It’s providential that as Catholics flock to Indianapolis for the first National Eucharistic Congress in the United States in 83 years, the Church offers the readings for the 16th Sunday or Ordinary Time, Year B.

The readings offer enormous hope, but it’s Christian hope — that means that the hope for peace is available to anyone willing to take up Christ’s offer, with its cross, and follow.

The hope is badly needed. It doesn’t take much imagination to apply to today the words the readings use to describe the world of Biblical times. We are a “vast crowd … like sheep without a shepherd;” we live in a “dark valley” surrounded by enemies; our nation has a “dividing wall of enmity” down the middle; we have seen shepherds who “mislead and scatter the flock.”

Into this comes the National Eucharistic Congress, and Sunday’s Gospel.

Sunday’s Gospel shows just what Jesus is asking of the Church: Work hard, then work more.

In the Gospel from last Sunday, Jesus told his apostles — the first bishops — what their job is: To rely on him alone, to deliver only his message and to expel unclean spirits. This week, the Apostles return to Jesus, weary from their efforts, and report to him “all they had done and taught.”

But even as they report to Jesus, Mark includes the detail that “People were coming and going in great numbers, and they had no opportunity even to eat.”

Two times recently I saw how this works in the lives of priests. First was when a middle-aged priest I know attended a family funeral. While everyone sat and ate at the reception, he spent his time in a series of side meetings with people. Every friend and family member wanted their time with the priest, and every troubled soul wanted him to share their burden.

This starts the moment a man is ordained. I recently saw another priest in action: a friend’s newly ordained son. At the parish hall reception afterwords, as guests ate and rested, the new priest set up a place to give his newly ordained blessing to a long line of people.

His parents realized what I did: Now, he belongs to everyone, not just their family. Or to put it another way, bishops and priests are fathers of enormous families, with the same limitations we lay fathers have. Their lives are not their own, their lives belong to their mission, and their mission is to serve.

The Lord is well aware of how hard it is. He tells the Apostles, tired out from their mission, “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest a while.” But after a boat ride to their vacation spot, they find the place is no longer deserted. Instead, a “vast crowd” got there first, and Jesus, “his heart moved with pity,” extends his mission to them.

Like parents of large families, priests and bishops find that free time is never free, and a vacation is never fully vacation: Vacation simply means being at the service of others in a new location.

It’s important to see why bishops and priests have this burden. It’s the same reason parents do.

The prophet Jeremiah shows exactly what is at stake in the urgent mission of religious leaders in God’s plan of salvation. Preaching on the eve of the fall of Jerusalem, his words in the First Reading describe a situation where self-serving shepherds have neglected their duty.

“Woe to the shepherds who mislead and scatter the flock of my pasture, says the Lord,” Jeremiah prophesies. “You have scattered my sheep and driven them away. You have not cared for them, but I will take care to punish your evil deeds.”

Jeremiah, prophesying as the Babylonians approached Jerusalem to destroy it, saw the consequences of the failure of Jewish leaders. The shepherds of the Chosen People had to be vigilant for the same reason shepherds of sheep have to be vigilant: Enemies are approaching, ready to attack, wolves lurking in the wilderness, watching for weaknesses.

What was true then is true now. Jeremiah had the Babylonians; we have new enemies intent on destroying our institutions. In his Great Commission, Jesus told his apostles to make disciples, baptize and teach the faith. Today, not only are we not making disciples in the West — we’re losing them; our bishops and priests don’t promote baptism, and we are baptizing fewer and fewer children; and catechesis has suffered decades of severe neglect.

But it isn’t all bishops’ and priests’ fault. Parents are meant to be always on duty, but are too often absent or distracted; parents are meant to lead their children in the faith but don’t. Just compare them to Sunday’s Gospel. In the Apostles’ day, families rushed to disturb the rest of Jesus and his men because they were hungry for the truth. In our day, lay people keep their distance.

As a result, we are being overwhelmed by the forces of a new Babylon: Consumerism which demands all our time and money, a state that dismisses human dignity, and a media that undermines what we value most.

But the readings at Mass are filled with hope, and so is the Church in the 21st century.

The doom-and-gloom prophet Jeremiah this Sunday ends with a message of hope. “Behold, the days are coming, says the Lord, that I will raise up a righteous shoot to David; as king he shall reign and govern wisely, he shall do what is just and right in the land,” he prophesies. “In his days Judah shall be saved, Israel shall dwell in security.”

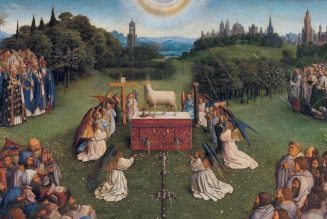

We live in the days Jeremiah is talking about — the days when Jesus Christ is present in the sacraments, and making a bold comeback in the National Eucharistic Revival. This week, there are vast crowds of lay people interrupting the rest of our bishops and priests — at the historic National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis.

For centuries, Jewish people prayed the 23rd Psalm with longing; today, we pray it with gratitude. “Even though I walk through the dark valley, I fear no evil; for you are at my side,” it says.

This week in Indianapolis, there was no reason to imagine Jesus by our side: There he was, in the monstrance. And this Sunday in thousands of parishes nationwide, there is no reason to imagine, either. As we line up in our communion lines, we can look to the baptismal font and pray:

“The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want,

beside restful waters he leads me;

he refreshes my soul.”

Then, returning to our pew, we can pray for the eternal life offered in the Eucharist, saying:

“Only goodness and kindness follow me,

all the days of my life;

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord

for years to come.”

Here, in the Blessed Sacrament Jesus instituted on the night before he died, we see the words of St. Paul fulfilled: “In Christ Jesus you who once were far off have become near by the blood of Christ.”

Jesus is the ultimate example of what an apostle’s mission should be.

In Sunday’s Gospel, “When he disembarked and saw the vast crowd, his heart was moved with pity for them, for they were like sheep without a shepherd, and he began to teach them many things.”

He sees us today, and comes to us, his heart moved with pity. He comes to us in his body, blood, soul and divinity in the Eucharist. And we can listen to him as he does in our day what Mark reports. “He disembarked … and he began to teach them many things.”