Hey everybody,

Welcome to the Tuesday Pillar Post.

The Main Event

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’ve probably read already the big news from Vatican City in recent days:

On Saturday, the Vatican City state’s Promoter of Justice — essentially its public prosecutor — announced the indictment of ten people for embezzlement, extortion, fraud, abuse of office, money laundering, and a smattering of other crimes. Four companies belonging to some of the accused were also indicted — most likely so that if their owners are convicted, damages can be assessed and seized from their corporate assets.

All those indictments are connected to the sprawling Vatican financial scandal that we at The Pillar have been covering in-depth since we launched, and that we of The Pillar have been covering in-depth as journalists for a couple of years now.

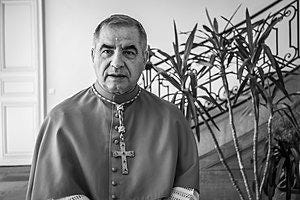

Among the indicted is Cardinal Angelo Becciu, who will be the first member of the College of Cardinals to be tried by the Church for financial crimes since Cardinal Nicholas Coscia faced trial in 1732.

(I’ll have more about Cardinal Coscia at the end of the newsletter.)

The first hearing of the criminal trial will take place on July 27; it will very likely set a preliminary schedule for subsequent hearings, most of which will not take place until after the Holy See’s August recess, during which everyone who lives there gets out of Rome for a month.

It is a very big change in ecclesiastical culture that a cardinal is facing a Vatican City criminal court. But Rome would be a “world turned upside down” if curial officials had the temerity to conduct his trial in August — no Roman churchman would ever imagine such an indecency. So, look for things to really get started in September, when civilized Vatican bureaucrats return to work.

Read The Pillar’s breaking coverage from Saturday about the indictments here.

And if you want to read a brief history of the entire London financial scandal, which we at The Pillar published in January, you can read it here. Of course, now that most of the people mentioned in that history are facing trial, it’s a bit out of date, but it will give you the backstory pretty clearly.

‘Say what you need to say’

Since the indictments were handed down, we’ve put together a few additional reports to help you understand what’s coming next.

First, a word about the Vatican’s London investment property which began the current set of scandals: The actual building itself, 60 Sloane Avenue, is owned through a holding company called London 60 SA Limited. (The name is not especially creative; SA stands for Sloane Avenue.)

London 60 SA Limited is owned by the Vatican Secretariat of State. But the company has a governance structure with a limited number of registered directors — essentially board members. The problem is that while the Secretariat of State initially appointed four such members, three of them were removed in 2019, leaving only one: An Italian architect named Luciano Capaldo.

It’s not clear how Capaldo got this job. It’s also not clear what he actually does in the job, or if he’s being paid, for that matter. What is clear is that Capaldo has a history of business ties to a number of other figures in the Vatican financial scandal, especially Gianluigi Torzi, the man accused of using the building to extort the Holy See for millions.

The Holy See has declined to comment on The Pillar’s questions about why Capaldo is the only registered director of its holding company, or whether it’s prudent to leave him in the job. But it is fascinating that Capaldo has remained — for better or for worse — in a singularly important post from which to watch the dominoes around London 60 SA Ltd begin to fall.

Oh, and, of course, there are also some unusual unanswered questions about Capaldo’s citizenship — it’s probably nothing, but it is unusual.

Read all about Luciano Capaldo here.

—

We’ve talked about the looming possibility of a Vatican financial crimes trial for the past several months, and we’ve been asked frequently just who among the rotating cast of characters has a chance of doing serious jail time — and whether Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Holy See’s Secretary of State, will face accusations of his own.

Both are fair questions.

The truth is that a number of figures face the prospect of incarceration. And Parolin may indeed have to face up to questions about his own involvement in the complicated transactions at the heart of the trial — especially since everything under investigation took place within the Vatican department run by Parolin, and because the cardinal’s explanations of his own role in things have not always been, as it were, internally consistent.

But the substance of the trial, and the possibility of jail sentences handed down, depends a lot on which of the now-indicted figures decides to start working out a deal with Vatican prosecutors — which would mean cooperating with their pursuit of convictions, and providing testimony against colleagues, collaborators, and even supervisors.

He noted that some figures could prove especially troublesome for Cardinal Parolin:

But, as those charged with deceiving him appear in court and are left fighting for their freedom and futures, Parolin’s apparently invincible ignorance about what was going on in the department he is in charge of running is likely to be keenly disputed in court.

Even if Parolin does convince the court he never understood what he was signing, he may still be left with much to lose: proving his ignorance may rely on his ability to show he is incapable of running his own department.”

Read the entire analysis here.

Further afield

Poland has a reputation as one of the strongest Catholic countries in Europe, so its own unfolding abuse crisis has implications well beyond its borders.

Our friend Stephen White, who works on issues related to clerical sexual abuse as executive director of The Catholic Project, a CUA-sponsored effort to respond to clerical abuse misconduct, read the report from Poland’s bishops carefully.

We asked him to break it down for us by the numbers, and tell us what it might mean:

Given that Poland currently has some 30,000 priests (roughly a quarter of all priests in Europe) and some 33,000,000 Catholics (well over 90% of the country), the reported numbers remain relatively low when compared to some other countries.

…

But the reported numbers hardly paint the whole picture of the abuse crisis in Poland…The coordinator for the protection of children and youth for the Polish bishops, Fr. Adam Żak, SJ, offered a sobering reminder last week that reports of abuse are likely to continue to climb: “The trend is not downward; it remains at a fairly high level of numbers.”

There are other indicators—beyond reporting statistics—of just how serious the crisis of clerical sexual abuse is for Poland.

Read Stephen’s sobering analysis here.

—

And you have probably read that in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, a military conflict has left two million people displaced.

Here’s the situation in a nutshell, from CRS:

Ethiopia is now reeling from a recent war in the Tigray region that has displaced millions of people and caused widespread food, shelter and healthcare needs. The conflict continues to persist in certain parts of the region, making it difficult at times for humanitarian aid to reach people in great need.

For more about what’s happening, and what the Church is doing to help, read this interview.

Varia

—

As most readers know, a group of 60 Catholic Congressional Democrats released a “Statement of Principles” last month, in response to the prospect of a document on Eucharistic coherence drafted by the U.S. bishops.

Observers have noted that the statement was released almost immediately after it was announced that the bishops had voted to draft their document, and they’ve asked how the group got their statement together and published so quickly.

While a variety of theories have been floated, one astute reader of The Pillar found the answer.

Much of the 2021 “Statement of Principles” was lifted from a 2006 statement signed by 55 members of the House. The original text of that statement has been taken off the website on which it was published, but evidence of it can be found online.

There is, however, a key difference between 2006 and 2021, in one crucial paragraph. See if you can spot it:

The 2006 document:

“We envision a world in which every child belongs to a loving family and agree with the Catholic Church about the value of human life and the undesirability of abortion – we do not celebrate its practice. Each of us is committed to reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies and creating an environment with policies that encourage pregnancies to be carried to term…”

The 2021 document:

“We envision a world in which every child belongs to a loving family and agree with the Catholic Church about the value of human life. Each of us is committed to reducing the number of unintended pregnancies and creating an environment with policies that encourage pregnancies to be carried to term…”

Did you catch it?

Excluded from the 2021 document is this phrase: “…and the undesirability of abortion – we do not celebrate its practice…”

As to why that phrase was cut, we have not yet gotten a precise answer yet. But it is worth asking.

—

As you might have learned from Michelle’s reporting on the subject, the Tigray region of Ethiopia — and indeed the country on the whole — is facing untold atrocities amid a humanitarian and refugee crisis of epic proportions.

One key first group to sound the alarm on the crisis has been “Aid to the Church in Need,” a pontifical foundation which provides aid and support to Catholic apostolic and charitable projects in some of the most struggling parts of the world.

We want to help their work. And we want to invite you to help too. So from today until next Tuesday, we’re going to give Aid to the Church in Need the first $10 of every new paid subscription to The Pillar.

If you’ve been meaning to upgrade from a free subscription to a paid one, or meaning to encourage a friend to pay for The Pillar, do it now, because we’re giving $10 to Aid to the Church in Need for every new paid subscription that comes in this week.

Or tell a friend:

(Of course, being craven and cynical journalists, Ed and I worked out that you could compel us to give ACN more than you pay The Pillar by signing up to pay a monthly $5, waiting for us to send ACN $10, and then canceling your subscription. I suppose if you really want to do that, we’re not going to stop you. But hopefully your conscience will get the better of you.)

For serious, ACN does important things, and we’re going to send them money. Subscribe, and some of what we send will be your money:

—

Niccolò Coscia became a baptized Christian in 1682, a priest in 1705, a civil and canon lawyer in 1715, a bishop in 1724, and a cardinal one year later, in 1725. But he was excommunicated in 1733.

Here’s what happened:

Coscia became a cardinal during the pontificate of Benedict XIII, a very pious Dominican who lived simply and who focused almost entirely on the spiritual dimension of the papacy. Benedict had a reputation for near-indifference to his temporal responsibilities, including the governance of the papal states, which he entrusted entirely to his secretary, Cardinal Coscia.

Coscia became corrupt, and abused his position to amass a personal fortune. He also amassed enemies, both among the people of Rome, who disliked his administration, and among the College of Cardinals, whose members saw and opposed his corruption. Cardinals presented evidence against Coscia in the Vatican, but the pontiff continued to trust his cardinal secretary.

Soon after Benedict died in 1730, Coscia fled Rome, fearing that without his papal protector he might face consequences for corruption. He came back to Rome a few months later to participate in the conclave, which, deadlocked, took more than four months to elect a pope.

Pope Clement XII was elected in August 1730, and ordered an investigation into charges of corruption and simony at the Holy See. A trial against Coscia began in 1732, and in 1733, he was sentenced to be excommunicated and imprisoned at Castello Sant’Angelo for extortion, forgery, and treason.

The cardinal’s health suffered while he was in prison, which may have tempered him. His excommunication was remitted in 1734, at his request. He was freed from prison when Pope Clement died in 1740, and, still a cardinal, was allowed to participate in the conclave of that year. The next pope, Benedict XIV, made a review of Cardinal Coscia’s situation, forgave the time remaining on his prison sentence, and restored him to the College of Cardinals.

(Time is not really a Nietzchean flat circle, but history really is a spiral.)

Cardinal Coscia died in quiet retirement in 1755. Whether he repented — whether he was contrite — is known only to God. And that question, for Cardinal Coscia and for us, is the only one that finally matters.

On that note, join us in prayer for the pope, for those who will face trial at the Vatican, and that each of us will be prepared for the judgment which none of us will escape, and which matters more than any other.

Pray for us, as we pray for you. Have a great week!

Sincerely yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

ed. note: Coscia became a cardinal during the papacy of Benedict XIII, not Benedict XII. The Pillar has corrected this egregious error, and offers apologies to our readers.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity