Will you make it through this article?

You have been re-programmed in the media-saturated age of consumerism and internet galloping to skim this article. You’re here to grab enough of it to sense a completion after reading, perhaps gaining a sense of gained knowledge, maybe feeling part of a tribe or something.

I’ve been trained as a “content” writer to keep this article skimmable (shallow), but with a feel of depth and wisdom, but in a form that – if we’re honest – will pass quickly as you move on to the next site. Writing for the internet is a specific gig and has very specific (and effective) rubrics. I believe in the power of the written word, naturally, but I know what’s going on here too.

I use very short paragraphs to allow enough white space to accommodate your skimming. Things like that help.

Lest I seem speak down to you, the reader, let’s make sure we acknowledge the dance we’re both in. I make you feel smart by chumming the internet waters with my writing, knowing my niche. You make me feel accomplished by clicking on the article in large numbers. We both move on to the next thing.

Meanwhile, we’re sold to advertise and sell products. We know this. We’ve made peace with it or perhaps given a nihilistic shrug to the unchangeability of it.

So, we dance this routine. We’re in it together.

But I’m asking you to stick with me, and to break The System’s molds. Most articles are “effective” somewhere between 500-1500 words. Right now, you’re less than 300 words in. Will you make it through the whole 2000 words?

The science says is will be hard for you, because by spending a lot of time on the Web you (and I) have been physically changed in the way we receive information, or don’t. And, as Christians, this habit of quick and shallow reading hurts our ability to think, concentrate, and focus – all of which makes it very hard to pray. I think this needs to change.

A Physical Hurt

In his book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr traces how our understanding of the brain has changed.

Scientists once adamantly claimed that after adolescence brains were “set” and no further changes occurred. Further study, however, has shown the “wiring” of the brain, the neurological paths that help receive and process information received through the senses, change constantly based on what we are experiencing daily. As it turns out, the brain is almost always developing and adjusting based on habits and regular encounters. One example many of us might be familiar with would be the heightened senses that can develop once someone becomes blind – that development has actual physical changes that occur in the brain. In that case, the space on the brain used for processing physical sight transitions over to heightened senses of hearing and touch.

The summary is that the brain, far from being “set,” is wildly pliable. Scientists call this “neuroplasticity,” the adaptability and changeability of the brain. As our muscles grow or atrophy based on their use, so too the brain itself adjusts to what we face and experience daily.

Carr notes a paradox in this fact. On the one hand, not being “hard wired” frees us from the idea that we’re just machines cranking out a function. But, once our habits and experiences do engrain themselves, we can easily step on a sort of treadmill, repeating behaviors “mindlessly” whether they are good or bad. As Carr puts it, “Routine activities are carried out ever more quickly and efficiently, while unused circuits are pruned away.”

The implications are likely coming into focus. Our participation in The System that is a media-saturated, consumerist ecosystem, is physically changing our brains to both adapt to it and be hooked on it. (Pause. Consider the implications.)

Many people have observed how checking email and social media releases a dopamine kick in the brain, a sort of “high,” but in the long run the effects are more than just quick bursts of pleasurable distractions we become accustomed or addicted to. The more we participate, the more we are being “wired” to participate. The more we do it, the more we want it, because the more conformed to it we are. The question is, what neurological pathways are turning off while others turn on?

More than a Brain

Before going further, we should note that, as Catholics, we know human persons are more than matter – there is more to thought than the brain. The mind, which is a power of the soul, operates through and with the brain, but the physical matter that is the brain is not the totality of the mind. We are not our brains – we have brains. Unlike the animals and like the angels, we have an intellect and free will, we have self-awareness and human agency. We are neither empty mechanics nor animals of pure instinct. We are body and soul, matter and spirit. The mind harnesses the brain, but it is not the brain alone.

So, let’s return to the question. What is turning on and what is turning off in our brain when we spend too much time on screens?

Carr admits in his own life, and confirms it strongly with scientific research, that (speaking personally) “the Net seems to be chipping away at my capacity for concentration and contemplation.” I underlined that sentence in my book. I can also speak personally that I have known deeply the need for silence, reading, and disconnected leisure, yet my work draws me to the screen, and the screen gladly receives me, molding me to its forms and ways. I too have found that without disciplining the presence of screens, I too have my capacity to concentrate and contemplate hampered.

That’s the crux of the matter…

Christians have always seen the pursuit of God as the ultimate end of all we do. Growing closer to him happens in what is traditionally called “the interior life,” which is the life of the mind and soul in communion with the deeper realities that have God as their true end. It is not a stretch to say that the habits of scanning, scrolling, and skimming are antithetical to the traditional means by which Christians have cultivated the interior life.

Let’s not complicate it. Just picture the icon of Christian learning and holiness: the monk reading silently at a table. He’s not “getting through a book,” he is concentrating and contemplating in his pursuit of God Himself. His interior man, the man that can go below the surface, is very different in habit than the one that Carr describes as “Jet Skiing” over information.

Books are a technology, like screens, but that does not mean that books are simply being replaced by screens. As Marshall McLuhan has persuasively argued in his famous works and quip, “the medium is the message,” new forms of media do not blend with old but displace them – thy are message in themselves. The Web and all that it represents is not a new way to present other messages. It is a new message about life altogether.

Lectio divina (sacred reading), the Rosary, mental prayer, and even the liturgy – all of these things engage the mind in a spirit of concentration and contemplation, the very thing Carr says he can hardly do anymore. The reason it gets harder for you to concentrate and contemplate is that you have trained your brain to not need such things. But you do.

(We’re 1200+ words into this article, and you might have arrived at “the point” and be tempted to click away. Let’s finish though…)

Tempered Brains

Interestingly, St. Thomas Aquinas describes the virtue we need to discipline the mind as falling under “temperance,” which we often think of as a “physical” virtue because it tempers the bodily desires for things like food and sex. The virtue of the mind under temperance is studiousness, which refers to a focused study of truth, a “keen application of the mind,” as Aquinas puts it. As temperance disciplines the hungers of the body, studiousness disciplines the hunger of the mind, because the mind does “hunger” to know, and, owing to our fallen state, needs discipline.

The vice opposed to studiousness is curiositas (curiosity), which is, according to Aquinas, a “sinful study.” For us, two of the ways it can be sinful stand out. The first is by seeking knowledge not for the sake of knowing truth, but to be regarded as knowing truth – to be seen as smart, a sad affectation. A second disorder that is more prevalent is simply inordinate seeking – pursuing the wrong things or just wasting the power of the mind on trivialities. Curiositas is scrolling.

Like temperance broadly, studiousness is not a complicated virtue – deny yourself what is bad or inordinate and engage in what is good and ordered. If The System rewires our brains to be indisposed to receiving the seeds of wisdom and faith that come, ultimately, from God, then we need to turn the screens off. And, if the interior life is cultivated to receive those seeds by silence and worthwhile reading, then we need to shut-up and read.

In Fraternus, the apostolate I work for, we launched a magazine called Sword & Spade for this very reason. The men of Fraternus are keenly aware of their roles as brothers and fathers (a good definition of a true “mentor”), and feel the weight of St. Paul’s words: “…you then who teach others, will you not teach yourself?” (Rom. 2:21). Sword&Spade has general themes that allow a topic to be examined from many angles, and the writers are, overall, men in the trenches of work, family, and leading – they’re real men. We want it to be a stretch, intellectually serious but accessible. We also launched it in print because we acknowledge that the form of the screen itself, as I’ve been arguing, makes it harder to go below the surface. Obviously, we’re using the means of The System, but we’ve taken up the mantra: “use the Matrix to escape the Matrix.”

Sam Guzman has done the audience of this website a favor by writing a book. As much as I’ve enjoyed the website over the years, I can say I’ve more enjoyed getting to know Sam as a person through our somewhat regular phone calls, and the voice of an author almost always gets a different reception in print, and that was a project worth doing.

But, in closing, we ultimately need to band together with this. One of the reasons we want people to get Sword&Spade alongside things like book studies is that reading must be done in silence, alone, but study bears so much more fruit when the fire of conversation blazes in friends. The very idea of a university, as St. John Henry Newman said by his work by that name, is the idea of friends at leisure together, wrestling with the great ideas of great men, of seeking wisdom communally.

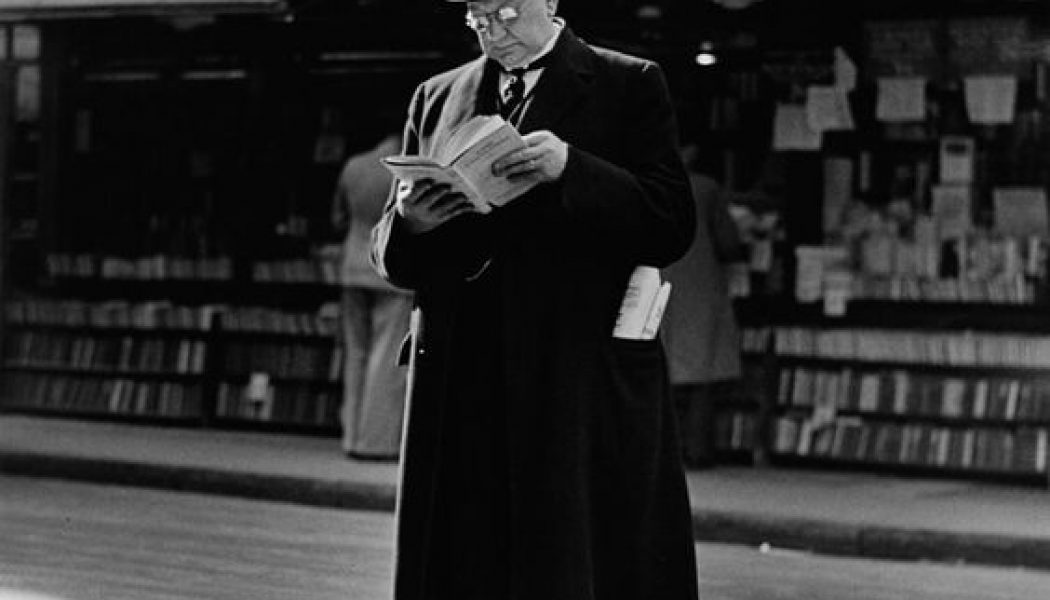

Some of the greatest Christian works in recent centuries have come from small groups of reading friends talking, arguing, and drinking together – think of Lewis, Chesterton, and Belloc, and the beautiful story of John Senior, who revolted against the relativism of 1970’s colleges by creating a program centered around friends discussing classic books like The Odyssey. From that small group, Senior’s students went on to found great institutions like Clear Creek Abbey and Wyoming Catholic College.

In other words, we think our biggest impact is “out there,” in the connection of the Web, but we can likely mount a truer rebellion against The System with a couple of friends, a good book (or magazine!), and some beer.

Jason Craig works and writes from St. Joseph’s Farm in rural North Carolina with his wife Katie and their five kids. Jason is the author of Leaving Boyhood Behind and Director of Program and Training for Fraternus, a mentoring program for young men, and holds a masters degree from the Augustine Institute. He is known to staunchly defend his family’s claim to have invented bourbon.