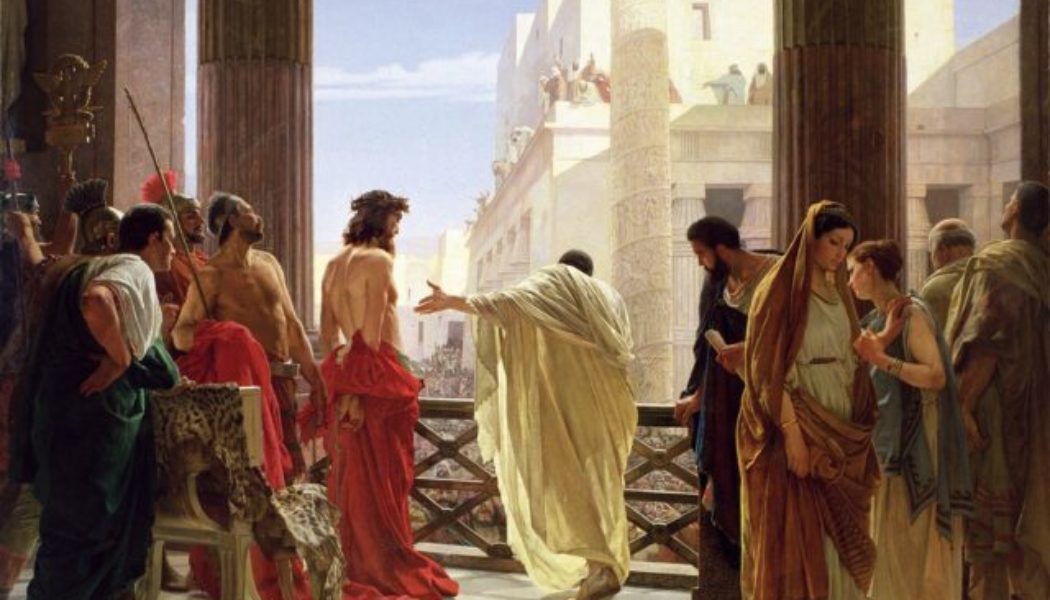

Readers of the four Gospels are struck by the fact that—when Jesus appears before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate—he says nothing in his own defense.

This isn’t just surprising to us; it also was striking to Pilate himself. We’re told:

Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?”

But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge; so that the governor wondered greatly (Matt. 27:13-14).

What should we make of Jesus’ silence? There have been many proposals.

During his trial, Jesus has been silent, a fact that has no genuine analogies in Greek, Roman, or later Christian trials. Jesus’ silence has often been explained with reference to the silence of the Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53:7 (with whom Jesus is thus identified), but Mark and the other Gospel writers do not alert their readers that such an allusion is intended; or with the silence of the righteous sufferer (Pss 38:14–16; 39:9); as fulfilment of Psalm 22:15; as a reflection of Jesus’ portrayal as a sage or teacher of wisdom; as an expression of self-control and perhaps nobility; as Jesus proving that he is in command or showing his contempt for those who sit in judgment over him; or as showing that he is the eschatological judge before the final verdict (Eckhard Schnabel, Mark: An Introduction and Commentary, at 14:60-61a).

But what’s the real explanation?

It helps to note that his appearance before Pilate is not the first time Jesus has been silent. A few hours earlier, when he appeared before the Jewish ruling council, he was similarly quiet:

Now the chief priests and the whole council sought testimony against Jesus to put him to death; but they found none. For many bore false witness against him, and their witness did not agree.

And some stood up and bore false witness against him, saying, “We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.’” Yet not even so did their testimony agree.

And the high priest stood up in their midst, and asked Jesus, “Have you no answer to make? What is it that these men testify against you?”

But he was silent and made no answer (Mark 14:55-61a).

However, there was one thing that did prompt Jesus to make a response:

Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?”

And Jesus said, “I am; and you will see the Son of man sitting at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven” (Mark 14:61b-62).

From this we see that Jesus apparently isn’t interested in responding to the charges made against him—even false ones like him saying that he would destroy the temple—but there is one thing he is interested in answering: the question of his identity.

When directly asked if he is the Christ, the “Son of the Blessed” (i.e., the Son of God), he responds straightforwardly: “I am.” He then identifies himself with the heavenly “Son of Man” figure from Daniel 7:13-14, who was given everlasting dominion over all peoples by God.

At the time, this figure was believed by some Jews to be a divine person who was sometimes referred to as “the lesser Yahweh,” and Jesus’ identification of himself with this figure was regarded by the high priest as blasphemy, so he tore his robes (Mark 14:63-64).

Jesus’ silence before the council on everything except one point is then replicated when he is brought before Pilate:

Pilate asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?”

And he answered him, “You have said so.”

And the chief priests accused him of many things. And Pilate again asked him, “Have you no answer to make? See how many charges they bring against you.”

But Jesus made no further answer, so that Pilate wondered (Mark 14:2-5).

Here again, Jesus is willing to address one question: the issue of his identity. When asked if he is king of the Jews, he responds affirmatively but somewhat cryptically. He could have simply said, “I am”—just as he did when the high priest asked if he was the Christ—the Jewish Messiah—who was understood as a coming king of the Jews.

However, here he says, “You have said so.” This is an acknowledgement that he does have that role, but he’s being cautious for a reason that we will come back to.

Other than this one point, however, Jesus does not respond to any of the other things said against him. Mark does not tell us what the charges were, but Luke fills at least some of them in:

They began to accuse him, saying, “We found this man perverting our nation, and forbidding us to give tribute to Caesar, and saying that he himself is Christ a king. . . . He stirs up the people, teaching throughout all Judea, from Galilee even to this place.” (Luke 23:2-5).

Jesus had no interest in responding to these charges—including the false one that he forbade paying taxes to Caesar (in fact, he had done the exact opposite; Mark 12:17, Luke 20:25).

When Pilate heard that Jesus was Galilean, he then sent him to Herod Antipas, but here again, Jesus was silent:

When Herod saw Jesus, he was very glad, for he had long desired to see him, because he had heard about him, and he was hoping to see some sign done by him. So he questioned him at some length; but he made no answer. The chief priests and the scribes stood by, vehemently accusing him (Luke 23:8-10).

Apparently—unlike the high priest and Pilate—Herod did not raise the issue of Jesus’ identity in a direct enough way, and he ignored the accusations being made.

So what’s the reason for his silence? The answer is found by looking at Jesus’ recent actions.

Jesus has already made three major predictions of his coming death and resurrection (Mark 8:31, 9:30-31; 10:33-34), the most explicit of which is the final one:

Behold, we are going up to Jerusalem; and the Son of man will be delivered to the chief priests and the scribes, and they will condemn him to death, and deliver him to the Gentiles; and they will mock him, and spit upon him, and scourge him, and kill him; and after three days he will rise (Mark 10:33-34).

He thus foresaw that—upon going to Jerusalem—he would be taken into custody by the Jewish authorities, turned over to the Romans, and be sentenced to death.

Upon arriving at Jerusalem, he fulfilled a messianic prophecy from Zechariah 9:9 by triumphantly riding the foal of a donkey into the city, depicting himself as the king of Jerusalem described in Zechariah, and being proclaimed by the joyful crowd as “the king of Israel” (John 12:13), “the king who comes in the name of the Lord” (Luke 19:38), and “the Son of David” (Matt. 21:9). He even refused to silence the crowd when urged to do so by the Pharisees (Luke 19:39-40).

Then he set himself on a collision course with the Jewish temple authorities by driving out of the temple those who bought and sold sacrificial animals and by overturning the tables of the moneychangers (Matt. 21:12-13, Mark 11:15-17, Luke 19:45-46; cf. John 2:14-22).

He was then arrested, tried by the Jewish council, and delivered to Pilate for execution—just as his passion predictions indicate he had planned.

This gives us the key to understanding both Jesus’ silence and his responses to the question of his identity.

He is silent to the charges against him because he is here to die. He is not interested in defending himself against false charges like saying he would destroy the temple or that one should not pay taxes to Caesar. His disciples knew the truth about these matters, but he isn’t interested in convincing the authorities of his innocence. He’s planning on being put to death.

His silence also may be a fulfillment of messianic prophecies, such as Isaiah’s statement about the Suffering Servant:

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he opened not his mouth (Isa. 53:7).

However, fundamentally he is here to die and therefore he needs to be convicted of something that carries the death penalty.

This is why he responds on the question of his identity when the high priest asks if he is the Christ. He frankly says, “I am.” However, claiming to be the Messiah was not guaranteed to be regarded as a crime by the Jewish council, so Jesus does not leave it there: he also claims to be a divine figure, the Son of Man, which he knows that the high priest will regard as blasphemy and worthy of death.

However, claiming to be a divine figure was not necessarily a crime to the Romans. Their emperors—among others—were popularly regarded as divine, and Pilate likely would not have known about the Jewish Son of Man, anyway, so he drops this part in front of Pilate.

Instead, when Pilate asks him if he is king of the Jews, he acknowledges this but in a cryptic way that gives him what we now call “plausible deniability”—i.e., you’ve said that I’m the king of the Jews; I haven’t said that.

John clarifies that Jesus even told Pilate that “My kingship is not of this world” (John 18:36)—indicating that he isn’t interested in political power and thus not interested in challenging the authority of Caesar, who then held the authority to appoint Jewish kings.

Pilate thus emerges from his conference with Jesus and tells the Jewish authorities that he doesn’t find Jesus guilty of any crime, which causes the authorities to stir up the crowd to demand Jesus’ execution, and Pilate finally capitulates.

Jesus thus gives Pilate only an acknowledgement of his royal status, but it’s cryptic and he clarifies that he’s not interested in political power.

This makes it appear that Jesus wanted responsibility for his execution to ultimately fall on the Jewish authorities, in accordance with messianic prophecy. As Jesus himself said:

Have you not read this Scripture: “The very stone which the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; this was the Lord’s doing, and it is marvelous in our eyes”? (Mark 12:10-11; quoting Psalm 118:22-23).

We thus see Jesus performing a complex set of maneuvers in order to fulfill his mission: He is silent against false charges because he is here to die; he says enough to the Jewish authorities to bring about his conviction; he is truthful with the Roman authorities about his lack of interest in worldly rule; and ultimately it is the action of the Jewish authorities that causes Pilate to capitulate and order his execution—in accordance with the prophecy that the Jewish authorities (the builders) would reject Jesus (the stone).