ’s gift to us. Bishops don’t choose to use their talents for Jesus; Jesus decides to make do with their talents. They don’t get personal authority over anything; they get to use Jesus’s authority over “unclean spirits.”

On their own, they are powerless in front of the world, the flesh and the devil. Any power over those things comes from God. Those who follow their own prerogatives follow them to their peril.

The one thing Jesus demands they bring is a staff — translated “walking stick” here. Staffs may be necessary for rough terrain or for older people. They are not strictly necessary for these young men on this journey — but Jesus is training them to be leaders in the Church, and to this day, bishops carry unnecessary staffs, called croziers, as signs of leadership.

Jesus also sends them out by pairs. Jesus delights in stamping the inner life of the Trinity on our lives, and just as the loving cooperation of the Father and the Son generates the Holy Spirit, in the same way, he loves to make one plus one greater than two in his Church. “For where two or three are gathered in my name,” Jesus promises, “there am I in the midst of them.”

He doesn’t see bishops as solitary figures of authority, like dictators. He sees them as collaborators. Matthew even lists them in pairs: Peter and Andrew, James and John, Thomas and Matthew, Philip and Bartholomew, Thomas and Matthew, James and Thaddeus, Simon and Judas.

We see this pairing of disciples from the start of the Church, in Peter and Paul, to today, in Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, or Pope Benedict and Georg Gänswein. We also see bishops’ collaborations with laypeople such as Archbishop Charles Chaput and Fran Maier and the late Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger and Jean Duchesne, and of course in bishops’ collaboration with each other, at councils, synods and assemblies.

Jesus spells out how bishops should act.

First, Jesus specifies what “Take nothing for the journey” means when he says, “no food, no sack, no money in their belts. They were, however, to wear sandals but not a second tunic”

The only things they are to bring are what the mission needs: They need sandals to walk a long way, but extra clothes will just get in the way. They are to rely on nothing but Jesus. Everything about their lives is about Christ, not themselves. It is Jesus who initiates their missions, Jesus who lends their authority, Jesus who uses their gifts for his purposes.

Thus, “Wherever you enter a house, stay there until you leave,” Jesus says, “Whatever place does not welcome you or listen to you, leave there and shake the dust off your feet in testimony against them.”

Jesus is clearly telling the apostles — and their successors, the bishops — that their agenda isn’t to find people they like, people they naturally get along with. Their agenda is to find people who are open to the message of the Kingdom.

A bishop belongs to everybody; or, better, he belongs to Christ’s mission to everybody. A corollary of that is that their mission isn’t to form attachments to people, but to attach people to God. The apostles aren’t to dwell on rejection, or keep obstinately trying to convert people who aren’t interested. They are told to simply move on.

Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t just want them to “shake it off,” like Taylor Swift, when people reject him. He wants them to make a kind of public testimony against them. This is mercy for the people rejecting them and mercy for the apostles. It makes it impossible to “live and let live” but requires them to declare who they are separated from and publicly break from them.

Sometimes, painfully, that will even mean publicly breaking with an apostle, as the Twelve will one day have to do — or with a schismatic bishop, as has often been the case in the Church.

If bishops think they are special, they’re right. But it’s only God that makes their office special; like Amos.

In the first reading, we meet the prophet Amos, who explains that he is no great man. Before he was a prophet, he was a shepherd and a dresser of sycamores. Shepherding was a low-level job, and a dresser of sycamores was lower. Sycamores produced a poor man’s fig. At a certain stage in their development, sycamore figs needed to be punctured to make them grow bigger. So Amos’ job was to walk the sycamores and puncture each of the fruit.

From these humble beginnings Amos became a prophet so effective that King Amaziah of Judah finds him a nuisance and exiles him.

Amos’s two jobs are themselves symbolic of the life of a bishop. He was a shepherd, and bishops hold shepherds’ walking sticks to prod the flock. But Amos also worked to feed the poor, just as Jesus told Peter, “Feed my sheep.”

But the main point here is that Amos had no royal lineage or extensive education — he has never been part of a “company of prophets,” he says. He became great simply by insisting on God’s will and on speaking the truth. Without that, he is nothing; but through his poverty and simplicity, God can do something extraordinary.

St. Paul makes it clear that the same is true for us. Any “specialness” Jesus finds in us is what he put there.

Truly, the Twelve Apostles, and their successors, are richly blessed. But then, so are you and I, says St. Paul. In Christ we too have “every spiritual blessing in the heavens.” That’s a lot of blessing. It is, in fact, limitless blessing, limited only by our willingness to receive it.

Jesus specially chose the Twelve. But God “chose us,” too, says Paul, “before the foundation of the world.” God didn’t carefully create the world, set it in motion, then discover later that it would produce us. He created the world with us in mind. The things we encounter aren’t random hazards — they are planned helps for us, if we use them properly.

Jesus made the Apostles the successors of the 12 tribes of Israel. But God destined us, St. Paul says, for “adoption to himself through Jesus Christ.” Adam and Eve fell for Satan’s temptation to “be like God.” If only they had realized that God wanted that, too, and offered a better way than Satan’s. We play out the same drama with every temptation, which offers us a cheap, counterfeit grace in place of what God wants — to make us his children.

And then, when we fall to Satan’s tricks, he forgives us and restores us by his very own suffering and death. “In him we have redemption by his blood, the forgiveness of transgressions, in accord with the riches of his grace that he lavished upon us,” says Paul.

Jesus gave authority to bishops and prophetic gifts to Amos. But to us he gives everything says St. Paul: “In all wisdom and insight, he has made known to us the mystery of his will in accord with his favor that he set forth in him as a plan for the fullness of times, to sum up all things in Christ, in heaven and on earth.”

When he calls us forward to receive him in the Eucharist, and we return to our pews, we are richer than the richest people on earth, and more blessed than the prophets, even if we have nothing but him.

Image: Lawrence OP, Jesus

Blesses the Apostolic College.