James and John make a bold request in Mark 10: “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory” (Mark 10:37). Jesus invites them to follow him into his Passion but essentially says “no” to this request, because: “to sit at my right hand or at my left is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared” (10:40). What did they mean by this question? Most obviously, they want the two seats of highest honor. They were among the inner circle of three within the disciples (sorry Peter) and wanted to continue this intimacy when Jesus promulgates his reign as Messiah. Beyond honor, it also connotes a position of authority. At the right hand would be the chief the minister, deputed with the government of the king, with the next in command on the left.

Jesus answers enigmatically to this question, but he does acknowledge that someone indeed will fill those roles according to the Father’s will. Who will these select persons be? God does not reveal this to us, but the Church’s artistic tradition puts forward its own answers, ones that have developed over time (see below for our current answer). Let’s take a look at the major stages.

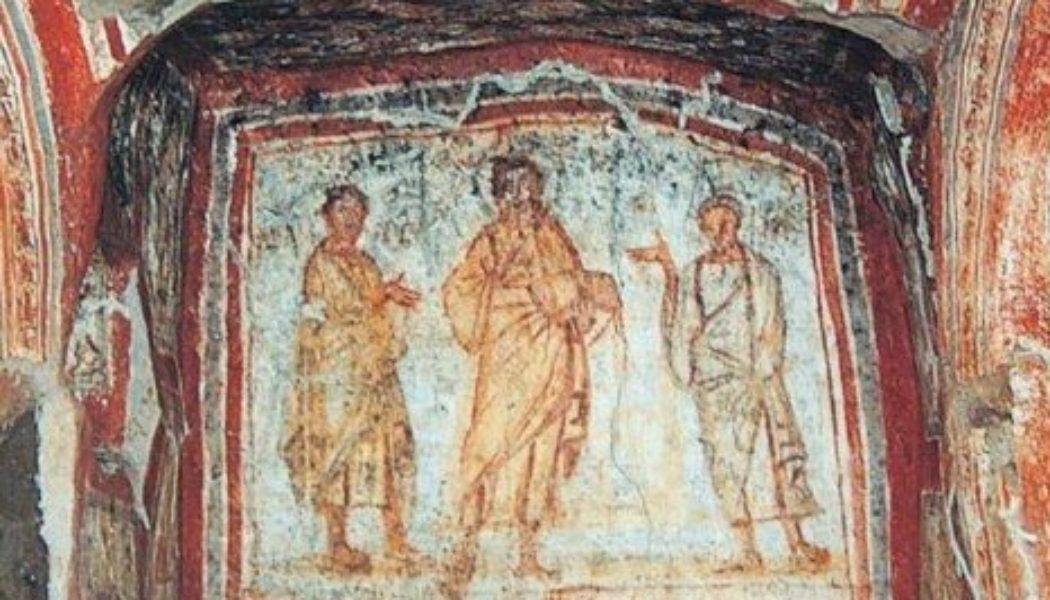

Ionographically, the question is really: who should we turn to primarily in prayer to assist the Church? The first answer in Christian art history is: Peter and Paul. It is no surprise that in Rome, the place of their martyrdom, they would be given pride of place alongside of Christ. As the Christian faith took hold in Rome, the Church saw Christ as its new lord with Peter and Paul as his chief ministers, dressed in Roman fashion. The first two examples here are from the catacombs (Macellinus and Peter on the left and Domitilla in the center), with the apse mosaic of St. Paul’s basilica showing the persistence of their central position in Roman art.

The catacombs also give evidence of Our Lady seated majestically as Queen Mother, with the wisemen coming to do homage. It is not surprising that Mary would be enthroned with Christ, as it was common for the Queen Mother to be seated alongside of her son, the king, as we see Bathsheba next to Solomon in 1 Kings 2:19.

Building upon Mary’s central role as Queen Mother interceding for the Church, we find Mary to the right of Christ in Byzantine and medieval art. To the left, we find Jesus’s cousin, John the Baptist, the greatest man born of woman. The most prominent example can be found in the Deesis (Entreaty) of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople:

Although there is no uniform format for the Eastern iconostasis, it is not uncommon to see Our Lady and John flanking Jesus there.

Examples of the deesis with these two figures can be found in the West as well, as we see in an altarpiece from Dietersdorf, Maestart’s painted version, and the eminent altarpiece of Ghent (which most likely has Our Lady and John flanking God the Father):

Becoming more popular than the deesis, however, the image of Our Lady holding the Christ child retained its prominence, alongside of images of the Crucifixion. Within the latter, we also find Our Lady at Christ’s right and another John, the Evangelist, on his left. They often retain a supplicating gesture akin to the deesis. The first example from Grunewald’s Isenheim altarpiece preserves John the Baptist anachronistically at Christ’s left hand. In Rogier van der Weyden’s image with a red backdrop depicts a more traditional scene of Mary and John standing solo at the two sides of Christ. Finally, in a twist on the more traditional deesis, Cimabue inserts John the Evangelist for the Baptist at the Pisa Duomo, taking the two figures from beneath the Cross and placing them in the heavenly court.

So far we have discovered a small group of the most prominent saints in the Church: Our Lady, Sts. Peter and Paul, John the Baptist, and John the Evangelist. They constitute the privileged few in Catholic art, but also in the liturgy. Think of the traditional confiteor: “I confess to Almighty God, to Blessed Mary Ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the Archangel, to blessed John the Baptist, to the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, to all the Saints.” You may notice one absence in the art presented above: St. Michael. Because he is an angel, we cannot say that he is in contention for sitting at the right or left, but he certainly has a ministering role before the throne of God. A notable example of this can be found in the Beaune altarpiece.

And now for our current artistic solution in the Catholic Church. Beginning in the 19th century, one saint, who has been gaining devotional popularity for centuries, suddenly displaces the others at the left hand of Jesus. Walk into almost any Catholic church and what do you see? On the right hand of Jesus in the tabernacle, a statue or altar dedicated to Our Lady. On his left hand, the same for St. Joseph. It was only in 1870 that Pope Pius IX proclaimed St. Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church in Quemadmodum Deus. His name was added to the canon of the Mass as recently as 1962 (and extended by Francis to other Eucharistic prayers in 2013). Because so many churches were built in North American in the 19th and 20th centuries, this custom became common very quickly (although not universal as the Sacred Heart also appears frequently). This recent practice cannot be found in any of the great churches of antiquity or the Middle Ages.

Alongside of Mary, who we can say holds a settled position at Jesus’s right hand, St. Joseph has become our go-to-guy, far outpacing Sts. Peter and Paul and the two Johns. It’s a serious, recent devotional and artistic shift. Throughout the Middle Ages, we find Joseph appearing in narrative scenes of the New Testament and childhood of Christ. It is during the time of the Renaissance, and especially later in the Baroque period, that devotional art focused on St. Joseph becomes common. Though late to appear, Joseph now assumes a predominate place in Catholic art, one that in my opinion is here to stay.