Nowadays more and more people, Christians and non-Christians alike, are pondering the themes of enchantment and disenchantment. (I haven’t read it yet, but this is the theme of Rod Dreher’s newly released book, Living with Wonder.) Many lament the loss of an enchanted world, the pre-modern world in which people experienced themselves to be caught up in a spiritual drama, a world where people perceived the presence of spiritual realities around them, in which there was no sharp break between the spiritual and the physical. Many people long for a world in which gods and fairies, elves and demons were directly experienced, a world in which blessings and curses, magic and sacraments were not just believed in but perceived to work. Instead, we now have a disenchanted world, a secular world in which we can, of course, choose to believe in the enchanted world of our ancestors, but where that is just one option for belief among many, not something we directly experience.

Last semester, I co-led an online reading group (through The Hildebrand Project) on enchantment and disenchantment. We read key thinkers on what lead to our disenchanted modern world and on possible routes to re-enchantment, including Max Weber (who first popularized these terms), Charles Taylor, Iain McGilchrist, and Dietrich von Hildebrand. Sometimes members of the reading group expressed nostalgia for a world in which a religious worldview was more directly experienced. At other times, people expressed skepticism as to whether anyone ever actually experienced the world that way, or gratitude that we now live in a more predictable and controllable world than our pre-modern ancestors.

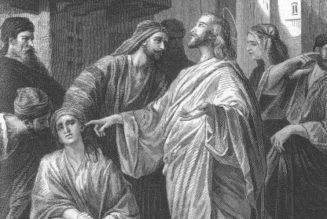

Despite the longing of many Christians (like me) for a more constantly intense, supernatural experience of the world, Christianity stands in an ambivalent relationship to enchantment. Christians believe in all the spiritual realities, but we also cast out demons, and we advocate a way of life based on faith and reason, not on succumbing to exciting forces acting upon us.

When it comes to enchantment, perhaps the biggest challenge for us moderns, including modern Christians, is grasping what it would be like to actually live in an enchanted world. When trying to imagine what an enchanted world would be like, I find it helpful to turn to fiction, to fairy stories and myths, and their continuations in some modern literature, like the novels of the Inklings, Charles Williams, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien.

A Modern Novel and a Novel about Enchantment

I’ve recently been once again (for about the 25th time) reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, this time for a reading group at my church that I’m part of (“The Badly Read Dads”). Tolkien offers a focused, precise account of experiences of various kinds of enchantment throughout the book. When the hobbits are imprisoned by barrow wights, or when Frodo is stabbed by the Black Riders and begins to turn into a wraith, we get a glimpse of dark enchantment: what it would be like to become “porous” (to use Taylor’s term) to the influence of evil spirits, such that their malevolence flows through you and partly controls you. But there are also glimpses of good and holy enchantment, such as when the hobbits are in the house of Tom Bombadil or at Rivendell. But the part of The Fellowship of the Ring that best captures it would like to be under a good enchantment takes place in the elven wood of Lothlórien. This is the forest in which the fellowship takes refuge after their disastrous journey through the mines of Moria. Likewise, when the fellowship leaves that wood, we get an excellent image of moving from an enchanted to a disenchanted world.

While it takes enchantment seriously, Tolkien’s masterpiece is also a modern novel, especially in its depiction of its main characters, the hobbits. While not exactly modern in an entirely contemporary sense, the hobbits are basically rural Englishmen living just prior to the industrial revolution (which, of course, is inflicted upon them by the end of The Return of the King). They have no discernible religion, though they are decent and open to being honorable; they are largely absorbed in creature comforts, albeit mostly of an innocent sort. Other characters, like Gandalf and Tom Bombadil and the elves, make frequent references to divine providence, mostly by saying that some event was chance, “if chance you call it” (Fellowship, 123), or by alluding to “something else at work” (54) in key events. Through these characters, the book exhibits an fundamentally Christian (or, at least, Platonic) theology, with its account of primary and secondary causality, its coupling of providence and freedom, its redemptive and incarnational orientation. But these observations make no deep impression on the hobbits.

Tolkien’s remarkable invention of the hobbits allows us disenchanted moderns to easily insert ourselves in the story. Through a series of wanderings, we are slowly initiated, along with the hobbits, into a more enchanted world. The hobbits never lose their modernity, however: they still often respond to the unusual aspects of their world with irony, they retain an unrelenting practical streak, their interest in the elves always has a sense of the antiquarian or the exotic. But they do become more acclimated to a preternatural world, and by the time the hobbits reach Lothlórien, they (and we) are psychologically ready for experiencing enchantment in a deep sense—at least, as ready as anyone ever can be for the terrible beauty of good enchantment.

Enchantment in Fair Lothlórien

The section of the Fellowship on Lothlórien is a brilliant depiction of what it would like to fall under good enchantment. It’s also thereby a chance for modern Christians (like me) to reflect on whether we really would like to be in an enchanted condition. These chapters show that living in enchantment is not play-acting, not LARPing: it is serious and dangerous, even as it is heartbreakingly beautiful.

Tolkien explicitly connects Lothlórien to enchantment. When the fellowship has reached the heart of the wood, Sam Gamgee says: “It’s sunlight and bright day, right enough. I thought the Elves were all for moon and stars, but this is more elvish than anything I ever heard tell of. I feel as if I was inside of a song, if you take my meaning” (342). To be en-chant-ed is to be “inside of a song” (the same etymology as the title of recent kids’ movie Encanto.)

But to be inside a song, to lose control and be taken up into music of someone else’s making, is perilous. Although the fellowship’s time in Lothlórien is restful and healing, it is not the normal condition for mortals. Before they enter the wood, Boromir expresses his reticence to go there. Boromir seems to believe himself to be disenchanted, but he is really, unbeknownst to himself, becoming porous to dark enchantment. In becoming disenchanted, in trying to see the world as merely a place of natural and human causes, a place that you can control by your own strength (as Boromir believes about Gondor’s military might), you constantly risk being influenced by evil forces and not knowing it. Boromir understands ordinary causes and raw power, but he fears enchantment. He wants “a plain road, though it leads through a hedge of swords” (329), ordinary life and ordinary dangers.

Boromir is right to fear going into Lothlórien. All of Tolkien’s descriptions of the wood, and of the elves in it, are redolent of fairy stories, of stumbling into fairyland, as it has been conceived from the medieval Thomas the Rhymer to the contemporary Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. Lothlórien is akin to Brocéliande or Arroy or any of the other legendary forests of faerie and adventure. It is always perilous to enter these woods, to encounter the “good people.” Some elves or fairies may indeed be good, but they do not think in a human way. You might fall under their spell and be stuck in their land for centuries, not because they are malicious, but because they are entirely other than us.

Enchantment takes you out of the ordinary course of events. Christians who advocate for a more enchanted worldview promote living liturgically, in tune with the cycles of feasts, which in turn follow the cycle of the natural seasons. I’m entirely in agreement with this liturgical way of living. But there is something abnormal about removing oneself from the secular stream of events. In learning to live in a liturgical or enchanted way, one should not lose sight of that strangeness. After they leave Lórien, Sam can’t figure how long they were there. It felt like three nights, or maybe a few more, but it was actually a month. It’s as if “time did not count in there” (379). Such is the temporal experience of enchantment.

But the primary peril of enchantment, as the fellowship experiences it, is the peril of being in immediate contact with beauty (369). Enchantment hides you from the ordinary world and ordinary time, but it opens your eyes to see and delight in things as they are really are. In looking at a tree, Frodo feels the delight of the living tree itself, not seeing it as a forester or carpenter would see it (342), that is, not seeing things in relation to their use, but seeing their whole beauty. There’s no division, in the enchanted world, between what nature does and what artists do to nature: the two are in perfect harmony. “Whether [the elves] made the land, or the land’s made them, it’s hard to say, if you take my meaning. It’s wonderfully quiet here. Nothing seems to be going on, and nobody seems to want it to. If there’s any magic about, it’s right down deep, where I can’t lay my hands on it, in a manner of speaking” (351). Of the cloaks they make, the elves say, “Leaf and branch, water and stone: they have the hue and beauty of all these things under the twilight of Lórien that we love; for we put the thought of all that we love into all that we make” (361).

This beauty, however, is not a pretty picture to contemplate or an occasion to feel the thrill of wonder. That is how some, naively, conceive of enchantment. No, enchantment and beauty always immediately pose you with a choice. To look at beauty is to be instantly tempted to follow your basest desires, or to rise to supra-human transcendence. When the fellowship encounters Galadriel, the Lady of the Wood, they each immediately feel this temptation: to continue to do their duty or to give in to lower desires. Even Galadriel is faced with this temptation, to embrace her own beauty and be a power-hungry queen “beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night!… beautiful beyond enduring, terrible and worshipful,” rather than “a slender elf-woman, clad in simple white, whose gentle voice was soft and sad” (356). To encounter beauty directly is to fall under its spell and to have your heart shattered; the ordinary world can no longer satisfy you. This is the shock and ambiguity of beauty: Galadriel could be Our Lady, nearly a savior, or she could be the seductress, John Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci:

I met a lady in the meads, Full beautiful, a faery's child; Her hair was long, her foot was light, And her eyes were wild.

The peril and danger, the beautiful ambiguity, of Lothlórien are not temporary conditions, which you could eventually get used to—just as the real enchantment of liturgical life should be a constant, perilous drama of having to choose the good and resist the temptation of the good gone wrong, where every beauty we encounter is a potential call to transcendence and a possible snare to perdition. Even other characters who are enchanted feel the constant peril of enchantment. Celeborn, the Lord of Lórien, cautions the fellowship not to go to Fangorn Forest, another enchanted wood. Later, in The Two Towers, Treebeard, who rules that forest, says of Lórien:

I might have said much the same, if you had been going the other way. Do not risk getting entangled in the woods of Laurelindórenan! That is what the Elves used to call it, but now they make the name shorter: Lothlórien they call it. Perhaps they are right: maybe it is fading, not growing. Land of the Valley of Singing Gold, that was it, once upon a time. Now it is the Dreamflower. Ah well! But it is a queer place, and not for just any one to venture in. I am surprised that you ever got out, but much more surprised that you ever got in: that has not happened to strangers for many a year. It is a queer land. And so is this. Folk have come to grief here. Aye, they have, to grief. (456)

If you become enchanted, you will come to grief, though also, hopefully, to joy and wisdom. Once you are in an enchantment, there is a real sense in which you cannot leave: Frodo knows that he will, in some sense, always be in Lórien, even after he leaves physically. But there is also a sense in which you must leave the enchanted wood. Sam recognizes that even with their “magic,” the elves cannot ultimately help them. Having been faced with the choice posed by enchanted beauty, and having made the right choice, mortals cannot stay in the enchanted wood, but must take the gifts received there and depart to do their duty. After they leave Lórien, there are bare woods and brown lands: the dead, disenchanted, secular world, the world beset by raw power and evil, the world in which we mortals are called to have courage and do our duty. This is that ambivalence about enchantment in the Christian life: we are wholly enchanted and wholly disenchanted, entirely in the world but not of it. The fellowship keeps one foot in that enchanted wood, defending the honor of the Lady, living as if in a legend—but they also embrace the ordinary, the everyday, Boromir’s plain road and hedge of spears that is our lot, most of the time, in this vale of tears.