The most recent documents governing priestly formation in the United States, the Ratio Fundamentalis and the sixth edition of the Program of Priestly Formation, place a renewed emphasis on the foundational importance of the royal priesthood of the baptized in the formation of the ministerial priest. Both documents point to what is now called the “discipleship phase” early in formation wherein “systematic formation as a disciple of Jesus Christ is the aim” (PPF §32). Just so, the Ratio characterizes the entire life of the ministerial priest as a “singular ‘journey of discipleship,’ which begins at Baptism, is perfected through the other sacraments of Christian initiation, comes to be appreciated as the center of one’s life at the beginning of Seminary formation, and continues through the whole of life” (§3).

Indeed, the formation of ministerial priests begins not upon the man’s entrance into seminary, but at baptism when he is made a member of the Mystical Body of Christ and given his baptismal share in the one priesthood of Jesus Christ. These initial stages of formation are not ordered particularly towards pastoral service, but towards helping a man to deepen his baptismal priestly identity, and to “stay with Him” (Mark 3:14). This phase is to help a man configure his heart, mind, soul, and strength to that of the Lord Jesus—to be perfected in the art of the sequela Christi and becoming perfect as the Father is perfect. Nothing about this phase is distinctly ministerial, but it is distinctively baptismal.

This renewed emphasis in the formation documents follows the model of ministerial priesthood present by the Second Vatican Council, elaborated by the post-conciliar pontiffs, and recently articulated beautifully by Pope Francis: “Priests never stop being disciples of Jesus, they never stop following Him. Thus, formation understood as discipleship sustains the ordained minister his entire life and regards his entire person and his ministry” and describes “the path of the disciple priest, in love with his Lord and steadfastly following Him.”[1] In other words, the priestly-disciple identity and mission given when a man is baptized is the foundational identity and mission for the ministerial priest’s identity. Thus, the beginnings of seminary formation must focus on a careful and intentional unfolding of the mysteries of one’s own baptismal graces and extant priestly identity, rather than future priestly identity.

Many of the catastrophic failures among those ordained ministerial priests in recent decades are not primarily failures of the ministerial priestly vocation—although they are that—but are, first and foremost, transgressions of the baptized priestly identity, of the priestly holiness proper to all Christians. Failure to live out one’s promise of priestly celibacy is even more fundamentally an offense to Christian chastity. Thirst for power is as much a violation of the Sermon on the Mount given to all Christians as it is a failure in priestly promises or adherence to the directories for the life of priests. The new documents’ emphasis on the need for deepened discipleship is in part because of the public failures of ministerial priests to recognize and abide by their baptized identities.

The renewed liturgical Rite of Baptism of Children following the Second Vatican Council manifests the theology of the baptismal priesthood beautifully and emphasizes through prayer and ritual gestures the priestly nature of the baptized. After the sacramental baptism, the ritual describes four “explanatory rites,” which, while adding nothing to the sacramental validity of baptism, serve to unfold the meaning of what has just taken place. They describe various elements of the Christian life and help to demonstrate the priestly identity of the Christian. Similarly, after a man is ordained a priest, another series of explanatory rites takes place, which unfold more deeply the meaning of his ordination.[2] Each of the explanatory rites of the priestly ordination rite has a parallel in the baptismal rites, which clarify the connections and distinctions between the ministerial and baptized shares in the one priesthood of Jesus Christ.

Both liturgies include an anointing with sacred chrism (on the head or hands), a clothing with a garment (baptismal garment or chasuble) used to signify a new identity and obligations, an ecclesial expression of the vocation (the handing on of a lighted candle and the fraternal sign of peace), and a symbolic expression of the means of sacrifice (the ephphatha prayer and the traditio instrumentorum). Those writing the reformed liturgical rites might not have intended these connections explicitly, but these rites (and the connections between them) capture and express the lex credendi of the Church, and thus are worthy of our study.

The Clothing with a New Garment as an Expression of New Identity and Duties

After the anointing, a newly baptized child is given a new garment, which is required to be white. The minister prays:

N., you have become a new creation

and have clothed yourself in Christ.

May this white garment be a sign to you of your

Christian dignity.

With your family and friends to help you by word and example,

bring it unstained into eternal life.

The white garment symbolizes that the newly baptized person has realized Paul’s command to “put on Christ” (Galatians 3:27, CCC §1243), and recognizes the child’s new identity as a sharer in God’s own nature. The color white symbolizes that the Christian has been delivered from the dominion of darkness and transferred into the Kingdom of marvelous light (Colossians 1), and now wears the stola immortalitatis. She is now a Christian, a sharer in the divine nature, and has all the rights thereof: to participate fully in the sacramental and worship life of the Church and to benefit richly from the treasury of merit.

However, the new white garment does not just reflect a new identity, elevation, and bestowal of rights, but an imposition of duty: the duty to express this new identity by a morally upright life in accord with the Gospel. Pope Leo reminds baptized Christians that they need to recognize their dignity, and not return to their “former base condition by sinning. Bear in mind who is your head and of whose body you are a member.” The baptismal rite implores the new Christian to bring the garment “unstained” into eternal life.

The clothing with chasuble at a priestly ordination rite also has this twofold symbolism of both the bestowal of a new identity and an imposition of duties. Indeed, the priest is sacramentally configured to share in a new kind of way in the unique high priesthood of Christ. However, this new share comes with new obligations, which are given in the homily that the bishop offers to the ordinands. The baptismal identity is now lived out in and through the ministerial identity, especially pastoral care of the people of God. The ministerial priest lives out his holiness “under a new title and in new and different ways deriving from the sacrament of holy orders” (Pastores Dabo Vobis §19).

According to the prescribed homily of the ordination rite, the priest needs to let his teaching “be nourishment for the people of God,” with his new holiness of life being a “pleasing fragrance to Christ’s faithful, so that [he] may build up by word and example that house which is the Church of God.” He must exercise his ministry of sanctifying, and by his ministry “the spiritual sacrifice of the faithful will be made perfect.” In the language of Pastores Dabo Vobis, the priest brings to the people of God “the fullness of life and complete liberation” (§21). However, to carry this out well, he must “strive to put to death whatever is sinful within [him] and to walk in newness of life”—that is, to grow in personal holiness, which includes his exercise of pastoral care for the people of God (Ordination Rite).

The chasuble, the distinctively priestly garment, signifies both this new identity and the new duties that the ministerial priest takes on. This chasuble is placed over the alb—which is not a distinctively ministerial garment, but a baptismal one. The alb—the baptized identity—serves symbolically as a foundation for the new identity represented by the chasuble—the ministerial identity—which is laid on top.

It is worth noting that in both the case of the newly baptized infant and the newly ordained priest, another Christian places the new garment on, signifying that these new offices are gifts to be received rather than things to be taken. It also manifests the ecclesial, communal nature of both the baptismal and ordained priesthood, a reality whose symbolism is deepened through the lighted candle and the fraternal kiss of peace.

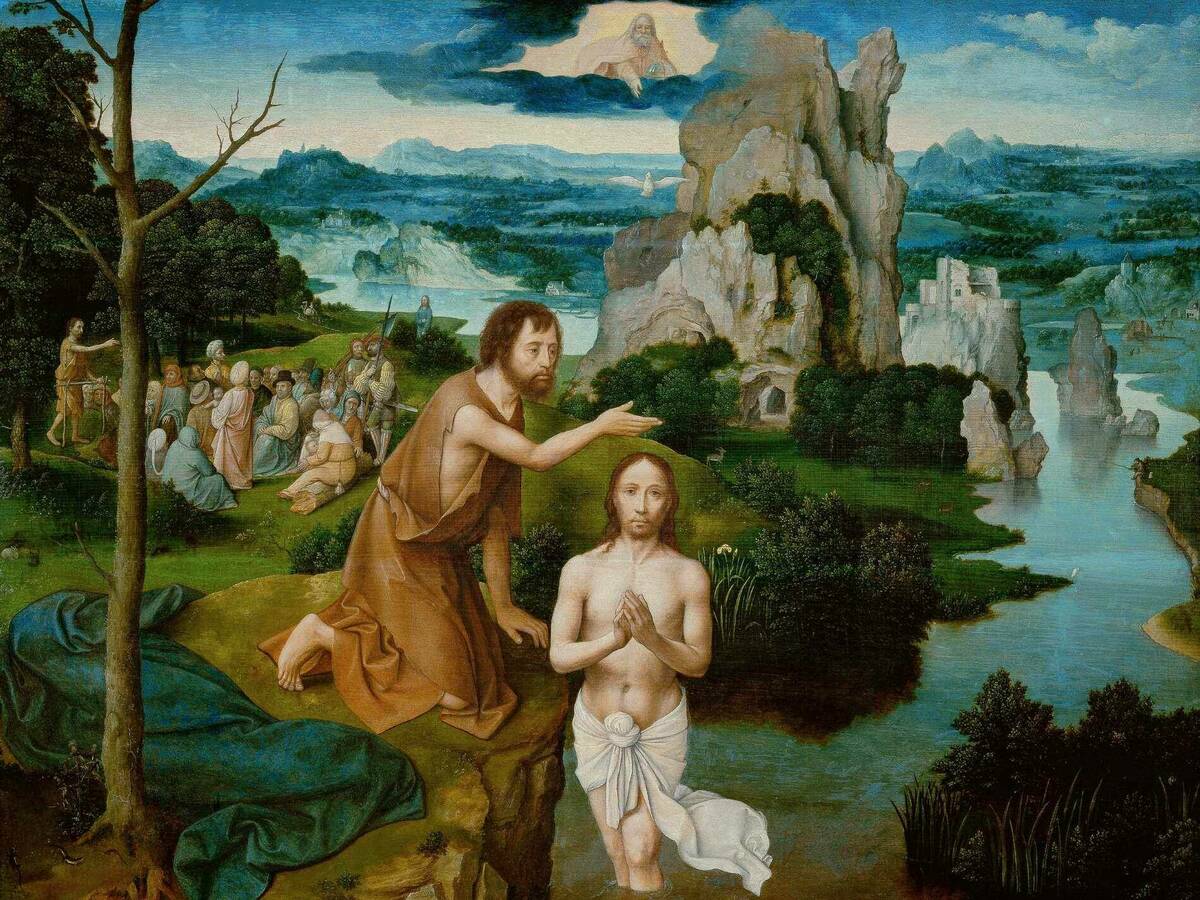

Anointing with Sacred Chrism

An anointing with sacred Chrism takes place in both liturgies. In the ordination rite, it takes place after the clothing with the chasuble. The baptismal rite calls for an anointing with Sacred Chrism immediately after the baptism by water. The minister of the sacrament prays:

Almighty God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,

has freed you from sin,

given you new birth by water and the Holy Spirit,

and joined you to his people.

He now anoints you with the Chrism of Salvation,

so that you may remain as a member of Christ, Priest, prophet, and king,

unto eternal life.

Then the ritual instructs: “Without saying anything, the celebrant anoints the child with sacred Chrism on the crown of his (her) head.” The Praenotanda explicitly connects this anointing with the baptized priesthood: “The celebration of the Sacrament . . . is completed, first by the anointing with Chrism, by which is signified the royal priesthood of the baptized and enrollment into the company of the People of God.”

While the Roman Catechism goes so far as to argue that chrism dates back to Christ himself, the Catechism of the Catholic Church is more restrained in saying it dates to “very early.” The early Christians (who were more generous with the application of chrism than the present Latin rite calls for—Cyril of Jerusalem describes anointing all of the sensory organs and the breast of the newly baptized), understood it as configuring one to Christ the priest, following in the tradition of Aaron.

This new union with Christ demanded a certain expectation of holiness, and the offering of the sacrifice of one’s life, and the sanctification of the world. The tangible and visible sign of anointing with Sacred Chrism was understood by St. Cyril and others to externally signify the sanctification by the “holy and life-giving Spirit” that transpires inside the soul.[3]

All priests offer sacrifice, and the baptized priest is to offer the sacrifice of his or her entire life to God the Father in pursuit of holiness, even to the point of martyrdom, to the point of “shedding one’s blood” in pursuit of Christ, and for the sanctification of the world. Short of the martyrdom of blood, baptized priests are to live a life of radical holiness and sacrifice, prioritizing the needs of others above themselves, sacrificing their desires through subordinating aside their baser passions in pursuit of the higher calling of God, and suffering under the martyrdom of charity. They present themselves as “a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God” (Rom 12:1). It is easy to find members of the royal priesthood of the baptized who are mothers or fathers living out the call to be “living sacrifices” in their perpetual nurture and care for their (especially young) children.

According to Sacrosanctum Concilium, the baptized also have a “right and obligation by reason of their Baptism” to a “full, conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy” (§14). The anointing after baptism signifies the new relation that the Christian is to have to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass—they are not to be passive bystanders who happen to be in a Church, but are to unite themselves to the ministerial priest, who invokes them to “pray, brothers and sisters, that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God the almighty Father.” The ministerial priest stands in persona Christi capitis to offer the Holy Sacrifice, but each of the faithful, in exercising their baptismal priesthood are to make the ministerial priest’s words their own as he repeats the words of our Savior.

The ministerial priest is reminded at the anointing of his ordination that his new life is for the sake of the Christian people. Rather than the liturgy being primarily for him, the ordination expresses the focus of his priesthood to be the sanctification of the Christian people:

The Lord Jesus Christ,

whom the Father anointed with the Holy Spirit and power,

guard and preserve you

that you may sanctify the Christian people

and offer sacrifices to God.

Then the priest’s hands are anointed. Whereas the anointing of the head at baptism synecdochically signifies the anointing of the entirety of the person, who is to offer himself as a living sacrifice, the priest’s hands are anointed, since these are the instruments of the exercise of his priesthood in the offering of the Eucharist and the words of absolution, although this anointing of the hands is also, in some measure, a synecdoche.

The ministerial priest must thus remember his anointing with chrism at both baptism and ordination in order to fully understand the nature and mystery of his own priesthood. The sacrifice of one’s life that is characteristic of ministerial priests nevertheless discovers its foundation in the baptized priest’s sacrifice of life, the subordination of unruly desires to the objective good, and the sacrifice of charity or blood for the sanctification of the world.

When a ministerial priest loses sight of his baptismal priesthood (and the concomitant truth that his ministerial priesthood is ordered towards the service of his own baptismal priesthood and that of all the lay faithful), he becomes preoccupied with his own needs, shaping the liturgy and his ecclesial office to be a platform for the expression of his own preferences, comforts, or self-aggrandizement.

Ecclesial Expression: The Handing On of a Lighted Candle and the Fraternal Kiss

The liturgies bestowing the baptismal or ministerial priesthood upon a person both express the ecclesial nature of the new office. Perhaps this is most pronounced in the corresponding rites of the handing on of a lighted candle in the baptismal liturgy, and the fraternal kiss of peace in the ordination ritual.

The handing on of a lighted candle is a sign that one enters into the Paschal Mystery as a member of the Mystical Body of Christ, rather than as an isolated individual. The minister takes the paschal candle and says, “Receive the light of Christ,” to “one member of the family (e.g., the father or godfather)” who “lights a candle for the child from the paschal candle.” The fellow viator of the newly baptized child lights the candle for the child from the source of all of Christian “lights,” Christ himself, represented in the paschal candle. The celebrant says,

Parents and godparents,

this light is entrusted to you to be kept burning brightly,

so that your child, enlightened by Christ,

may walk always as a child of the light

and persevering in the faith,

may run to meet the Lord when he comes

with all the Saints in the heavenly court.

The light—signifying the new life in Christ—is entrusted to the members of the Mystical Body closest to the child so that they can help the child live out her new vocation to Christian priestly holiness and offer the sacrifice of one’s life in accord with the truth of the Gospel. The baptized priesthood is not lived out in isolation, but rather as a member of the indefectibly holy Body of Christ.

The ordination ritual includes a similarly expressive ecclesial dimension following the ordination. The “fraternal kiss” is initiated by the bishop, who serves as the “visible source and foundation” of ecclesial unity in his diocese (Lumen Gentium §23). The ritual instructs that “the bishop gives the newly ordained the fraternal kiss, saying: ‘Peace be with you.’” The ritual continues, “Likewise, all the priests present, or at least some of them, give the fraternal kiss to the newly ordained.” The newly ordained priest has a new role in the body—the people of God—and he is welcomed into this new ordo presbyterorum by his fellow presbyters, whom he will serve alongside in the vineyard. It is particularly fitting that the fraternal kiss begins with the bishop, the shepherd, with whom the newly ordained priest must preserve communion, in order to promote the good of the flock.

During this fraternal kiss, the church recommends in particular the singing of Psalm 100 (99) with the antiphon, “You are my friends, says the Lord, / if you do what I command you.” This psalm includes one of the iconic expressions of the Church of God in Israel: “It is he that made us, and we are his; we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.” Both the handing on of the lighted candle and the fraternal kiss of peace express the ecclesial, fraternal nature of the office of priesthood—both baptismal and ministerial.

The Instruments of Priesthood: the Ephphatha Prayer and the Traditio Intrumentorum

Lumen Gentium describes Christ giving the baptized a share in “his priestly function of offering spiritual worship for the glory of God and the salvation of men” (§34). They carry out this activity by “consecrating the world itself to God.” In sanctifying the world, those sharing in the royal priesthood of the baptized have been given an “attractiveness in speech” so that they can evangelize and bring the light of Christ to the entirety of the world. Their priestly work of sanctifying involves bringing others to the source of all sanctification, Christ himself, fully present in his Church.

This work of the baptismal priesthood is carried out in the preaching of the good news to the world and the sanctification of that world. A key “instrument” for this work of the lay faithful is their lips, through which they go forth as “powerful proclaimer of a faith in things to be hoped for” (LG §35, see Hebrews 11:1). Those sharing in the baptismal priesthood use their lips to proclaim the faith, and this “instrument” is blessed in the Ephphatha prayer, where the newly baptized priest is opened to the Word of God, such that they can be transformed by it, and, in turn, sanctify the world by professing it. In the liturgy, the minster “touches the ears and mouth of the child, saying:”

May the Lord Jesus,

who made the deaf to hear and the mute to speak,

grant that you may soon receive his word with your ears and profess the faith with your lips,

to the glory and praise of God the Father.

The ministerial priest retains this mandate to preach the Gospel. At his ordination, however, he is given another instrument for his priesthood: that which pertains to the sacrifice of the Mass. The ministerial priest sanctifies the people of God first and foremost through the exercise of his priestly faculties in the sacrifice of the Mass. The instruments used for this exercise of the function is the chalice and paten given by the bishop to the ordinand. The chalice and paten are first presented to the bishop by members of the faithful who exercise their baptismal priesthood—providing the matter for the sacrifice, which will not just be the sacrifice of the minister, but their sacrifice also, which they are called to actively participate in. The Bishop states:

Receive the oblation of the holy people to be offered to God.

Understand what you will do,

imitate what you will celebrate,

and conform your life to the mystery of the Lord’s cross.

This ritual of the traditio instrumentorum was of such significance in the medieval period that some theologians speculated it was the essential matter for priestly ordination. While the Church has since clarified that the imposition of hands and consecratory prayer are the essential matter, the handing on of the instruments retains its weighty significance.

It is important for the ministerial priest to recall that he is offering the oblation “of the holy people.” He stands in personal Christi capitis, but the faithful are to unite their sacrifice to the priest’s and through his words and gestures offer a pleasing sacrifice to God. The ministerial priest is making this offering for those who participate in the royal priesthood of the baptized, and thus it is not his to tinker with—the liturgy belongs to the Church. He is also reminded that in offering this sacrifice, he is to conform his life to the mystery of the Lord’s cross—where Christ “loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2).

Conclusion

Lumen Gentium states very clearly that “the classes and duties of life are many, but holiness is one” (§41). This holiness is ultimately the holiness of the baptismal priesthood, the holiness of Christian life, of which ministerial priests are full participants and to which their whole life is to be ordered to serve. They serve this baptismal priesthood through pastoral charity and the sanctification of the flock.

It is wise for all ministerial priests to recall the words of St. Augustine, speaking to his flock, which can be read as a distinction between the baptized and ministerial priesthood: “What I am for you terrifies me’ what I am with you consoles me. For you I am a bishop; but with you I am a Christian. The former is a duty; the latter a grace. The former is a danger; the latter, salvation.”[4] If the ministerial priest receives the gift of salvation, it will be not in virtue of his ordination as such but in virtue of his cooperation with his baptismal call to holiness, which is now lived in and through his ministerial priesthood. His living out of the baptismal vocation includes his exercise of a specific manifestation of his baptismal priesthood—through pastoral charity and service to the people of God.

[1] Francis, “Letter to Participants in the Extraordinary General Assembly of the Italian Episcopal Conference” (8 November 2014), L’Osservatore Roman 258 (12 November 2014), 7.

[2] While the ritual does not use this term, it seems suitable to describe the following ritual actions as such, since they too add nothing to the validity of the liturgy.

[3] See St. Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures, Lecture 21.

[4] St. Augustine, Sermon 340, 1: PL 38, 1483; see also LG §30.