Jesus does more than heal 10 lepers in the Gospel this Sunday, the 28th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C.

He teaches us to be grateful for his healing touch in our lives and, according to St. Augustine, explains how to heal division and dissent. Both are lessons every Catholic needs to learn today.

Jesus is continuing his resolute journey to Jerusalem when he hears distant voices crying out.

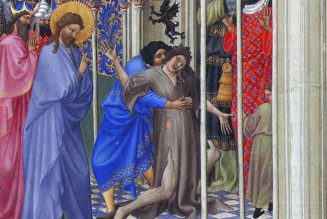

Luke tells us 10 lepers “stood at a distance” and shouted, “Jesus, Master! Have pity on us.” Jesus healed them from a distance too. The Gospel says, “When he saw them, he said, ‘Go show yourselves to the priest.” They did, and were healed on the way.

Leprosy has been all but eradicated today, but the focus on leprosy in Scripture is still relevant, according to Pope Benedict XVI. Leprosy was uncleanness in the Old Testament, and it separated the sufferer from the community of the faithful. To be re-integrated into the community, the leper had to get a bill of clean health from the priest.

Today, “it is not the physical illness of leprosy, as stated by the old norms, that separates us from him, but sin, spiritual and moral evil,” he said. “If the sins that we commit are not confessed with humility and trust in the divine mercy, they can even reach the point of producing the death of the soul.”

Once you think of leprosy as a sign of sin, you can relate to the actions of the leper who returned and “fell at the feet of Jesus and thanked him.”

St. Bede explains that “he fell upon his face, because he blushes with shame when he remembers the evils he had committed. And he is commanded to rise and walk, because he who, knowing his own weakness, lies lowly on the ground, is led to advance by the consolation of the divine word to mighty deeds.”

So, the first lesson of the story is about how to handle mortal sin.

Start by calling out to Jesus Christ in prayer, even though it seems he is “at a distance.” Many people refuse to pray when they are in a state of mortal sin, Father Jacques Phillippe points out in his book Searching for and Maintaining Peace. They feel like Jesus is totally uninterested in hearing from them because they have broken faith with him. His advice is that they should continue to pray as usual, despite of — in fact because of — their shame, and then go to confession as soon as possible.

That raises another problem in the Church today: The loss of the sense of sin is the problem of our time, according to Pope Pius XII, Paul VI, John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis. And yet the Church in the West — from cardinal archbishops to parents and lay catechists — has done very little to teach people about mortal sin and the need for confession.

That means that the Church as we know it is more like the nine lepers who took Jesus’s healing for granted than the one who came back overwhelmed with gratitude.

But there is another, related lesson, according to St. Augustine.

The lepers call out to Jesus as their “master,” or “teacher.” “But by their calling him Teacher,” wrote St. Augustine, “I think it is plainly implied that leprosy is truly the false doctrine which the good teacher may wash away.”

Just as the Church heals sin by the sacraments, the Church addresses error by its teaching office, Augustine writes. The story in Luke is meant to tell us how a true follower of the Church acts, he says:

“Whoever then follows true and sound doctrine in the fellowship of the Church, proclaiming himself to be free from the confusion of lies, as it were from leprosy, yet still ungrateful to his Cleanser does not prostrate himself with pious humility of thanksgiving, is like to those of whom St. Paul says, ‘though they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him’” (Rom. 1:21.).

In our lives, factionalism and dissent works the same way it did for the lepers. The lepers banded together even though at least one was the sworn enemy of the others, a Samaritan. Tragedy united them in a common need which, together, they looked to Jesus to fulfill. Once he provided it, though, they went their separate ways.

After the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, we were like those lepers, clinging together in a common trauma. The fierce fierce political disagreements of the 2000 election and its aftermath disappeared and all were as one in America. Tragedy united us. But then we drifted apart and our divisions hardened.

We can see those divisions very clearly in the Church today. On one extreme, there are Catholics openly hostile to the Second Vatican Council and Pope Francis, whom they pointedly call by his pre-papal name “Bergoglio,” and publicly denigrate at every opportunity. On the other extreme are those in charge of social media for the “Synod on Synodality,” who have posted cartoons openly hostile to the clarity of the Church’s teaching on marriage and the priesthood.

Both reactions come from a loss of the sense of sin. The Catechism lists “sins that cry to heaven.” Conservative dissenters are often associated with the sin of rejecting the foreigner and underpaying immigrant and overseas labor. Liberal dissenters are often associated with the other two sins that cry to heaven: embracing the culture of death and the sin of sodomy.

Most of us are somewhere in between — but all of us have the same instructions from the Lord: Go and bow at the feet of Christ in all humility and obedience and thank him for the magisterium.

This is only possible with real gratitude.

St. Paul speaks to each of us, the lepers of the 21st century, with a succinct summing up of what should make us so grateful, humble, and ready to obey God.

“Remember Jesus Christ, raised from the dead, a descendant of David: such is my gospel, for which I am suffering, even to the point of chains, like a criminal,” he says. “If we have died with him, we shall also live with him; if we persevere we shall also reign with him.”

If it is hard for us to be as alive with faith and gratitude as Paul is, remember: Paul believed what he did because he met Jesus Christ on the road to Damascus after Jesus was risen from the dead. We believe what we do because generations after him have met him and suffered for him, too.

If the words of the Gospel go in one ear and out the other, it is because we haven’t met Jesus Christ. The answer is to do as the 10 lepers did and call out for him, even if he seems far off. He will hear our prayer.

Our next move, then, should be to thank him daily, like the military leader Naaman in the First Reading who was so grateful for what Jesus did for him that he wanted to take a cartload of earth from the Holy Land back with him to Syria so that he could worship the God of Israel.

“The Lord has revealed to the nations his saving power,” said Sunday’s Psalm, so we “Sing to the Lord a new song for he has done wondrous deeds.”

This is what each of us should feel after meeting Jesus, said the fourth century bishop Eusebius of Caesarea.

“Let me now sing the new song since after these grim and horrifying scenes and narratives, I was now privileged to see and to celebrate what many righteous people and martyrs of God before me desired to see but did not see and to hear but did not hear,” he wrote. “The present circumstances are more than I deserve. I have been totally astonished at the magnitude of grace he has conferred, and offer him my total awe and worship.”

Only that kind of gratitude, from left and right, will heal the Church.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity