By Clement Harrold

The Babylonian exile is one of the most important events in salvation history. In fact, there are large portions of the Scriptures—the majority of the prophets, for instance—which don’t really make sense until we first learn to appreciate what the exile was and why it matters.

So what is it exactly? Also known as the Bablyonian captivity, the Babylonian exile refers to the deportation of the Jewish people away from their homeland of Judah and into Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (also known as the Chaldean Empire). Though no longer extant, Babylon was then located on the Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq.

This was not the first exile to afflict God’s people. Back in B.C. 722, the mighty Assyrian Empire had completed its conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel. This Assyrian exile left the ten northern tribes in bondage, but the southern kingdom of Judah would retain her independence for another two centuries.

Over the course of those two centuries, however, the southern kingdom of Judah began to imitate the same idolatry and religious corruption which had brought down her northern counterpart. Though God patiently sent the prophets to warn His people to change their ways, those warnings were repeatedly ignored. At long last, judgment came. This time, however, it came at the hands not of the Assyrians but of the Babylonians, who had gradually been increasing their power in the region and who had already conquered Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, in B.C. 612.

The Babylonian exile unfolded over three distinct stages. The first stage occurred during the reign of Jehoiakim, king of Judah, whose ill-advised alliance with Egypt (sworn enemy of Babylon) prompted the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II to lay siege to Jerusalem, the capital city of the southern kingdom of Judah, around the year B.C. 605. In response to this desperate situation, Jehoiakim agreed to pay Nebuchadnezzar large sums of money, and to send members of the Jewish nobility to Babylon as hostages. This was the first stage of the exile, and among those taken into captivity were the prophet Daniel and his companions.

A few years later, Jehoiakim opted to ignore the warnings of the prophet Jeremiah by leading a rebellion against the Babylonian oppressors. Once more, Nebuchadnezzar marched on Jerusalem with his armies, but this time Jehoiakim died before they got there. It was therefore during the brief reign of Jehoiachin, son of Jehoiakim, that the second stage of the exile took place in B.C. 597. Having barely reigned for three months, Jehoiachin was forced into captivity together with thousands of members of Judah’s upper and middle classes. This was the largest wave of the exile, and the prophet Ezekiel was among those taken.

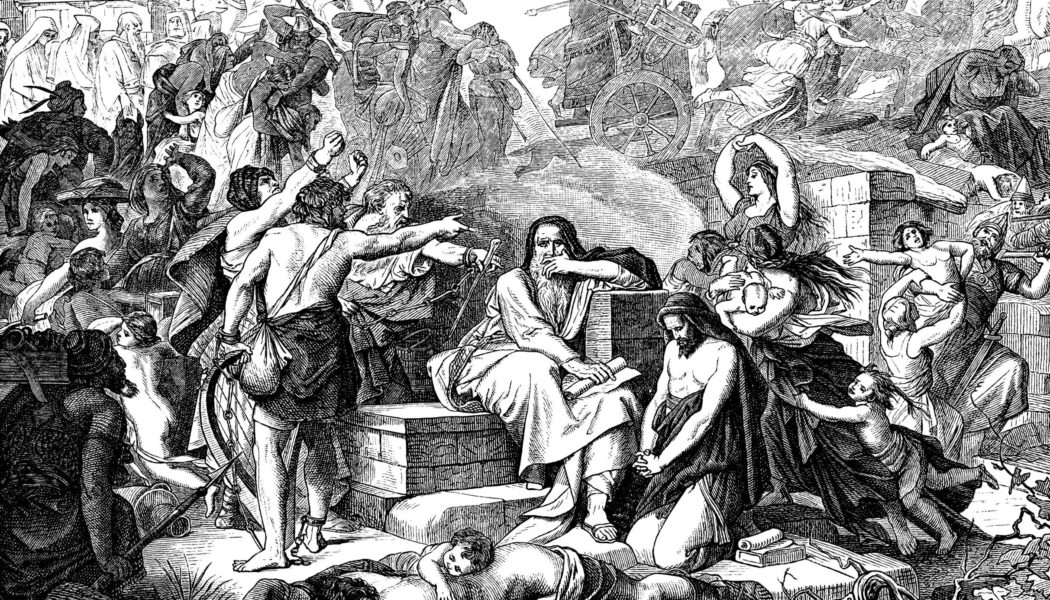

The third and most cataclysmic stage of the exile occurred ten years later, under the reign of Zedekiah, the uncle of Jehoiachin and brother of Jehoiakim, and the last king of Judah. After ruling for eleven years, Zedekiah followed in his brother’s footsteps by attempting to usurp Babylon’s grip on the region. That decision would be his downfall. In B.C. 587 the Babylonian armies arrived at Jerusalem once more, but this time Nebuchadnezzar’s patience had run out. He ordered his forces to destroy the city completely, and Zedekiah was forced to witness the execution of his sons before having his eyes gouged out and being marched off to Babylon together with any Jewish nobility that remained (see 2 Kgs 25).

This final stage of the Babylonian exile proved by far the most decisive and the most traumatic, involving the obliteration not only of the city of Jerusalem, but also of the magnificent Solomonic Temple, the dwelling place of God on earth. In this respect, it is difficult for the modern Christian to comprehend the sense of spiritual and emotional devastation that the Old Testament Jew would have felt upon witnessing the destruction of this building which served as their center of liturgical, political, and economic life.

If we were to wake up tomorrow morning and discover that St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington D.C., and the New York Stock Exchange had all been blown up over night, that might give us a little taste of the sense of national grief experienced by the Jewish people in the year 587. Their promised land had been overrun; their holy places defiled; their people scattered, and thousands of them marched off naked and in chains on the 600 mile journey from Jerusalem to Babylon.

In some terrifying sense, the demolition of the Jerusalem Temple dramatically symbolized the death of the Jewish nation state which had begun under King David five hundred years prior. Even more acutely, its destruction appeared to indicate the defeat of Israel’s God, as His holy place lay in trampled ruins at the feet of heathen armies.

This was the lowest point in Israel’s history, when all hope seemed lost. Yet the larger narrative of the Old Testament reveals that through it all, God had a plan, and the exile became a time of purification and penance through which new life could arise for His people. The Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it this way:

The forgetting of the Law and the infidelity to the covenant end in death: it is the Exile, apparently the failure of the promises, which is in fact the mysterious fidelity of the Savior God and the beginning of a promised restoration, but according to the Spirit. The People of God had to suffer this purification. In God’s plan, the Exile already stands in the shadow of the Cross, and the Remnant of the poor that returns from the Exile is one of the most transparent prefigurations of the Church. (§710)

In the life of the Church today, we continue to reflect on the exilic period as a spiritual symbol for the earthly pilgrimage in which we find ourselves estranged from our heavenly home.

The Babylonian exile matters because it is an integral part of Israel’s story, and therefore of the Church’s story. But it isn’t the end of the story. Even in her gloomiest moments, Israel will continue to be encouraged by the prophets who give voice to the redemption and restoration which Yahweh intends to bring.

Further Reading:

https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03315a.htm

John Bergsma and Brant Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: The Old Testament (Ignatius Press, 2018)

Clement Harrold earned his master’s degree in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 2024, and his bachelor’s from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner.

You Might Also Like

Although many Catholics are familiar with the four Gospels and other writings of the New Testament, for most, reading the Old Testament is like walking into a foreign land. Who wrote these forty-six books? When were they written? Why were they written? What are we to make of their laws, stories, histories, and prophecies? Should the Old Testament be read by itself or in light of the New Testament?

John Bergsma and Brant Pitre offer readable in-depth answers to these questions as they introduce each book of the Old Testament. They not only examine the literature from a historical and cultural perspective but also interpret it theologically, drawing on the New Testament and the faith of the Catholic Church. Unique among introductions, this volume places the Old Testament in its liturgical context, showing how its passages are employed in the current Lectionary used at Mass.