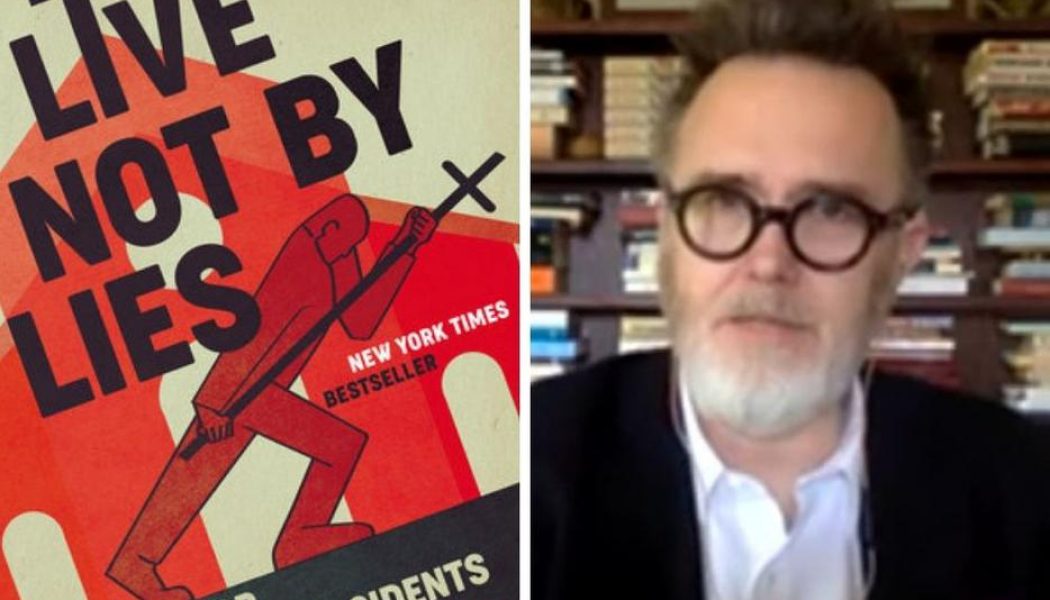

LIVE NOT BY LIES

A Manual for Christian Dissidents

By Rod Dreher

Sentinel, 2020

240 pages, $27

Five years ago, Indiana Gov. Mike Pence suddenly found his state under siege. The White House, tech business leaders and even the NCAA had all expressed their outrage over the Hoosier State’s new Religious Freedom Restoration Act, alleging that it offered business owners a “license to discriminate” against “LGBT” customers. Facing the threat of a damaging national boycott against his state, Pence pledged to amend the law.

But the statute’s most dogged critics on Twitter soon found a fresh target for their fury. The evangelical Christian owners of Memories Pizza in the tiny northern Indiana town of Walkerton told a reporter they would not cater same-sex weddings. Next, the owners received a flood of death threats, amid accusations of the restauranteurs’ bigotry, forcing them to close temporarily.

Most Americans quickly forgot the media storm, but a former Czech dissident and political prisoner who lives in the U.S. with her children was troubled by the attacks on the Christian business. For her, it stirred up memories of mob-fueled violence in her native land as the communist party began its rise to power.

The woman’s son contacted Rod Dreher, the best-selling author of The Benedict Option, to outline the disturbing parallels between Communist Party tactics in the Soviet-controlled East Bloc during the 20th century and growing assaults on free speech, religious liberty and academic freedom in this country by activists marching under the banner of social justice.

At first glance, the claim seemed preposterous. What could contemporary America possibly have in common with a defunct totalitarian police state notorious for its food shortages and concentration camps?

But Dreher contacted other former dissidents and Christians persecuted for their faith and found they shared her sense of dread, believing Americans to be hopelessly naïve.

In his new book, Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents, Dreher shares the fruit of these rich discussions, along with his own research, and explains why we should all be worried about the changes transforming U.S. politics and culture.

“Elites and elite institutions are abandoning old-fashioned liberalism based in defending the rights of the individual,” he writes. It is being replaced “with a progressive creed that regards justice in terms of groups.”

Each group represents a specific sexual or ethnic identity, and the moral framework that once secured a common understanding of good and evil is being reduced to a matter of “power dynamics among the groups.”

The former dissidents, a number of them academics, noted other similarities with life in the Soviet bloc: History is being “rewritten” and language “reinvented,” as social-justice activists continually update the standards used to judge acceptable ideas and behavior. Ordinary people, like the pizza-shop owner, can become “instant pariahs” for violating norms that didn’t exist before.

‘Soft Totalitarianism’

Live Not by Lies doesn’t suggest our political system is headed on precisely the same path as Soviet-style “hard totalitarianism.”

But polls have registered growing support for socialism among the young, and Dreher’s research confirms the impact of left-wing ideology on the media, Big Tech, the academy and even corporate America.

Indeed, the social tumult sparked by the coronavirus pandemic, the racial reckoning that followed the death of George Floyd, and the 2020 presidential election have brought the problems discussed in this book into the forefront of our national conversation, making them more relevant and urgent. So whether or not we find Dreher’s grim forecast persuasive, the insights and solutions presented here are well worth our time.

Looking back on the initial appeal of communism in their native land, the former dissidents explain that its ideology tapped a deep spiritual hunger for new ideals that gave life meaning. Later, when coercive methods were introduced to consolidate state power, the true believers blindly accepted these measures as necessary, reporting on neighbors who defied the state.

Dreher, in turn, looks for parallels in the United States, where organized religion has lost ground, family instability is on the rise and an epidemic of loneliness keeps suicide hotlines busy day and night.

These well-established trends, he argues, leave Americans dangerously vulnerable to a form of “soft totalitarianism,” designed to fulfill both our desire for human connection and our “hunger for a just society, one that vindicates and liberates the historical victims of oppression.”

But scratch below the surface and you’ll find an ideological system that “masquerades as kindness,” while “demonizing dissenters and disfavored demographic groups.”

He takes particular aim at the technology sector and the way it is fostering this political movement in bold and subtle ways.

A viral tweet calling out a public figure or an ordinary citizen for an unverified allegation can result in reputational damage and job loss. Meanwhile, internet search results can be manipulated so that favored political content and organizations rise to the top of our list of results.

Pointing to China’s surveillance state, which monitors citizens’ digital activity and uses rewards and penalties to encourage compliance with party dictums, Dreher suggests that Americans could adapt to similar controls over time. And though our innate individualism might stymie such tactics, he predicts it will be tough for us to give up our tech habits because they have conditioned us to prize convenience, pleasure and social approbation.

The former dissidents tell Dreher that they would never voluntarily share their personal data with anyone, and some avoid smartphones altogether.

Their discipline and vigilance opens a window onto a different, more intentional, kind of existence. Dreher shares their stories and asks us to study their example as we consider how to respond to the advent of soft totalitarianism.

Stories of Resistance

Indeed, this book reminds us that the nonviolent overthrow of Soviet rule happened because a relatively small number of people would not be controlled by state terror, a decision that could lead to imprisonment and death. Many more people, in the routine acts of daily life, opposed a totalitarian lie that rejected the existence of God, the moral law and the redemptive power of suffering.

They created small communities to pray together, discuss politics, publish books and create parallel institutions that would give them the space to think and behave with freedom.

Dreher tells the story of Václav Benda, a Catholic Czech activist and political prisoner, and his wife, Kamilla, who taught their six children “how to read the world around them, and how to understand people and events in terms of right and wrong.”

They made their home a refuge for dissidents and a haven of charity, where their children would learn to love their faith and see that “suffering is a gift” that brings a Christian closer to the Lord.

Václav Benda was a senior member of the leading anti-communist organization Charter 77. But his son, Martin, was most impressed by the haunting scene of his famous father standing alone by the window of their home one night, looking into the street below, worried that Kamilla had been arrested.

“That was the moment when I started to admire my father even more,” Martin tells Dreher. “He was scared, but he did not want his fear to master him.”

Dreher deserves our gratitude for sharing the wisdom and prophetic witness of Václav and Kamilla Benda, among other heroes of this period. They exposed the fault lines of “hard totalitarianism,” inspiring others to join their ranks until the Soviet system collapsed.

And even now their work is not over. For they can inspire those of us who face much smaller trials to find the faith and courage we need to stand together and confront a future full of danger and uncertainty.

Will “soft totalitarianism” define our politics in the future? Not if we don’t let it happen.

[embedded content]