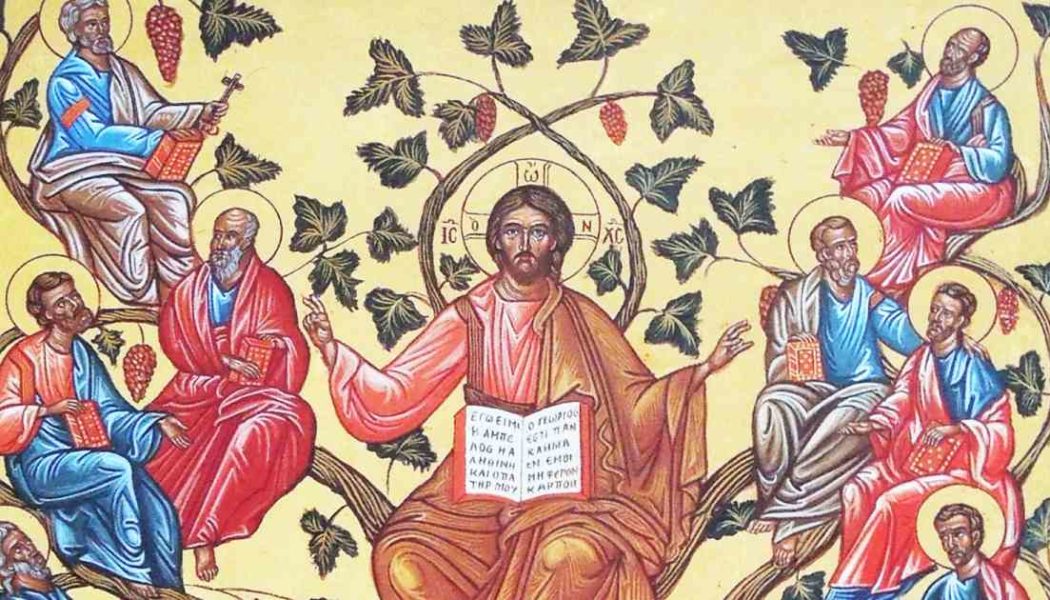

Jesus compares himself to a plant in the Gospel reading for Mass on the Fifth Sunday of Easter, Year B.

In fact, this Gospel comes from the night before he died, in the Last Supper Discourse, after he had spent much of the last week of his life comparing himself — and us — to plant life. After entering Jerusalem, he cursed a fig tree that was providing no fruit, then he compared himself to wheat that is fruitful after it dies, and he repeats again and again how important it is to work in his vineyard.

It all reaches s climax when he stops merely comparing himself to plant-life, and proclaims that what looks like wheat bread is his body and what tastes like wine is his blood — adding that he won’t drink again of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.

In so doing, he is drawing a line from the first days of creation to the new creation in heaven — a line that goes straight through himself, and each of us.

But let’s start with Sunday’s Gospel.

Those who heard Jesus speak these truths for the first time would have had a totally different experience of them from ours — because they heard him outside on a trip to a garden.

Jesus says, “I am the true vine, and my Father is the vine grower. He takes away every branch in me that does not bear fruit and every one that does he prunes so that it bears much fruit.”

These are the first words in the Gospel of John, Chapter 15. The words immediately preceding this, in John 14:31, are: “Get up, let us go.” Then, after a chapters-long discourse by Jesus, we learn that the disciples walked to the Garden of Gethsemane.

That means that Jesus said these words as he walked past the Temple on the way to Kidron Valley. So, right after giving his apostles their first Eucharist, Jesus would have been calling himself the “true vine” as they passed near the place where a giant golden vine with enormous ornamental grapes adorned a Temple gate. And he would have been calling his disciples “branches” that need to be “pared” as he and his apostles headed to a well-tended garden.

They would have heard his “multimedia” lesson loud and clear: “Just as a branch cannot bear fruit on its own unless it remains on the vine, so neither can you unless you remain in me.”

He couldn’t have found a more powerful way to demonstrate that communing with him in the Eucharist would make them larger-than-life shining examples of God’s abundant life.

But he also gave them another, darker, “multimedia” lesson.

As good Jews, they would have known that by calling himself the “true” vine, Jesus meant to contrast himself with Old Testament references to wild and ill-fated grapevines that were analogies for God’s people. And since he had also been telling them parables about vineyards that week, their minds would have gone to Isaiah Chapter Five, the Lord’s “love song concerning his vineyard.”

That chapter tells the story of how the Lord cared for his vineyard — his chosen people — tenderly, but then the day came that he turned to his vines for grapes and was disappointed.

“And now I will tell you what I will do to my vineyard,” he says; “it shall not be pruned or hoed, and briers and thorns shall grow up; I will also command the clouds that they rain no rain upon it.”

Ominously, he proclaims, “I will break down its wall, and it shall be trampled down. I will make it a waste.”

In fact, on their way past the Temple, the disciples may have passed the fig tree Jesus had cursed. It is one of the strangest stories in the Gospels: The morning after he entered Jerusalem, Jesus was hungry and came to a tree for figs, but found none. So he cursed the tree to wither up forever and never again provide figs for anyone.

The lesson of that story was clear to them: First, that Jesus had an extraordinary power over life and death; and second, that he would not to hesitate to use it, based on what fruits they produce.

So his words from Sunday’s Gospel had even more power when he said, “Without me you can do nothing. Anyone who does not remain in me will be thrown out like a branch and wither. People will gather them into a fire and they will be burned.”

The lesson became even more powerful when, within decades of his death, in the year 69 A.D., the Roman commander Titus destroyed the Temple. His soldiers plundered its treasures, plucked its golden grapes, and set it on fire, leaving it a pile of rubble and ash.

But Jesus concludes by emphasizing the positive, saying, “If you remain in me and my words remain in you, ask for whatever you want and it will be done for you. By this is my Father glorified, that you bear much fruit and become my disciples.”

St. John, who wrote Sunday’s Gospel, emphasizes the positive in his epistle, also.

The Second Reading is from the First Letter of John, in which he takes the True Vine lesson out of figurative language and spells it out plainly, saying: “Those who keep his commandments remain in him, and he in them, and the way we know that he remains in us is from the Spirit he gave us.”

Just like a sponge doesn’t work unless it has soaked up some water, and your arm doesn’t work if its blood circulation is cut off, we need the Holy Spirit to permeate us if we are to live Christ’s life fruitfully.

We can’t permeate ourselves with the Spirit; like a sponge or an arm, we can only be a good receptacle for the Spirit. John explains how.

God is love, and the Holy Spirit in particular is the love of the Father and Son. So the Father and Son will stay with us as long as we keep the commandments to love God above all things and our neighbor as ourselves. John puts it this way: “believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and love one another just as he has commanded us.”

If we do that, then we can “reassure our hearts before him … for God is greater than our hearts and knows everything.”

In the spirit of the visual lessons of Jesus, the Church’s readings give us two multimedia lessons of our own.

The First Reading is one. It tells the story of Saul arriving among the Christian people after his conversion. The reading, from Acts, says, “They were all afraid of him, not believing that he was a disciple.” It takes two pieces of evidence for them to trust Paul. First of all, Barnabas took charge of him, and everybody loved Barnabas. But secondly, “He spoke and debated with the Hellenists, but they tried to kill him.”

Seeing Paul’s love for God and neighbor convinced them that he was truly a disciple. The implication is that we will prove to be true disciples of Jesus too if our lives show the same two fruits: encouragement and evangelization.

The second lesson we are given this Sunday is the same one the Apostles got. We have heard that Jesus is the true vine and we are the branches. We know that we can only bear fruit if we abide in him.

At Mass, the priest will say;

“Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the bread we offer you: fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the bread of life.”

and

“Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the wine we offer you: fruit of the vine and work of human hands, it will become our spiritual drink.”

We are offering to God what God has given to us, and he will take what we give him and offer it back, transformed. The Father who regrets that we ate the forbidden fruit to become like gods is giving us heavenly fruit directly from his own hands to become like God.

God is the Heavenly Father, the ground of all being; the Holy Spirit is the Lord, the giver of life; and the Suffering Son is the perfect victim who fulfills all sacrifice. And he is inviting us to get into the communion line today — the same line that St. John joined on the night before Jesus died, the line that St. Barnabas joined after he rose from the dead, and that St. Paul joined after being knocked off his horse.

Jesus wants us to join with him and all those who abide in the One True Vine. And after Mass is over we will be told to get up and do what Paul did: go out into the world and bear fruit that will last.

Image: Flickr, Ted.

![Pope John Paul II’s Soviet spy [WSJ paywall]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/pope-john-paul-iis-soviet-spy-wsj-paywall-327x219.jpg)