I’m a derivative writer. I wish I were creative. I wish I were ingenious. But my friends and colleagues, and others I admire, are just smarter than I am. This would be sad if it weren’t also consoling. I can’t fix the world, but I don’t need to. Neither do you. In the vast stream of history, individuals rarely seem to matter. . .except in the eyes of God. But of course that’s the one place that really does matter.

So the implications for each of us are worth noting, and they’re captured best by a familiar cleric in a recent interview:

Interviewer: In your opinion, what are the greatest areas of reform needed to renew the Church?

Familiar cleric: Us; all of us. We’re the problem. Structures and policies are important, but people are decisive. In a sense, the focus of real Church reform is always the same: you and me. It’s that simple, and also that difficult. No one really likes to change, because it’s hard. And the essence of conversion is a sea change in the way we think and live. In its Hebrew root, “holy” doesn’t mean “good,” although holy people are always good. Holy means “different from” and “other than.” Christians are meant to be different from and other than the ways of the world. So if we want to reform the Church, we first need to reform ourselves.

Here’s what that means. “Fixing the world,” or at least healing its worst wounds, is the mission of the Church. And while the Church is the soul of the world and always holy, her fertility in any given age depends on “us; all of us.” The holiness of her people translates into the fruitfulness of her mission.

God has an exquisite sense of irony; in the end, the health of a fallen world is ensured by the “un-worldliness” of converted, individual hearts. Or, to borrow a thought from Solzhenitsyn: For the things we can’t achieve, God has appointed others. . .but that doesn’t let you and me off the hook.

We live in unsettled times. Elites in the developed world have been shedding Christianity like dead skin for decades. Their grip on our popular entertainment, news content, and emerging technologies has dragged many millions of otherwise good people along with them. Big corporations wield inordinate political power. Unelected government agencies function, in effect, autonomously. We have a senile presidency unable and unwilling to control the nation’s borders, and a pontificate simultaneously authoritarian and morally ambiguous.

For the Christian believer, the present moment can look daunting, and it’s certainly apocalyptic – “apocalyptic” in the original Greek sense of apokalyptein, which means “to reveal” or “to uncover the concealed.” But uncovering the artfully concealed is good, because the hidden hypocrisies in our institutions, in our leaders, and in ourselves are no longer avoidable.

Jesus said the truth would make us free; not comfortable, but free to think clearly and act faithfully – in other words, to be holy; to act differently from the world. We moderns are fixated on the present. It’s an expensive mistake.

As Catholics, we ignore a Church history that’s rich both in hard lessons and luminous reasons for hope. The process of suffering, purification, and fresh life in the Church is not new; it’s only new for us. But the things we do faithfully now become seeds for Christian renewal in generations to come. What we lack is trust.

My favorite author these days is a former environmental activist and atheist, turned Buddhist and Wiccan, who discovered Christianity and entered the Orthodox Church over the past several years: Paul Kingsnorth. His novel The Wake is a spectacular, if demanding, piece of historical fiction. His articles on his conversion, here and here, rank among the best personal reflections I’ve read in the last decade. In his YouTube interviews (see here, here, and here) he emerges as an astute critic of late modernity. His Substack site, The Abbey of Misrule, is a series of superior commentaries.

The best writers are complex talents. Where Kingsnorth’s journey finally leads him is a tale still unfolding. But the concluding paragraphs of his thoughts on “A Wild Christianity” capture where my own heart is these days, and they’re worth sharing, in part, here:

Is it a desert time again? Of course I think so: I’m the sort of weirdo who spends his birthday in [an Irish saint’s] cave. But I feel like I am being firmly pointed, day after day, back toward the green desert that forms my Christian inheritance, toward that “ardent and active solitude.” Back to the song that is sung quietly through the land by its maker. . .I feel that in another time of crisis and confusion we need to go back to our roots, both literal and spiritual. . .

There is a wild-haired man in the desert clad in camel skin. He is the start of things. He lives on honey and insects, and he calls us to prepare for the coming of one who will baptize not with water but with fire. God, he says, will come in human form. He will be born in a cave, he will walk on the water and battle in the desert and when he comes to the city it will kill him. But that will not be the end of the story. We can’t write the ending to this story. We can only trace the lines on the page in the dim light of the cave mouth. We can only wait patiently for the storm to come over and for the lightning to come down, and illuminate everything.

George Orwell once said that the really great stories are written “by people who are not frightened.” It’s a line worth remembering. We’ve been given, and we’re adding our lives to, the greatest story ever told. God never abandons his people. We just need to act like we believe it.

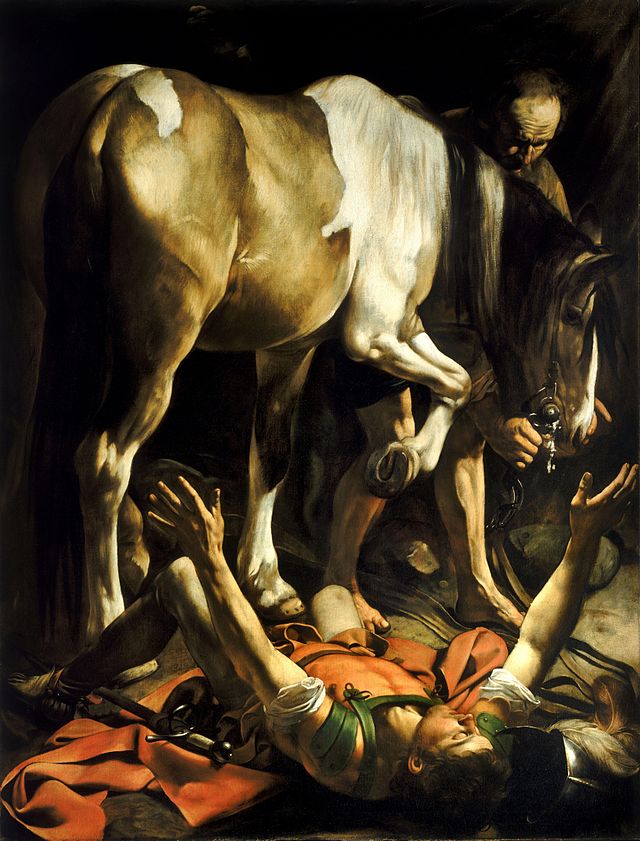

*Image: Conversion on the Way to Damascus, by Caravaggio, 1601 [Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome]

You may also enjoy:

Michael Pakaluk’s Conversion as Paradigm Shift

Joseph R. Wood’s The Inversion of Conversion

The Catholic Thing is a forum for intelligent Catholic commentary. Opinions expressed by writers are solely their own.