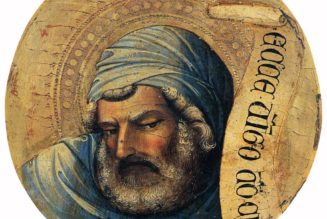

Most famous outside the Church for his line “and always keep ahold of nurse, for fear of finding something worse,” Hilaire Belloc wrote dozens of books of history, memoir, theology, travel and pilgrimage, and politics, as well as many novels and poems. He briefly served in Parliament as well. He was born in France in 1870 (his newly widowed mother moved the family to England when he was five) and died in 1953.

With his friend G. K. Chesterton, he was one of the major public intellectuals of his day. Among his greatest accomplishments was his demolition of H. G. Wells’ progressive fantasy, the best-selling Outline of History. With Chesterton, he developed a distinctive political and economic system they called Distributism, which was neither socialist nor capitalist, and desired the wide possession of property.

The line at the beginning comes from the story “Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion” in his famous children’s book Cautionary Tales. The words below come from Letters From Hilaire Belloc.

To an older man who had lost his brother

You know all there is to know, in this life, upon death. For all that is to be known is the rock of Christian doctrine which I know you hold and which alone makes it possible to write at all. That doctrine is often said to console. Its value lies not in this but in its verity. And men today, to whom one cannot write from lack of a common ground, have lost reality by losing the Faith. Through doctrine we can pray for our dead and hold even, in some dim way, communion with them. Certainly we can serve them. For us alone who accept the sole tradition of life, our dead remain for all that is lost returns. For that is also a doctrine.

To a friend also growing old

After a certain time and experience all life is retrospection and duty. One has to hold on for the sake of the others and one must not long make of any mundane thing a necessity. The end of life, the second half, is a liquidation but of course if they don’t reward us afterwards it will be a Bloody Sell. The Little Flower says, “I trust as much in the Justice of God as in his Mercy.”

To a woman who had lost her father

I beg you not to over-grieve. The advantage of the Faith in this principal trial of life is that the Faith is reality, and that through it all falls into a right perspective. That is not a consolation — mere consolation is a drug and to be despised — it is the strength of truth. We know how important lie is (and no one knows that outside the Faith) but we also know that we are immortal and that those we love are immortal, and the the necessary condition, before eternity, is loss and change, and that we can regard them in the light of their final revelation and of re-union with what we love.

I do not say this because I would make less the enormity of these blows. I know them as well as anyone and I reeled under them. But with the Faith they can be borne. they take on their right value. They are not final. I am going to have a Mass said for your father at once. . . . God bless you, my dear, and keep you well and secure in the business of this sad world till you also attain felicity or ever.

On growing old

I think, though we don’t know, that with age the mind acquires greater depth and the essential isolation of life is apparent to it. It is like seeing the stars at night which you can’t see by day. It is not a pleasant thought, but on the other hand it all hangs together for one doesn’t appreciate the vile insufficiency of this world till one has nearly done with it.

On the dead who have gone before

I have come to that stage in life in which the death of such few friends as remain must be expected, but it is in a way more grievous than in earlier life, both because the diminishing number becomes so small, and because the imagination is less vivid. On the other hand, with age philosophy grows firmer, and one is more fixedly certain that all the trouble is for us, nos qui vivimus, and all the benefits for the dead. I have much more than I used to have the feeling that they have become alive, and we are only half alive. This is particularly true with the death of the exceptionally good.

Belloc’s friend G. K. Chesterton’s insights on death and dying can be read here.

The picture is a portrait of Belloc taken by Emil Otto Hoppé in 1915, which is part of the National Portrait Gallery’s collection.